What do you think?

Rate this book

672 pages, Hardcover

First published May 10, 2012

Geoffrey of Anjou, the donor of sperm.

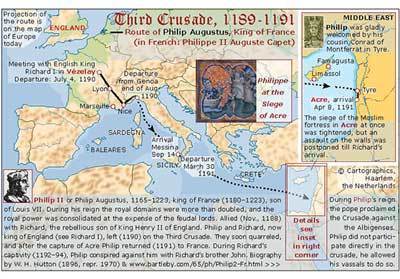

“he was carried onto the battlefield on a litter, covered in a gloriously regal silken quilt and carrying a crossbow, which he fired at Muslim defenders from behind a screen.”Philip II was a different story—Jones refers to his crusading career as a “catalogue of humiliation.” Finally (shoutout to Eric Cartman) he basically said, screw you guys, I'm going home.

“Philip II, driven by a cocktail of emotions that included jealousy, homesickness and exasperation, announced that he considered his crusading oath to have been served by the conquest of Acre. He was going home.”

“By the time Edward was born, there was a booming trade in Arthuriana, and a healthy industry had grown up around his imagined memory.”So, a great way to make a quick buck: pretend to find Arthur's skeleton and sell tickets for people to come check out the bones! Best business plan ever!

Along with his associate Simon de Reading, who had been tried alongside him, Despenser was roped to four horses and dragged through the streets of Hereford to the castle walls. There both men had nooses placed around their necks, and Despenser was hoisted onto a specially made fifty-foot gallows, designed to make punishment visible to everyone in the town. A fire burned beneath the scaffold, and it was here that Despenser’s genitals were thrown after the executioner scaled a ladder and hacked them off with a knife. He was then drawn: his intestines and heart were cut out and also hurled down into the flames. Finally, his body was lowered back to the ground and butchered. The crowd whooped with joy as his head was cut off, to be sent to London, while his body was quartered for distribution about the country.