#Read 1992-1996

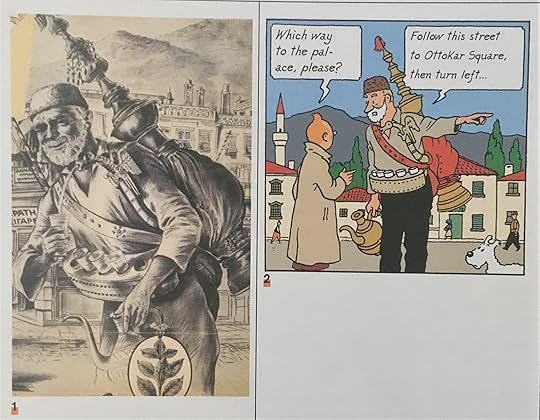

January 1994—Christmas vacations were just about to fold, and the winter air still carried the festive cheer of the season. For me, the holidays had always been a mixture of schoolwork, family gatherings, and the quiet indulgence of reading. That year, however, the end of the vacation brought an unexpected delight: my uncle, a colleague of my mother, gifted me a copy of Tintin #8: King Ottokar's Sceptre by Hergé.

I remember the crispness of the pages, the bold cover art depicting Tintin confronting danger, and the thrill of holding a story I had been anticipating almost as much as my schoolbooks.

Receiving this comic felt like a bridge between the ordinary and the extraordinary. Winter afternoons in my hometown were often quiet and introspective, but Tintin’s adventures promised excitement, mystery, and the subtle lessons embedded in clever detective work.

Hergé’s meticulous artistry immediately drew me in. The illustrations were precise yet vibrant, filled with detail that made every panel an invitation to linger. Unlike ordinary books, where the narrative might drift slowly, Tintin’s story demanded attention—every frame a clue, every character a potential source of surprise.

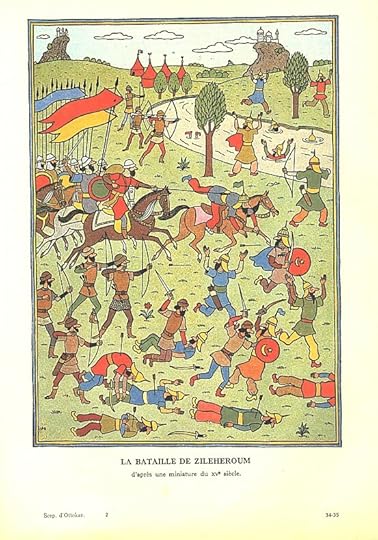

King Ottokar's Sceptre opens with Tintin uncovering a plot to overthrow the monarchy of the fictional kingdom of Syldavia. A stolen royal sceptre becomes the focal point of an intricate conspiracy, and Tintin, as always, is propelled into a race against time. I remember being captivated by the combination of suspense, politics, and adventure.

Hergé’s skill lies not just in creating action, but in making the reader feel the stakes: the sceptre is not merely a symbol of power, but a tangible object whose theft threatens a nation. Even as a child, I felt the tension and urgency, my heart racing alongside Tintin as he navigated hidden corridors, suspicious characters, and sudden confrontations.

Snowy’s wit and loyalty added charm and humour, while Captain Haddock’s fiery temperament provided both comic relief and emotional depth. Haddock’s exaggerated exclamations and bluster contrasted beautifully with Tintin’s calm intelligence and careful reasoning, creating a balance that made the story both thrilling and engaging.

As I turned the pages, I was drawn not just into the plot, but into the rhythm of Hergé’s storytelling: suspense punctuated by humour, danger softened by ingenuity, and heroism tempered with humanity.

Reading this comic in the quiet of a post-holiday afternoon made the experience even more immersive. While the celebrations outside were winding down, I was swept away into Syldavia’s palaces, forests, and secret hideouts. Tintin’s courage, attention to detail, and relentless curiosity inspired me in subtle ways.

I began to notice that adventures did not always need to be physical; they could be mental, intellectual, and moral as well. The story encouraged me to value observation, patience, and creative problem-solving, all while being entertained by a narrative that moved with precision and flair.

Looking back, this gift was formative. It reinforced my growing love for Tintin’s world and introduced me to stories where suspense, logic, and human complexity coexisted harmoniously.

The comic’s narrative structure, its careful pacing, and its balance of tension and humour taught me to appreciate how storytelling could shape perception and imagination. It was a lesson that extended beyond the pages: that life itself could hold mysteries, challenges, and moments of discovery, if approached with curiosity and courage.

Even now, I recall that winter afternoon vividly. The thrill of opening King Ottokar’s Sceptre, the quiet concentration as I traced each panel, and the exhilaration of following Tintin through political intrigue and danger remain etched in my memory.

That gift from my uncle, small yet significant, became more than a comic; it was a key to a world of adventure and imagination, a companion in my childhood, and a benchmark for the stories that would continue to shape my love for literature.