What do you think?

Rate this book

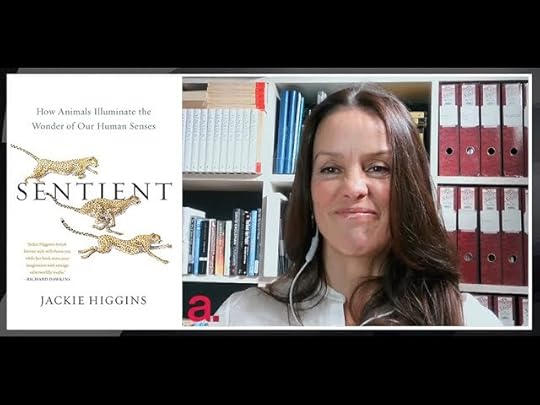

320 pages, Hardcover

First published June 24, 2021

"The word, from the Latin sentire, to feel, is so mercurial that the philosopher Daniel Dennett has, perhaps playfully, suggested, “Since there is no established meaning… we are free to adopt one of our own choosing.” Some use sentience interchangeably with the word consciousness, a phenomenon that in itself is so elusive as to reduce the most stalwart scientific mind to incantations of magic.

Marveling at how brain tissue creates consciousness, how material makes immaterial, Charles Darwin’s staunch defender T. H. Huxley once pronounced it “as unaccountable as the appearance of Djin [sic] when Aladdin rubbed his lamp.”