What do you think?

Rate this book

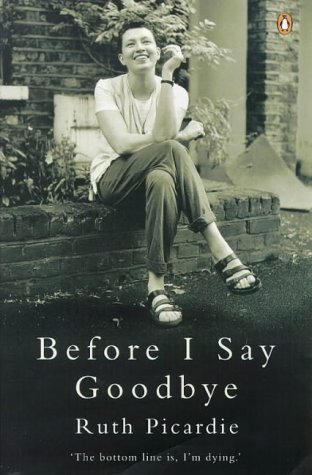

128 pages, Paperback

First published May 7, 1998

“You ram a non-organic carrot up the arse of the next person who advises you to start drinking homeopathic frogs’ urine.”

“Worse than the God botherers, though, are the road accident rubber-neckers, who seem to find terminal illness exciting, the secular Samaritans looking for glory.”

(from Seaton’s epilogue) “Like Ruth, I have no religion, but I can more easily understand than ever the appeal of the idea of an afterlife. Not that it doesn’t still seem a magnificent fiction, but without it it is so hard to imagine where all that dynamism, all that spirit, energy and force of personality that was Ruth could have gone. Can it be that it simply leaches away entropically?” [I have felt much the same thing since my brother-in-law’s death.]