What do you think?

Rate this book

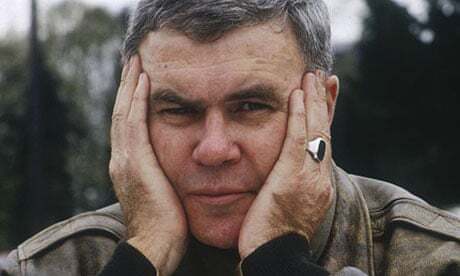

The London Times called Raymond Carver "the American Chekhov." The beloved, mischievous, but more modest short-story writer and poet thought of himself as "a lucky man" whose renunciation of alcohol allowed him to live "ten years longer than I or anyone expected."

In that last decade, Carver became the leading figure in a resurgence of the short story. Readers embraced his precise, sad, often funny and poignant tales of ordinary people and their troubles: poverty, drunkenness, embittered marriages, difficulties brought on by neglect rather than intent. Since Carver died in 1988 at age fifty, his legacy has been mythologized by admirers and tainted by controversy over a zealous editor’s shaping of his first two story collections.

Carol Sklenicka penetrates the myths and controversies. Her decade-long search of archives across the United States and her extensive interviews with Carver’s relatives, friends, and colleagues have enabled her to write the definitive story of the iconic literary figure. Laced with the voices of people who knew Carver intimately, her biography offers a fresh appreciation of his work and an unbiased, vivid portrait of the writer.

592 pages, Hardcover

First published September 8, 2009

The rapist. What moment of his life would you pick to tell about While he's having a cup of coffee at Howard Johnson's? Perhaps he eats a clam roll. I myself like clam rolls but I have more than a clam roll in common with the rapist. What have I ever wanted to take? When have I ever wanted to scare and terrify? If you will look around you with eyes stripped you will hear voices calling from the crowd. Each has his own love song. Each has a moment of violence. Each has a moment of despair.Middlebrook's biography of Sexton doesn't diminish her, it enhances us, in the act of reading it -- it helps us hear her love song, feel her moments of violence and despair, and understand our own. Reading this biography of Carver had the opposite effect.

As someone who has been moved by Carver's short stories, it was fascinating to read about what or who inspired them and how the stories affected those close to him. To give one example, Cathedral was inspired by the visit to their home of Jerry Carriveau, an old friend of Carver's second wife, Tess Gallagher. He was blind and Carver was apparently expecting to meet a man wimpy and withdrawn but was confounded when he turned out to be feisty. Some years later, Tess also wrote a story inspired by Carriveau. It was slated for publication in a collection but her publisher suggested it was too close to Carver's already well-known Cathedral for readers not to notice. Gallagher became angry at this and protested that Raymond didn't have a right to that story as Carriveau was Gallagher's friend, not Carver's.

For an aspiring writer, there is a lot to learn from in Sklenicka's biography of Carver. Simply noting the names of Carver's friends opens up a whole milieu of late-20th century American writers for one to read and learn from. And one can learn not only from their work, but also the lives lived by them. In Carver's case, his alcoholism had a profound effect on his relationships, a lot of which he drew inspiration from in his bleaker stories. When one compares Carver's work as an alcoholic with his work in sobriety, one wonders if the price he paid for his inspiration was too high. (One should not interpret from this that Carver became an alcoholic to find inspiration). On the other hand, however, he arguably could not have written his masterful later works without the wisdom and discipline he gained from his recovery.