What do you think?

Rate this book

Paperback

First published June 24, 2021

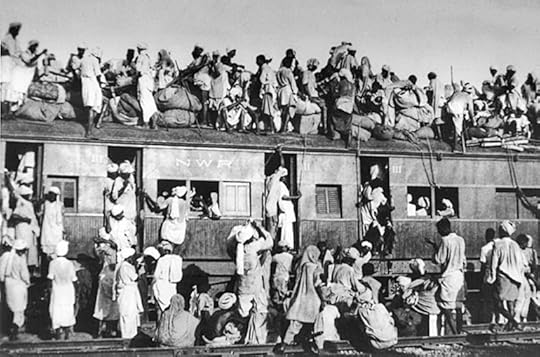

He remembers a train journey with his pa when he was a boy. The first time he has left the city. From Delhi to Madras. How he had leant out of the open dsoor, wind striking his face and body, exhilarated by the speeding landscape of temple town and market. Sacred shrines and connecting rivers. Buffalo submerged in muddy waters and rows of dusty cornfields. Holy cows tethered. He had known then the value of his ancient homelands: that India was many complexities of tribe and dialect and ritual woven together, an inextricable fabric of pulsating life. How could anyone put borders on that?

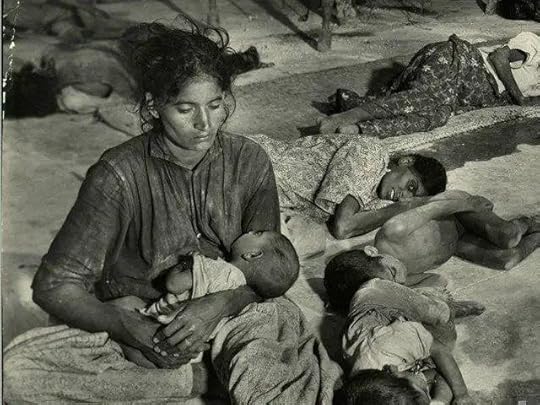

It was a need to write about something political, intimate and about women that led Razak to the trauma of Indian Partition in 1947. Listening to the radio one night in her cafe, she heard a show called Partition Voices –– interviews of elderly survivors and their experiences of living through the Partition of India. She was moved. “It wasn’t just about the political and geographical rupture in India. It was ruptures between families, between friends, between people because there was so much love there. And that was kind of ripped apart,” she said.

The name Moth came from a very unprecedented event in Razak’s life. There had been a moth infestation in her flat on her beloved pashmina scarves collected from India over the years of travel. “I picked one up and it just crumpled into dust in front of me. And it was really that feeling of it falling apart that made me think of the situation and Partition,” she said. She also remembers Jinnah’s words where he compared Pakistan to a moth-eaten country with separate parts in separate places. This was an image Razak couldn’t get out of her mind.