What do you think?

Rate this book

442 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1967

A Romanian woman once sang me a phrase of folk music and I have since found it tens of times in different works from different composers of the past four hundred years. Indubitably: things do not begin; or they don’t begin when they are created. Or the world was created old.

It’ll be necessary that some of them have altercations and even become enemies, as is obvious, considering the close quarters they share, living in the same novel: characters destined to be permanent rivals, or those who are so only for a moment, must both conduct themselves as people who nevertheless share the same death, at the same place and time: the end of the book.

Author: I shouldn’t say to the reader, ‘Come into my novel,’ but rather save him from life indirectly. My quest is that every reader should enter my novel and lose himself in it; the novel will take him in, bewitch him, empty him out.

’The reader who won’t read my novel if he can’t know all of it first is my kind of reader, he’s an artist, because he who reads only seeking the final resolution is seeking what art should not provide, his interest is in the merely vital, not in a state of consciousness: the only artistic reader is the one who does not seek resolution.’For Macedonio, the true purpose behind any work of art is the creation of it, the mechanics that build and function within it. The President residing in La Novela – a character who may or may not be the author himself, reflects such ideals by having removed all paintings from his walls and in there place set up small art studios easels so as to be able to admire the creation of art as opposed to the final piece.

Like most people, I also came to Fernández through Borges, in the wistful question that ends his prose poem “The Witness:” “What will die with me when I die? What pathetic or fragile form will the world lose? The voice of Macedonio Fernández, the image of a roan horse on the vacant lot at Serrano and Charcas, a bar of sulphur in the drawer of a mahogany desk?”

The Novel That Begins

The Frustrated Novel (a manufacturing defect)

The Novel That Went Out In The Street, with all its characters, to write itself.

The Prologue-Novel, whose story plays out, concealed from the reader in prologues.

The Novel Written by its Characters.

The Inexpert Novel, which sets itself the task of killing off its “characters” separately, ignorant that creatures of literature always die together at the End of a reading.

The Novel in Stages

The Last Bad Novel–The First Good Novel–The Obligatory Novel.

The “for-all-of-us-artists-gifted-with-daydreams” Reader.

The “often-dreamed-of” Reader; The “who-the-authoer-dreams-is-reading-his-dreams” Reader.

The “who-the-art-of-writing-wants-to-be-real-more-than-merely-real-reader-of-dreams” Reader.

The “only-real-that-art-recognizes” reader of dreams.

The “less-real, he-who-dreams-the-dreams-of-the-other,-and-stronger-in-reality,-since-he-does-not-lose-it-although-they-won’t-let-him-dream-them-but-only-re-dream” Reader.

I believe I have identified the reader who addresses himself to me, and I have obtained hte proper adjectivalization of his entire being, after so much fragmentation and some false adjectives.

Real Characters:

Fragile Characters, owing to their vocation in life, because they believe they can be happy:

Nonexistent Characters (with presence):

Perfect Character, owing to a genuine vocation for being content to be a character:

End of the Chapter Character:

Absent Chapter Character, or Absence as character:

Smart, theoretical Character:

Thwarted Character, and Candidate for Character:

Unknown Character (the only celebrity appearing in the Novel).

Awaited Character:

Characters by absurdity:

Characters rejected ab intio

Never yet have I found the woman from whom I wanted children, except for this woman whom I love: for I love you, O Eternity!

For I love you, O Eternity.

—Nietzche’s Zarathustra, harking back to Diotima’s speech to Socrates in Plato’s Symposium.

It’s very subtle and patient work, getting quite of the self, disrupting interiors and identities. In all my writing I’ve only achieved eight or ten minutes in which two or three lines disrupted the stability, the unity of someone, even at times, I believe, disrupting the self-sameness of the reader. Nevertheless, I still believe that Literature does not exist, because it hasn’t dedicated itself solely to this Effect of dis-identification, the only thing that would justify its existence and that only Belarte can achieve. Perhaps Painting or Dance could also attempt it.

Space is unreal, the world has no magnitude, given that what we can encounter with our widest gaze, the plains and the sky, fit in our memories, that is, in an image.

…Duration is merely the sum of the changes that must occur…

6.4311 If by eternity is understood not endless temporal duration but timelessness, then he lives eternally who lives in the present.

Our life is endless in the way that our visual field is without limit.

(Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus)

Night is the beauty in which it pleased you to dress yesterday

All the characters are under obligation to dream of being, which is their proper way of being, inaccessible to living people, and the only genuine stuff of Art.

Ever since I’ve been an author I’ve looked on in envy at the audience there is for auto accidents. I sometimes dream that certain passages in the novel had such a throng of readers that they obstructed the progression of the plot, running the risk that the difficulties and catastrophes of the interior of the novel would appear in the forward, among mangled bodies.

Reader, I need you to breathe on this breathless page. Lean in more; all existence is so sad.

A hundred title-readers are calculated for each book reader; text-titles and cover-books do not mistake the reader; they are often brilliant Literature's only hope for a wide radius of influence, since these titles are not content with the modest title of cherished and secret Literature.There's a thin line between tongue-in-cheek discoursing and self-vindicating ramblings. One takes on what it knows to be quite the impossible task, but doesn't set itself up so highly in realms that it obviously has no real understanding of that it can no longer poke fun at itself and its efforts. The other seems to promise such, but eventually gets so bogged down in the kinds of tirades born out of preferring mail order catalogues and social intercourse with only the 'right' kinds of folks to the real world that it's not only impossible to take them seriously, but also impossible to find them entertaining. Perhaps I would have gotten a truer idea of how I would actually engage with this work if I had payed less attention to talk of 'proto-Borges' and more so to mentions of themes of suicide, but I doubt I had the self awareness for such when I added this work eight years ago. For Fernández, for all his metafictional blustering, has a bone to pick with various ideologies of his day, and the conclusions that he ends up drawing from both the texts considered cutting edge in his time and his personal experiences are so neurotypical in their tone that they're mostly irrelevant to my reading concerns and tedious otherwise. It's a shame, cause when he sticks to topics that he's not nearly so self-righteously judgmental on, such as the state of marketing and publication of literature, he's quite charming in a manner reminiscent of the best of de Assis. Beyond that, there's a fundamental level of dishonesty fueling his entire 'anti-novel' project here that would have been softened, if not completely done away with, if he had had the simple habit of honestly discoursing with certain people who cohabitated with him for literal decades. Considering how the work turned out, it's safe to say that those conversations never happened, and, given the circumstances, those would have been greater intellectual feats than any of pulling of ideas from William James, Cervantes, and Shakespeare that ended up occurring in their place.

When the world hadn't yet been created and there was only nothingness, God heard it said: it's all been written, it's all been said, it's all been done. "Maybe that's already been said, too," he perhaps replied out of the ancient, yawning Void. And he began.If you want in depth talk about the metafiction, or the influences, or Open Letter Books (a wonderful project that I'm keen on following regardless of this first experience with their work), there are plenty of positive reviews out there that cover such. I simply prefer being able to read experimental works without being constantly reminded how some folks vastly prefer being able to understand the fake rather than the real.

“We are a limitless dream and only a dream.

We cannot, therefore, have any idea

Of what not-dreaming may be.

Every existence, every time, is a sensation, and each one of us is only this, always and forever…

Only our eternity, an infinite dream identical to the present, is certain.”

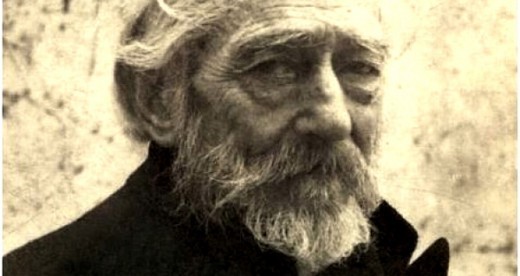

“The marks are not always intelligible or identifiable: they are ciphers. The only certainty is that Macedonio once held his living hands to these pages. It’s like laying one’s ear to a train track to listen for the vibrations of a train that passed fifty years ago. Microscopically, they are there–and knowing that is the thrill that keeps your ear pressed to the track.”

“The characters in this novel do not have physical bodies, organs or cosmos. Their communications are direct without words (which the author will have to invent and attribute); they are nothing but direct psychism operating from consciousness to consciousness. The nearness of one consciousness might feel to another is not distanced, but consciousness causation between consciousnesses. The characters must live on ideas and psychic states- they are psychic individuals. This wordless novel seeks to dissolve the supposed causality that the cosmos exercise over consciousness that, if without tigers, that we could feel a tiger wound and maul us, we could feel what we feel without a cosmos's color, sounds, odors. There is an original series of phenomena and conscious phenomenology."Got it.

“When physicists constructed their visual, tactile world out of atoms, they believed that they could say something, understand something, with the invisible and the impalpable in the same way. They unconcernedly invented the apparition of consciousness and the heart of these precious recombinations of the insensible and the unconscious: matter…

On the other hand, they found it senseless that idealism should deny time, space, and the self matter. That it should affirm the sensible State, my current sensory state, as its only object of intellection. This is how I name and define being eternally: Auto-existing. The eternal mystical and the intellection, which is not to say the category "being" is not fleeting and cannot be lost a time without world… A not-being of being is an impossible notion…

When I want to think of nothing, the image arise in my mind that can capture this thought if an image arises. I'm thinking of something and not nothing. If there isn't an image then I'm not thinking. It's true that we have the word nothing which alludes to something. It's a conditioned-negation or a partial conditioned existence…

Space is unreal. The world has no magnitude. Given that we can encounter with our widest gaze, the planes and sky fit in our memories. That is in an image. Thus it shows that one the exterior is not intrinsically extensive too. The mind psyche, consciousness, soul sensibility all essentially synonyms for subjectivity- has no extension, position, or station anywhere; that immensity, the cosmos, is therefore a point or better the autonomous involuntary Image, the contingent and spontaneous that we face with our will. In other words, everything that exists is an image. Some voluntary, others are involuntary– dreams and reality intermingling and giving rise to the same emotions and acts when they are equally vivid…

An object that we call distance can offer us a tactile sensation is an effect of space and its only reality. Likewise, with regard to time, it's reality resides in its effect: that a waiting is required which is to say a series of events so that there's a desired or feared outcome after one of those changes or states of things which we call the present.

Size (space) and duration (time) are not real but inferences with respect to the effect of the muscular work of transposition or the mental work of hope. Uncertainty, desire, duration, is merely the sum of the changes that must occur that must make themselves actual before another change happens; this before and this make itself actual are not temporal implications which would be tautological in this case but psychological correlatives: so The Actual is a state when the feeling- fear or desire- which is tied to it culminates in an insensibility: the fear of something as fear is naturally always actual or present. But the represented or perceived scene is only real when the fear reaches its limit…

I've said all this to establish the nothingness of time and space. These are abstractions which can only tell us what happens in terms of representations of scenes or events which in perception or reality bring us pain or pleasure which nevertheless are given in our minds several times sometimes giving rise to emotion and drives…This is the metaphysical certainty of my novel.”

“Perhaps some readers will find the much-vaunted Conquest of Buenos Aires by Beauty and Mystery to be less than lucid…If the author had made this chapter robust and gracious, he would have misrepresented the psychology of this action. For the rest, I will satisfy my incredulous and clever reader by confessing that the chapter is simply the work of a dried-up writer, who can do no more.”

“When life has for us an Eterna in whom all beauty finds expression, heartbeat, breath; to look towards art is like using a flashlight during the day…”

“I, who once upon a time imagined himself a man of complete good fortune, a man who elbowed his way through the multitude shouting Make way for a happy man!...”

“I can't give the anxious young person what he longs for– a certain understanding or power to achieve an ambition or a steady, secure direction in the darkness of being nothing concrete, just a sign in the sky, a tree in Africa, a strange affinity a turnstone a shadow profile that raising or retaining itself in the mind will signify to him that the act or intuition that he had in his mind. The moment he found it must continue on and is in fact would let him to the attainment of this desire, but I can send him down the path of such promising thoughts so ripe with total possibility that is eternity so heady with mystery that they will create for him an interior world so strong that no reality can have the power of sadness or impossibility or limitation for him that it is over. Someone who hasn't managed to construct thought fascinations to accompany him always. We can all cultivate this constant and powerful daydream that does the sharpness of an adverse reality. Religions, patriotism, humanism all do this in some way.”

“Here an elegant praying mantis has paused in front of my manuscript, undecided as to whether he would like to enter the novel.”

“We feel the emptiness of the world of the geometrical and physical presentation of things of the universe and the fullness and unique certainty of passion essential being without plurality. You'll smile as if spellbound by this void from a window that seems to look over an immense and immovable external reality that quickly reduces to a point. If you think for a moment, how the image of a scene you dream or imagine when you think yourself awake at night might contain the entire world and nevertheless it fits in your mind or Spirit if you like and the vibration of an imperceptible molecule of gray matter. As physiologists say, if, having taken in a panoramic view of the sun, earth, sky Forest River seas, river banks buildings later, you'll think or dream that you have exactly the same immense image closed in a point of your mind of your soul, or if you like in a microscopic nervous cell in your brain. Moreover, the same gray matter and the entire brand is an image in your mind since you wouldn't know it existed if it weren't for the images you have of its form, color division sketches, views and your images of contact temperature etc…This extension is what creates the illusion of plurality that isn't applicable to the only reality of being sensibility”

“Sweetheart’s innocent and sensual curves one could see Buenos Aires gleaming–that supreme city prowling through the shadows of the limitless land living in the darkness without destiny like an ocean liner illuminated in the vast darkness of the sea whose hearted cleaves; both live directionless and a fullness of the present. When one lives historically, there's nowhere for passion to go. This is the progress of humanity, which is the emphasis of History. Once one has been experienced and The Passion of the present progress and the future become pointless, the depraved notion of progress exists only in historical writing, not within any heart. Passion does not think of situation or time. Comparatively, each lives the same present continuum, the insatiable notion of progress is always empty. Always nothing.”

“Either art has nothing to do with reality or it's more than that. That's the only way it can be real, just as elements of reality are not copies of one another. All artistic realism seems to arise from the coincidence that there are reflective surfaces in the world. Therefore, literature was invented by copyists. What is called art looks more like the work of a mirror salesman driven to obsession who insinuates himself into people's houses, pressuring them to put his mission into action with mirrors, not things”

“Macedonio is metaphysics. Is literature. Whoever preceded him might shine in history, but they were all rough drafts of Macedonio.”