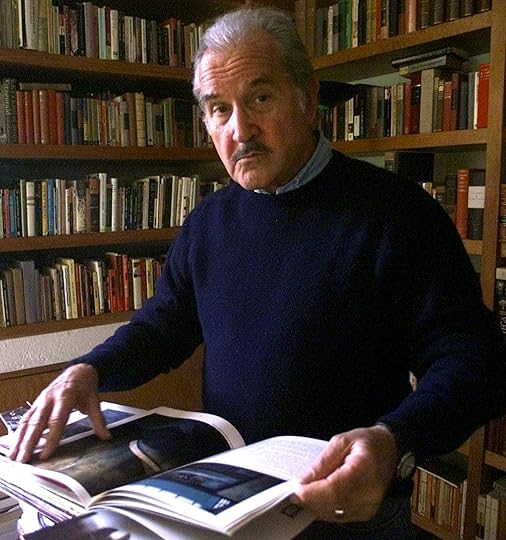

An old Anglo man in Mexico, amidst the turbulence of that country’s revolutionary period of 1910-20, might ordinarily not draw much attention. Yet in Carlos Fuentes’s 1985 novel El gringo viejo (The Old Gringo), the old man is not just any old man, and his journey across the Rio Grande has everything to do with reckonings facing both Mexico and the United States of America.

Fuentes, the son of diplomats who served in many nations of Latin America, later said that his residence in a variety of countries throughout the region gave him something of an insider-outsider’s perspective on his home nation of Mexico. The winner of prestigious literary awards like the Miguel de Cervantes Prize (given for lifetime achievement in Spanish-language literature), Fuentes is a careful observer of his society and a perceptive student of human character – and his interest in physical borders and cultural boundaries comes through strongly in The Old Gringo.

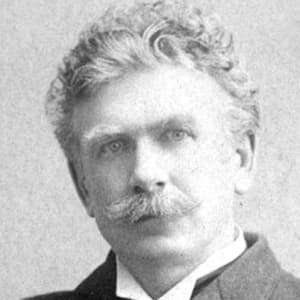

The title character and dramatic situation of El gringo viejo proceed from a still-unsolved historical mystery involving the American writer Ambrose Bierce. Students of American literature know him as “Bitter Bierce,” for Bierce wrote journalism and fiction that fairly dripped with his cynical disdain for human character and personality generally.

The short story collection In the Midst of Life: Tales of Soldiers and Civilians (1892), with stories that almost invariably end in death, provides a good example of Bierce’s downbeat sensibility. So, for that matter, does Bierce’s satirical The Devil’s Dictionary (1911), a thoroughly cynical lexicon that defines “love,” for example, as “a temporary insanity, curable by marriage.” No wonder they called him “Bitter Bierce.”

What may have drawn Fuentes to want to write about Bierce was the set of mysterious circumstances surrounding Bierce’s death. Bierce traveled into revolutionary Mexico in October of 1913 to report on the war there, and made his way from Ciudad Juárez to the city of Chihuahua. From that point on, Bierce simply disappears from history, his ultimate fate still unknown.

In El gringo viejo, Fuentes sets forth an imaginative recounting of what might have happened during Bierce’s last days. In this novel, Bierce is in Mexico because he wants to die; he has outlived his wife and his children, and he is monumentally tired of living. Yet he cannot take his own life – because one of his sons committed suicide, and Bierce cannot engage in an appropriation of his late son’s pain. Therefore he wants someone else to fire the fatal bullet, to put him out of his misery – and it is for that reason that he is in Mexico.

In composing El gringo viejo, Fuentes certainly had in mind this quote from a letter Bierce wrote to a cousin before crossing into Mexico:

“Good-bye — if you hear of my being stood up against a Mexican stone wall and shot to rags please know that I think that a pretty good way to depart this life. It beats old age, disease, or falling down the cellar stairs. To be a Gringo in Mexico — ah, that is euthanasia!”

Accordingly, Bierce has crossed the U.S.-Mexico border on what amounts to an elaborate suicide mission. His crossing of the border from the stability of the U.S.A. into the turmoil of revolutionary Mexico gives him considerable opportunity to meditate on frontiers both literal and metaphorical: “There’s one frontier we only dare to cross at night….The frontier of our differences with others, of our battles with ourselves.” Later, Bierce offers similar reflections that “I’m afraid that each of us carries the real frontier inside.”

Eventually, Bierce finds himself with troops commanded by General Tomás Arroyo, whose forces have liberated, and burned most of, the old Miranda estate on which he once lived as a young peon. The Mirandas, as Arroyo informs Bierce, were cruel hacienda owners, beating and mistreating the peons on any pretext. Arroyo always carries the old ownership papers from the hacienda, to emphasize that ordinary Mexican people like him always held the true title to the land – even though he cannot actually read the papers.

At the hacienda, the reader meets Harriet Winslow, a young Anglo woman from Washington, D.C., who traveled to Mexico to teach the children of the hacienda, only to discover that her prospective job has gone up in flames along with most of the hacienda. Bierce befriends Harriet, but holds back one crucial detail: “He did not tell her that he had come here to die because everything he loved had died before him.”

When General Arroyo destroyed almost all of the Mirandas’ hacienda, he spared the grand ballroom with its floor-to-ceiling mirrors; and when he shares the reason why with Bierce, he does so in a manner that emphasizes the poverty people like the Miranda estate’s peons have always known:

“They had never seen their whole bodies before. They didn’t know their bodies were more than a piece of their imagination or a broken reflection in a river. Now they know.”

“Is that why the ballroom was spared?”

“You’re right, gringo. For that very reason.”

“Why was everything else destroyed? What did you gain by that?”

“Look at those fields, Indiana General.” Arroyo gestured with a swift, weary movement of his arm which pushed his sombrero onto his shoulders. “Not much grows here. Except memory and bitterness.”

The book’s action depicts an episodic series of military actions, in a manner that recalls Mariano Azuela’s 1928 novel Los de abajo (The Underdogs). In one of those battles, Bierce single-handedly charges a group of federales, earning the admiration of the revolutionaries; but Bierce deflects their praise, saying, “It’s not difficult to be brave when you’re not afraid to die.”

In the breaks between military actions, the characters have opportunities to reflect on differences between Mexico and the United States. Bierce, for example, offers Harriet these reflections on racial attitudes in the two countries: “We are caught in the business of forever killing people whose skin is of a different color. Mexico is the proof of what we could have been, so keep your eyes wide open.”

Harriet, for her part, shows her own kind of ingenuity, saving a revolutionary’s life at one crucial point; and Bierce and Arroyo are both drawn toward Harriet. Bierce feels a sort of fatherly, protective affection toward Harriet; Arroyo’s feelings toward Harriet, meanwhile, are decidedly not fatherly, as a couple of spicy love scenes make clear.

The one thing that I found truly unfulfilling about The Old Gringo was the novel’s ending. Fuentes as novelist has given himself the challenge of concocting an explanation for Bierce’s still-unexplained disappearance in Mexico during the Revolution of 1910-20; but the manner in which he does so seems contrived – as if he feels he somehow has to work in a metaphor for the United States' often exploitative relationship with Mexico.

And I cannot blame him for wanting to do so. Consider that the combined impact of the Texas Revolution (1835-36), the Mexican-American War (1846-48), and the Gadsden Purchase (1854) was that almost one million square miles of resource-rich territory passed from Mexican to U.S. sovereignty. What thoughtful citizen of Mexico could not think about the process through which a neighboring country gained so much territory at the expense of their own? Yet Fuentes’ attempt to combine a necessary plot element with an historical allusion simply did not work for me.

None of that, however, takes away from the overall success of El gringo viejo – a highly popular novel that was adapted for cinema in 1989, with Gregory Peck as Bierce, Jane Fonda as Harriet, and Jimmy Smits as Arroyo. This book provides incisive characterizations, well-crafted imagery, and a thoughtful look at frontiers both literal and metaphorical; as Bierce once puts it, “each of us has a secret frontier within him, and that is the most difficult frontier to cross”.