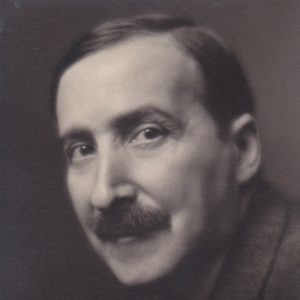

I was really pleased to have the opportunity to read and review this book, as I am a big fan of German Literature (especially Exilliteratur), but had never read anything before by Stefan Zweig. The book is a collection of his essays on his trips around Europe from 1902 to 1940, when he left Europe forever.

It took me a while to get into this book. I have visited most of the places Zweig writes about here, and initially I spent more time comparing my impressions of the places, than concentrating on what and how he was portraying them. I had loved Bruges – but found his depiction of the city (from about 100 years earlier) quite sombre and dismal:

“I was seized with a faint anguish about the notion of returning to this sepulchral town whose symbols embraced me with such power that I felt an infinite pity for these people who lived here in the shadows, inexorably on the path towards death, towards the incomprehensible.

It wasn’t until the more upbeat essay ‘Springtime in Seville’, which chimed with my experiences, that I began to pay attention to his writing, and enjoying both the excellent prose and the observations that he made.

“‘Quien no ha vista Seville, no ha visto maravilla’ – this proud aristocratic saying one hears until it becomes unbearable; and yet such vanity one can scarcely reproach. For is it not a miracle, when men and so many years of destiny reckon to build a town, and ultimately leave a smile drawn on the face of life?”

I found the imagery particularly beautiful in ‘Antwerp’.

There, they deposit from their wings the precious nectar, the goods. The cranes moan with pleasure when their fingers plunge into ships and exhume from the darkness objects of value drawn from distant lands. Now and then the wharves ring out with signals, great clocks hammer out an exhortation to the emigrants to exchange a last greeting, all languages of the earth resound together here. And at once you understand the sense of this town, too great for this small country: for it must be at the service of all Europe, of an entire continent

And in ‘Salzburg – The Framed Town’ the anthropomorphic description of the Salzach:

It’s an alpine river, small but rebellious, which in a mean mood can boil up during the melting period, impetuously crashing into the bridges and dragging along with it, by way of plunder, innumerable trees

I had spent a week in Chartres nine years ago, and every day went in the cathedral, each day finding something new and marvellous. I felt that Zweig perfectly captured the atmosphere of that amazing place.

“For one person or isolated individuals cannot create such marvels, which require whole centuries in order to exist properly, and for their immortality to ripen fully.”

“in answer they installed coloured panes in the caverns of the windows to lessen the burden of that grey light, allowing the sun to filter through all their colours, and so here too the myriad colourations of life made one sense even in this darkness a certain ecstatic bliss. These stained glass windows of Chartres are of a splendour without rival.”

“For this church had room for an entire generation and that is its heroic lesson, eternally big enough for all earthly aspirations, eternally able to exceed all possibilities and now forever a symbol of infinity”

There are three essays about places in England, and clearly Zweig was a fan of England and the English (at least until they locked him up as an ‘enemy alien’ at the outbreak of WWII). The first is ‘Hyde Park’:

“No – Hyde Park does not inspire dream, it inspires life, sport, elegance, liberty of movement.”

The book finishes with ‘House of a thousand Fortunes’ – a shelter for the dispossessed in London, which took care of hundreds of Jews fleeing the Nazis, among others:

“Adrift in the terrifying insecurity that has enveloped the lives of thousands like a glacial mist, at least for a few days he may feel the warmth and light of humanity – truly consoled at the heart of all this hopelessness he sees, he experiences it: that he is not alone and abandoned in this foreign country, no, rather he is linked to a community of his people and to the still higher community of mankind in general.

and ‘Wartime gardens’ that contrasts the ‘keep calm and carry on’ attitude of the English when war was declared in 1939, and the excited, holiday atmosphere in Vienna on the outbreak of WWI.

Zweig obviously loved travelling, but hated the new fashion of mass tourism, which he discussed in ‘Return to Italy’ (“more and more an invasion that washed ashore en masse the whole family of the provincial petit bourgeois”) and in ‘To Travel or be Travelled’:

“travel must be an extravagance, a sacrifice to the rules of chance, of daily life to the extraordinary; it must represent the most intimate and original form of our taste”

Zweig committed suicide in 1942, so he never got to see the horror of Ypres visited on Germany:

“Imagine if you will, to give comparison, a Berlin where the castles and the Linden were reduced to nothing but a smoking heap of debris”

But he also never got to see the European Union in all its glory, as “a new world that knows no national boundaries”.

This collection of essays gives a glimpse into the past – but is also a reminder of what we have now in the present, what we have lost and what we have gained, what has changed, and what still endures. Some of the essays I found very emotional – such ‘Ypres’ and ‘House of a thousand Fortunes’. Most of them, I really enjoyed.

I would like to read more by Stefan Zweig – perhaps even in German. But that is for another time.

I received this copy from the publisher via NetGalley in exchange for an honest review