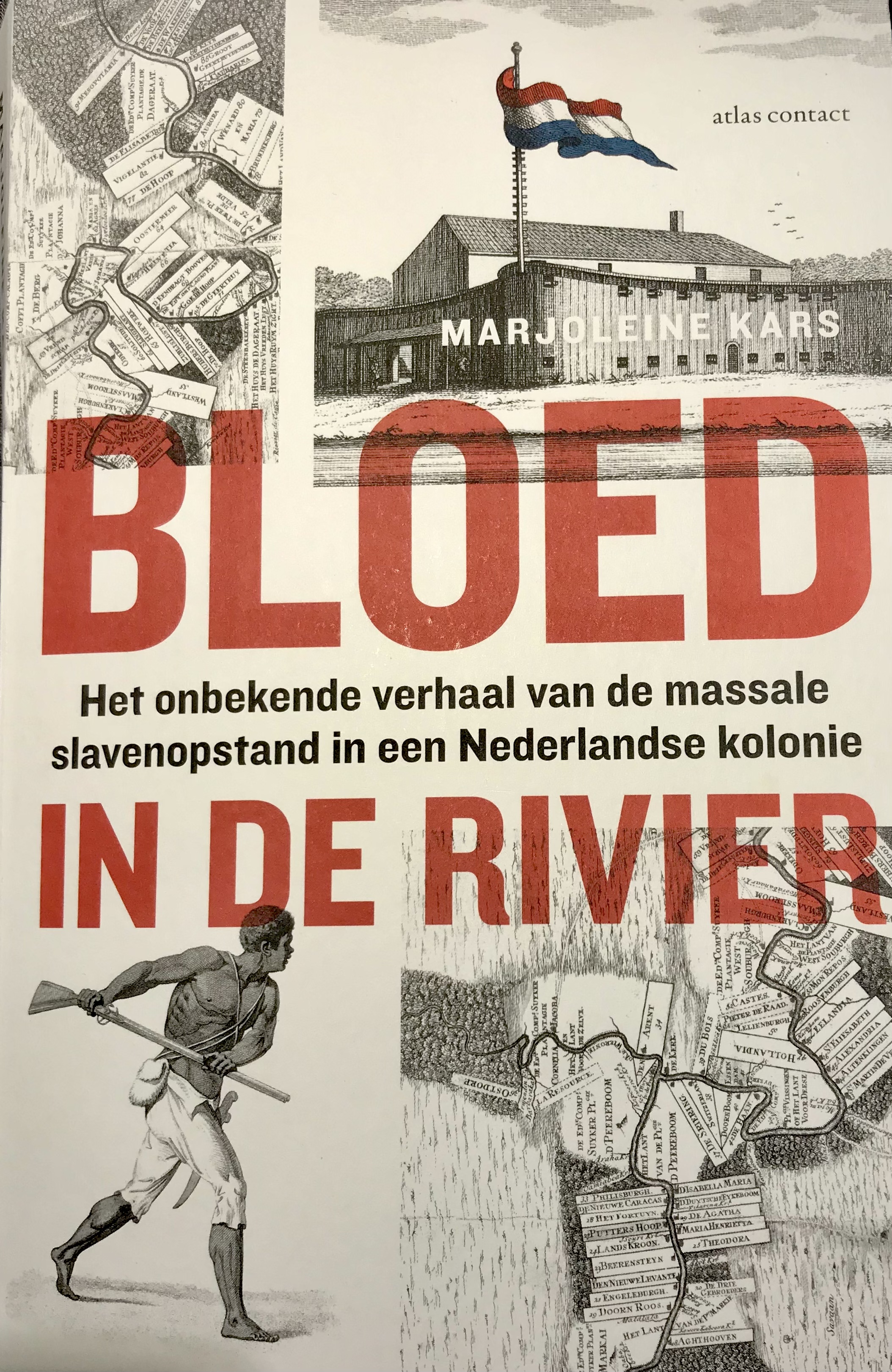

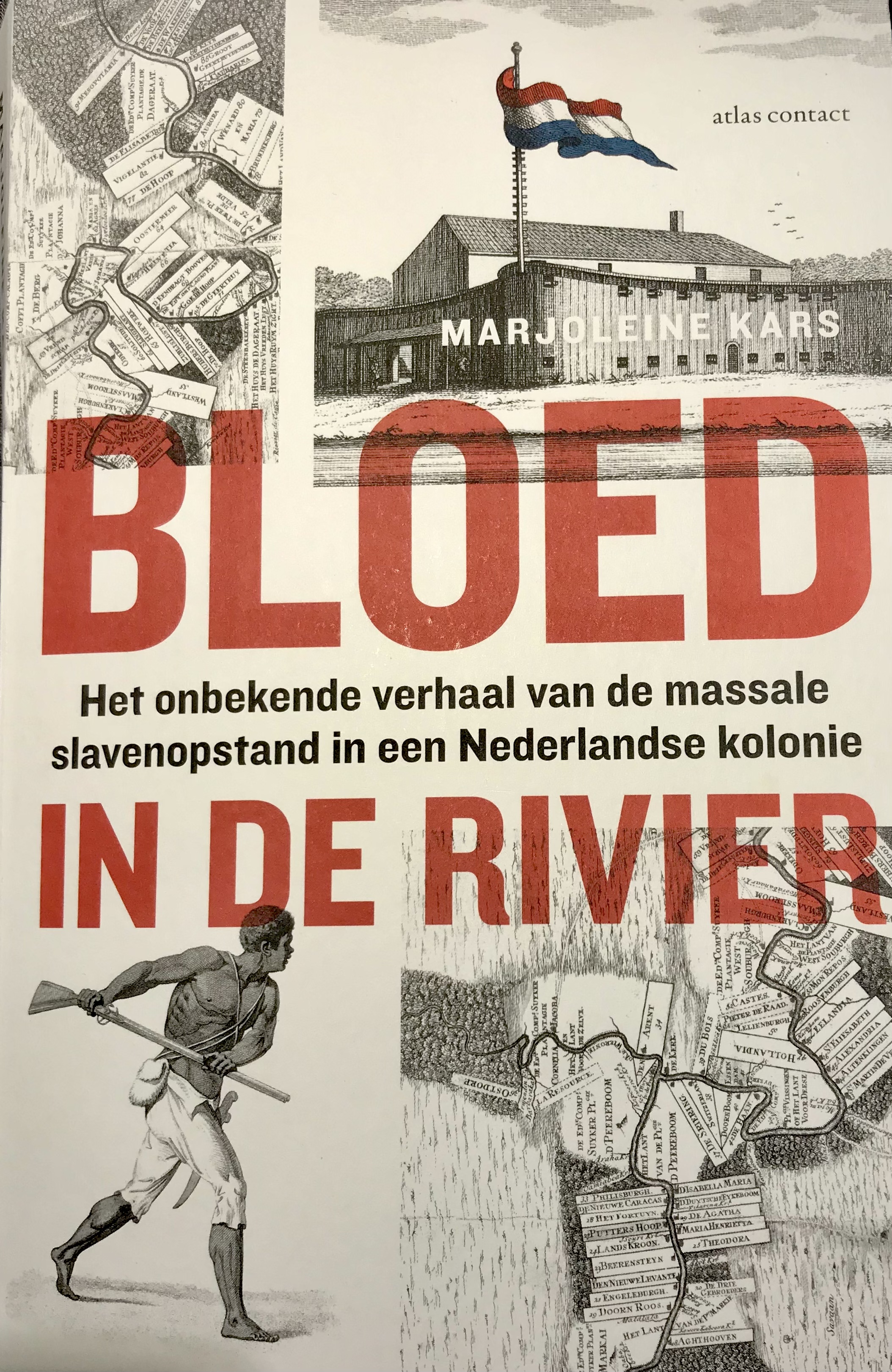

Kars got off to a great start in drawing on documents in the Dutch National Archives in the Hague, including the daily journal of the colonial governor, reams of European correspondence, 500 handwritten pages of slave interrogations and letters the rebelling ex-slaves had written to the Dutch authorities to write this book. Early in 1763, slaves in Berbice revolted. The subsequent rebellion lasted more than a year and involved nearly the entire enslaved population of about 5,000 people spread over 135 estates.

There was much I did not know about the Dutch colonies on the so-called wild coast of South America – an area between the mouth of the Orinoco River and the mouth of the Amazon. The plantations in today’s Guyana were held by the Dutch West India company, not by their government. It meant that decisions about managing the slaves, whether feeding, housing, clothing, or other requirements, were all made on strictly economic grounds. It meant funds were not unlimited. It slowed the response of the Dutch government to supply troops when it became evident that the violence could not easily be contained.

Company ownership also influenced the choices made after the rebellion when some planters unilaterally declared their slaves innocent and took them all back to work for the next planting season. One actually participated as a judge at the trials of the rebels. He didn’t argue with the governor’s request that his slaves be questioned by the court; he simply packed them all onto tent boats and took them home. When he felt he needed to be back at his plantation, he went there, putting all judicial procedures on hold until his return. Governor Van Hoogenheim knew that one planter in particular, Dell, was especially violent. Several slaves in the interrogations specifically accused him as a reason for the uprising. But the governor had no legal authority to hold him accountable beyond verbal warnings. When Dell returned to his plantation, he continued his brutal tactics. After the revolt, the colony never recovered economically under the Dutch. Fully one third of the plantations were destroyed. The company itself survived thanks only to huge loans from Dutch government.

Confronting the rebels, the Dutch faced a grueling experience as they struggle to fight their way through the impenetrable jungle. Mosquitoes, vampire bats, snakes, pirañas, poisonous plants, and other tropical hazards eroded their confidence and, in many instances, killed them. The heat was so unfamiliar to them that Dutch commanders actually ordered some units not to leave their bases.

Kars’ described in some detail the typical penalties meted out by Dutch justice. As with most European justice systems, the Dutch differentiated between the wealthy and prominent and the impoverished and lower class individuals. The system did not include trial by jury. Both the death penalty and corporal punishment were rare without a confession. Those accused could be tortured to secure confessions. If you confessed, you lost your right to appeal. Executions included hanging, the rack, and the stake. Particularly egregious cases could burn by “slow fire” where the blaze purposely was kept small so you died extremely slowly. Atta, the rebel leader throughout most of the year-long rebellion, died by slow fire.

Kars includes discussion of differentiation in treatment of those who killed “Christians” and those who killed only indigenous peoples and other slaves. The planters treated the former more harshly. She also notes that many rebels accused each other of eating their enemies. Investigation of these claims seemed to establish that the Ganga tribe had this practice in Africa and continued it in Berbice.

I didn’t know that Demerara sugar came from a region of today’s Guyana. The plantations of Demerara were located northwest of the area where the rebellion was underway. The leadership of Demerara provided some support and help to the leaders of Berbice in their efforts to control the slave revolt. First a colony of the Dutch West India Company and then of the Dutch state from 1792 to 1815, Demerara was merged with neighboring unit Essequibo under the British and became part of British Guiana in 1831. In 1966, Guyana achieved its independence.

Unfortunately, despite a strong historical narrative throughout the book, Kars falls flat a little at the end. She attempts to link the revolt in Guyana with slave, risings, slavery, and political movements in other parts of the world. Linkages should be made, I agree. Nevertheless, her description was rather disorganized and poorly edited - a disappointing end to an otherwise readable account of a little-known event.