What do you think?

Rate this book

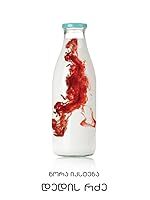

244 pages, Paperback

First published March 1, 2015

Motina pažvelgė į mus visus tokius skausmo persmelktu žvilgsniu, kad man pasidarė gėda savo netramdomo kumelaitės džiaugsmo. (p. 126)

Prie mūsų namų jis mane pirmiausia pabučiavo į skruostą, tada savo lūpomis apėmė manąsias, bet aš laikiau jas tvirtai suspaustas.

Tai buvo mano pirmasis bučinys. (p. 127)

Dvi raudonos juostos ir viena balta, pasakė patėvis, braukdamas pirštu per fotografiją. Mes turėjom savo valstybę ir savo vėliavą.

Dabar ir man ištryško ašaros, nes taip buvo sakiusi ir motina. (p. 136)

Apie motiną, kuri gyveno kaimo užkampyje, nes nenorėjo gyventi dviejų gyvenimų, nenorėjo nė to vieno, kuriame ji jautėsi tokia pat paniekinta kaip anksčiau Latvija. (p. 137)

Stotyje mane pasitiko Jesė. Jos veide akivaizdžiai atsispindėjo išgyvenimai. (p. 137)

Aš nekenčiau mažo, storo vojenruko visa širdimi. Ilgainiui mano vaizduotėje jis tapo visos šios paralelinio gyvenimo košės pagrindiniu kaltininku. Atgrasia, gličia rupūže, įsiropštusia į mūsų vandens lelijų tvenkinį, surijusia visus taikius laumžirgius, kuri tupėjo ant lapo ir kurkė, ir vis labiau pampo, ir visiems tą rūpužę tekdavo nuryti. (p. 142)

Aš buvau taip pabūgusi jo nuožmumo, kad drebėjau ir tylėjau. (p. 154)

At first glance this novel depicts a troubled mother-daughter relationship set in the Soviet-ruled Baltics between 1969 and 1989. Yet just beneath the surface lies something far more positive: the story of three generations of women, and the importance of a grandmother in giving her granddaughter what her daughter is unable to provide – love, and the desire for life.

This is classic Peirene Press: a short, intense novel that seems to contain more than is possible in 140-odd pages. Set in the 1970s and 80s in the Soviet-controlled Baltics, and telling the story of three generations of women, Soviet Milk may be the first Latvian novel you’ve read; we hope there is more to come.Throughout my childhood the smell of medicine and disinfectant replaced the fragrance of mother’s milk.

Peirene Press takes its name from a Greek nymph who turned into a water spring. The poets of Corinth discovered the Peirene source and, for centuries, they drank this water to receive inspiration.The idea of metamorphosis fits the art of translation beautifully. To turn a foreign book into an enjoyable English read involves careful attention to detail.Nora Ikstena's Mātes piens published in 2015, was indeed a bestseller in the Baltics and tells the story of three generations of a family centred around Riga - which I will try to refer to as the grandmother, mother and daughter in this review.

Peirene specializes in contemporary European novellas and short novels in English translation. All our books are best-sellers and/or award-winners in their own countries. We only publish books of less than 200 pages that can be read in the same time it takes to watch a film.