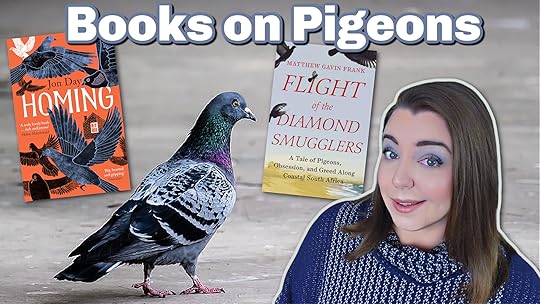

A couple nights ago, I finished reading "Flight of the Diamond Smugglers: A Tale of Pigeons, Obsession, and Greed Along Coastal South Africa" by Matthew Gavin Frank, a book that is part Homeric odyssey/part memoir/part contemplation on loss and grief. It's the sort of story that defies categorization, refuses to be pinned down. Like its titular diamond-smuggling avians, the pages fly off in wild pursuit of mysterious destinations, guided only by a kind of inner mytho-magnetic GPS system.

On the surface, "Flight of the Diamond Smugglers" is a historical and contemporary exploration of the ruthless De Beers diamond industry in South Africa, from infancy to violent conglomerate monstrosity. Yet, the book begins with Frank and his wife, Louisa, huddled on the edge of the Big Hole, "a gaping open-pit and underground diamond mine that was active from 1871 to 1914 . . . a man-made Grand Canyon." It is into this abyss that they empty a thermos containing the ashes of a lost child. Their sixth miscarriage. Frank recites Kaddish, and his wife whispers "Amen," as this tiny ghost swirls to the bottom of the hole.

From this ceremony, Frank launches into a narrative that spans the wasted coasts of South Africa, to Orpheus and the Underworld, to Krishna's cursed Koh-i-Noor diamond. It's a ride that takes wild turns. Isaac Newton and a wooden pigeon. Middle school Champagne Snowball dance and midnight meeting with a security demigod. Just when you think you see the destination ahead, "Flight of the Diamond Smugglers" finds an updraft or trade wind, and you go sailing into another gleaming facet or bottomless mine.

Stitching the book together, like a recurring motif in a symphony, are lyrical "Bartholomew Variations," Frank meditating on a particular diamond smuggling pigeon (Bartholomew) owned by a young mine worker (Msizi). The veins of these small sections carry the blood of the book to its heart. Through Msizi and his bird, Frank is able to humanize a story that, most of the time, seems inhuman, even otherworldly. And, by doing this, he transforms the book into something personal, alive, heartbreaking.

Matthew Gavin Frank is a master of juxtaposition, throwing all of these disparate elements--grief and greed, desperation and diamonds--into a tale that, ultimately, ends the way all stories about carrier pigeons end. With another long flight, another winding journey, through a dung-beetle night, toward a distant, waiting home.

Book passage on this trip. You won't be disappointed.