What do you think?

Rate this book

408 pages, Paperback

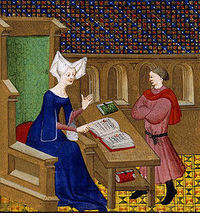

First published January 1, 1405

[A]s for the point you mention that these men attack women for the sake of the common good, I can show you that it has never been a question of this. And here is the reason: the common good of a city or land or any community of people is nothing other than the profit or general good in which all members, women as well as men, participate and take part. But whatever is done with the intention of benefiting some and not others is a matter of private and not public welfare...For they never address women nor warn them against men's traps even though it is certain that men frequently deceive women with their fast tricks and duplicity.I found this work less useful than other women in the past would have if access too it had not been largely denied to them a million times over, which sums up the nature of the beast when it comes to historical spans of institutionalized hatred that go into the building of the master's house. More than six centuries have passed since this perceptive work first came to light, six centuries that should have been filled with translation upon translation upon commentary upon criticism upon field of work upon movement upon meaning upon revolution, and instead we have a "modern" English translation at the tail end of the 20th century, between it and the first English translation in 1521 a vague and menacing blank. Simply compare this open maw of a history to the work-referenced Boccaccio or Dante or other contemporaneous male writers and you have an accretion that has grown nigh incontestable through sheer weight of influence and progeny and calcification into what is treated in this day and age as normal and viable and legit. Those myriad decades of wealth of growth were stolen from The Book of the City of Ladies by a little willful ignorance here, a little socially encouraged bad faith there, etc, etc, etc, and suddenly five centuries have passed and the patriarchy reigns with the certainty that none of its deconstruction will surface from the 14th and 15th centuries. Alas, for all the time lost to those who fought to make it seem as such.

A]fter a father and mother have made gods out of their sons and the sons are grown and have become rich and affluent—either because of their father's own efforts or because he had them learn some skill or trade or even by some good fortune—and the father has become poor and ruined through misfortune, they despise him and are annoyed and ashamed when they see him. But if the father is rich, they only wish for his death so that they can inherit his wealth.Pizan's work reflects the best and worst of its times, combining keen observation and deflation of hypocrisy and socially normalized marginalization along artificial constraints of gender via the weight of slander and absolutism with antiblackness, antisemitism, and blinkered centricity in the realms of sexuality, religion, history, and gender roles. The fact that the commentary is coming to prominence now rather than during the 16th or 17th or 18th centuries, however, is a symptom of the complex Pizan was fighting with every stroke of her pen, and the multigeneration gap happens because those who would've slowly but surely developed the text along more complicatedly inclusive lines were forbidden to read, or forbidden to learn, or forbidden to learn French, or forbidden to travel, or forbidden to travel alone, or forbidden to work, or forbidden to learn French, or forbidden to learn the classically complicated version of French Pizan lovingly renders, or forbidden to meet and greet and write their these paper on such ancient travail, etc, etc,etc, or were caused by any number of small obstacles to become exhausted by the effort of surmounting a system all by themselves and fall into complacency. The miraculous tragedy and tragic miracle is that, despite the last, thankfully brief, section that sounds like it came straight out of my Lives of Holy Women lecture, Pizan's words still point out the work that still needs doing, as six hundred years later the same slag is being spilled from the same lips and fists and rapes that rely on the combined powers of an erased history and a terrorist present to ensure the next Pizan will be lost for even longer to the eyes and arms of her like-minded audience. Complacency prevented Pizan's text from a natural continuation of development in the cultural limelight in which she belonged, and complacency damns and will damn others so long as the farce of obfuscation functioning today continues to present itself as normal.

Are the men who accuse women of so much changeableness and inconstancy themselves so unwavering that change for them lies outside the realm of custom or common occurrence? Of course, if they themselves are not that firm, then it is truly despicable for them to accuse others of their own vice or to demand a virtue which they do not themselves know how to practice.

Women are usually kept in such financial straits that they guard the little that they can have, knowing they can recover this only with the greatest pain. So some people consider women greedy because some women have foolish husbands, great wastrels of property and gluttons, and the poor women....are unable to refrain from speaking to their husbands and from urging them to spend less.Reading Pizan reminds me of all the work I have left to do. For every confident declarer of the nonentity of works, or even existences, of a certain demographic in a certain period, there is excavation to undertake and analysis to be done and acknowledgement to be generated, for nothing that has survived between one time and now did so out of sheer luck, more so if it has been suppressed via the efforts of the Powers That Be. Pizan's not the oldest of the works I've tackled and/or have yet to tackle, and she's also rather overly familiar, what with the whiteness and the wealth and the superficially heterosexual romantics. She does, however, offer a powerful cornerstone to build off of, which can be demonstrated simply by the Wiki page devoted to collating hyperlinks to all the historical and religious figures of women mentioned throughout the pages of this work. Parts of the tract have become stale and atrophies, but what remains applicable is so to the point of pain, for one always prefers that the sadists of yesteryear had been annihilated through sheer mass acknowledgement of fellow humanity. Christianity, or individual good intent, obviously isn't enough. What will be so remains to be seen, so long as there are readers willing to put the effort into seeing.

[I]t is very true that many foolish men have claimed [that it is bad for women to be educated] because it displeased them that women knew more than they did.

Certainly that man is servile who seeks to rule others but does not know how to rule himself. Woe to him who is overly concerned with having his stomach full of delicacies and takes no care for the famished; woe to him who wishes to be warm but fails to warm or clothe those dying of cold; woe to him who wants to rest and makes others work; woe to him who claims everything is his which he has received from God; woe to him who desires that everyone do him good and who does evil to all.