What do you think?

Rate this book

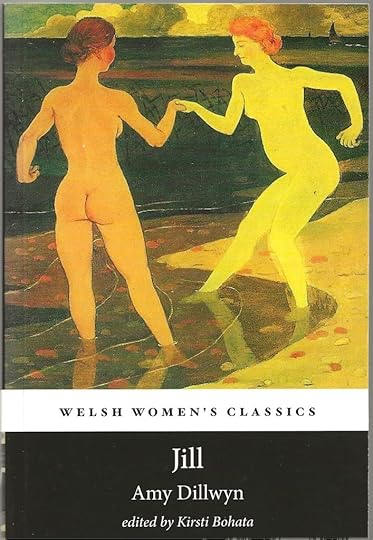

494 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1884

“The inevitable Mediterranean roll was in less force than usual when we crossed to Corsica, and as we were all pretty fair sailors we had a pleasant passage, notwithstanding the anticipations to the contrary of our especial waiter at the Cannes hotel. He was a brisk, cheery little fellow, with such a power of sympathising with other people that he always identified himself with those guests who were under his particular care, and took their affairs to heart almost as though they were his own. Going to sea and being sea-sick meant precisely the same thing to him; consequently, from the moment he heard of our contemplated trip he became full of compassion for the sufferings we must undergo, and was good-naturedly eager to think of, and suggest, every possible alleviation for the misery which he confidently predicted for us. As we departed from the hotel his final words were to impress upon my two ladies that, last thing before going to sea, one should always eat a hearty meal, because, "ça-facilite--et sans ça, c'est si fatigante." I am sorry to have to add, however, that this well-intentioned speech was received in by no means as friendly a spirit as that in which it was offered. For it was quite contrary to Mrs. Rollin's notions of propriety that one who was a man, and an inferior, should presume publicly to give her advice as to the management of her interior; so, instead of making the amicable response that was evidently expected, she swept past him with a freezing look and an audible remark to Kitty about the atrocious vulgarity of foreign servants who had never been taught to know their place." (Chapter XIV, At Ajaccio).