(A version of this review was published, in German, in the Swiss comics journal STRAPAZIN.)

Chris Gooch’s Under-Earth may not have been the best graphic novel published during the Global Pandemic (what would your nomination be?), but for my money it was a nearly perfect graphic novel for reading during the pandemic. As a tale set in a massive underground prison city where the only visible star is “rumoured to be a hole 600 meters up, just big enough to let in a glimmer of natural light … with no other purpose than to torment the populace,” Under-Earth embraces the reader in feelings of numbness, despair, anxiety, and even hope, in ways that resonated with so many of the ambivalent feelings we’ve all had over the last year.

Clocking in at nearly 600 pages, this book is a true graphic novel, though it actually reads more like a treatment for a film, and I mean that in a good way: I’d love to see what Tarkovsky or Kubrick could do with this source material. That said, Under-Earth works just beautifully as a comic book. Imagine Sammy Harkham, Gary Panter, and Katsuhiro Otomo sitting down to create a dystopian graphic novel and it might look something like Under-Earth. Though Gooch brings a particular degree of resolute empathy and hopefulness not seen often in those other cartoonists. Based on this book and his two prior (Bottled and Deep Breaths, neither of which is anything like Under-Earth), this young Australian is a talent to watch closely.

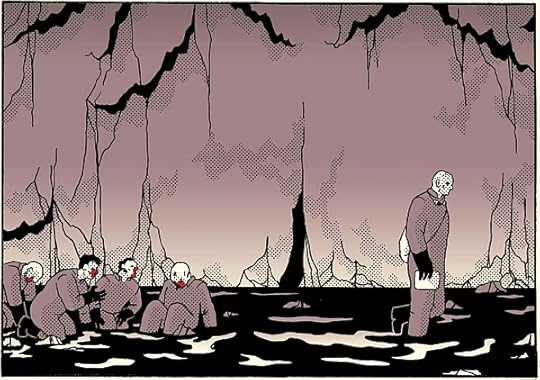

The story here is straightforward: a pair of female thieves (Ele and Zoe) and a mismatched pair of male prisoners living on the margins (Malcolm and Reece) struggle to survive in and take advantage of an oppressive and dehumanizing system that is definitively stacked against them. This simple story is deftly told via a series of interwoven parallel narratives and clever use of jump cuts and shifts in perspective, rendered in as engaging and skillful a drawing style as my Harkham-Panter-Otomo nod above suggests. The storytelling pulls the reader along quickly like the best Manga (many Western cartoonists in their 20’s seem to have internalized the grammar and syntax of Manga in an exciting and unselfconscious way) and the mostly monochromatic coloring (yellow, red, deep purple) powerfully conveys action, mood, and emotion.

While the main selling point of Under-Earth would seem to be its nightmare prison narrative (“Will they survive? Can they escape? What exists in the world outside this subterranean hell?”), what makes the book so special is its characterization. While the four main characters start off as “types”—the sullen loner; the nervous weakling; the tougher-than-you think ingénue; the surprisingly sentimental tough girl—we come to know each character relatively intimately, and at times their decisions and reactions surprise us. I read Under-Earth in one sitting, captivated by the plot; I read it again over the course of the next day, and the second time I came away with a real appreciation for Gooch’s storytelling skill and subtle sensitivity in character portrayal. I can’t wait to see what he does next.