And That's All?

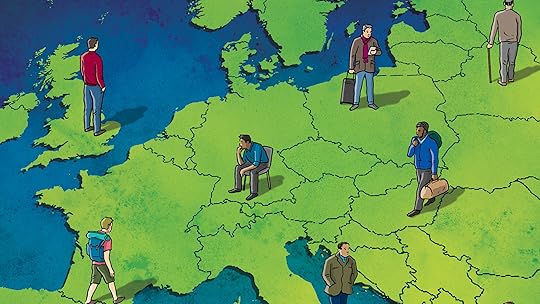

I considered many possibilities for the title of this review: first The Nine Ages of Man, then Holidays from Hell, then Losers. David Szalay's nine stories feature men at different stages of their lives, they are all set abroad, and they are uniformly depressing. Although there is only one small connection between them (the 73-year-old reired diplomat in the ninth story is the grandfather of the 17-year-old student in the first), the publisher's blurb suggests that they "aggregate into a picture of a single shared existence." And Szalay's title says that this is a composite portrait of what it is to be a man. If so, I'm not buying it. All these characters are losers, none more so than the pathetic Murray in the seventh story, fired from various jobs, a remittance man trying to survive in a dull village in Croatia, but dogged by failure with everything he tries. His is the longest story of the lot, dismally so, but at least it makes some of the others seem upbeat by comparison.

All the same, I stick by my description: Losers. Though, with the younger ones, perhaps not for ever. The sensitive young student in the first story, InterRailing round Europe with a friend who has very different ideas from his, will presumably come into his own as he grows up. And the French college dropout in the second story who goes alone on a package tour to a ramshackle hotel in Cyprus when his friend drops out, will surely not experience anything so horrendous again in his life. The semi-employed Hungarian ex-soldier in the third story, brought along as security for a high-priced call girl's visit to London, appears to have brawn rather than brains, but at least he shows himself to have a heart.

With the exception of the wretched Murray, the later characters, at the prime of their lives or in retirement, have all achieved a high measure of success. In the middle stories, we have a brilliant young medieval philologist, the deputy editor of a Copenhagen newspaper, and an international property developer. They are certainly not losers in the eyes of the world, but there is that matter of the heart…. The philologist behaves abominably when he learns his girlfriend is pregnant, but there is some possibility that he can atone. The editor flies to Spain to assure a high-ranking politician that his paper will be discreet in handling the news of his adulterous affair, but has he any intention of doing so? The developer has greater dreams than selling some jerry-built property in an Alpine village, but has he the courage to succeed?

The last two stories also feature outwardly successful men, but both in their different ways are contemplating the end of life. One is a Russian tycoon facing ruin on both the financial and personal fronts. The other (and to me the only really sympathetic character of the lot), is Sir Anthony Parson, a retired diplomat facing the end of his days and looking back on a life in which he has mainly acted a character not his own.

All the stories take place largely off the character's home turf. The protagonists are Belgian, Danish, English, French, Hungarian, Russian, and Scottish; the settings include Denmark, Germany, Italy, Slovakia, Spain, the French Alps, and a luxury yacht on the Mediterranean. This is a canny strategy on Szalay's part since many of us are tempted to behave differently when away from home. For the most part, though, this is not the glamorous Europe of the travel magazines. Prague is awash with tourists, the hotel in Cyprus is built on waste land a mile from the sea, the Alpine village has been blighted by gimcrack development, and the nearest town to Sir Anthony's Italian villa is famous only for its Museum of the Marshes (really).

So why do I not give this three or even two stars, if it presents such a dismal picture of masculine humanity? Mainly because David Szalay writes so well. Like his characters or not, you do get drawn into their stories. His descriptions are evocative and clear, but he also has a marvelous use of the ellipsis, short phrases that go nowhere definite but suggest much (an effect sometimes heightened by subtle uses of typography). In the same vein, he avoids neat endings; you are left with questions rather than answers; you can draw your own conclusions. In this general atmosphere of failure, I found myself looking for the few positive things I could find: a moment of unexpected companionship, a philosophical resignation, the possibility of change. And I have to say that I recognized most of the bad qualities in his masculine gallery from looking into the mirror of my own life at one time or another.

But I do not accept that this is All That Man Is. Hence my final title, itself a question: And That's All? And my emphatic answer: NO! However true Szalay is, I know we men can be so much more.