What do you think?

Rate this book

784 pages, Hardcover

First published November 10, 2020

In 492, Phrynikhos, a rival to Aeschylus presented a play that focused on the destruction of Miletus by the Persians, causing the audience to burst into tears, with the author being fined 1,000 drachmas for reminding the people of their own evils & forbidding all future performances of the play.

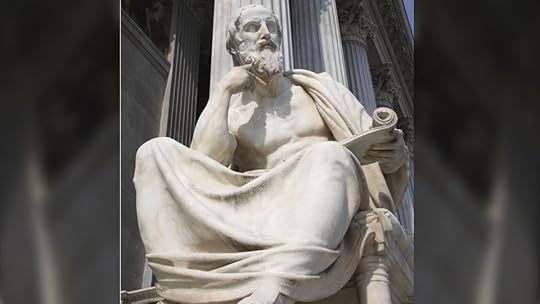

Thus Thucydides & Herodotus would have known that all poets & writers were primarily tasked with pleasing those who had come to hear them & so often made things up, even while declaring that they never did such things.

Herodotus, being aware of posterity, lamented that the absence of romance within his historical writings would probably limit interest in his work for future readers.

Herodotus, being aware of posterity, lamented that the absence of romance within his historical writings would probably limit interest in his work for future readers. The epic was invented after memory & before history, occupying a third space in the human desire to connect the present to the past. It is the attempt to extend the qualities of memory over the reach of time embraced by history.There is a discussion of history merged with myth, the Bible as history, the Synoptic Gospels as a form of history, with the comment that "all story-lines are full of interpretive fictions, self-censoring, a filling in of gaps & a forging of connections."

I suppose history never lies, does it?, said Mr. Dick, with a gleam of hope. Oh, no, sir! I replied most decisively. I was ingenious & young, and I thought so.At book's end, Cohen offers his readers some sage advice from William Prescott, author of History of the Conquest of Mexico & others works, who tells us that:

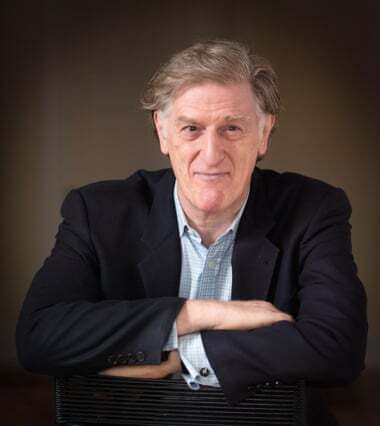

The historian must strive to be a paragon--strictly impartial, a lover of truth under all circumstances; he must be deeply conversant with whatever may bring into relief the character of the people he is depicting, not merely their laws, constitution, general resources & all the more visible parts of machinery of government but with nicer moral & social relations, informing the spirit which gives life to the whole.In the midst of this lengthy tome, there are names that will seem somewhat obscure if not even completely unfamiliar but I stayed on board for the the long ride. And, it might be said that there is too much peripheral commentary in Making History, especially the insertion of copious intersections with figures that Cohen has had a direct relationship with.

Beyond that, the historian must be conscientious to geography, chronology & so many other details, while always retaining a mastery of style. It is hardly necessary to add that such a monster never did & never will exist.