What do you think?

Rate this book

576 pages, Paperback

First published September 24, 2019

“She does not want to remember but she is here and memory is gathering bones”

“Tell them Hirut, we were the Shadow King. We were those who stepped into a country left dark by an invading plague and gave new hope to Ethiopia’s people”

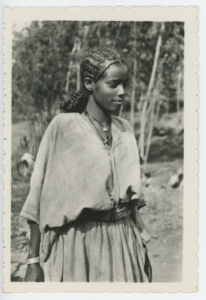

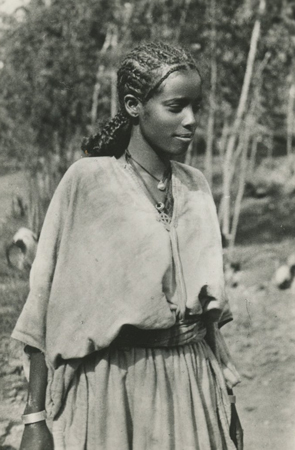

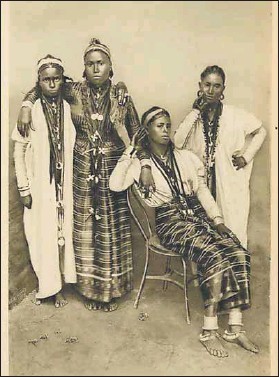

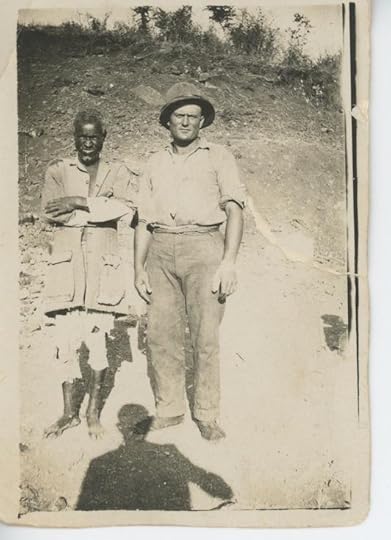

I made a very deliberate decision not to put photographs in the book. There are two, the bookends. Writing the word-images inside book was my way of thinking about how to move beyond “bearing witness”—where the witness is always outside and bearing the burden of witnessing—and the act of looking is an unwieldy responsibility that’s put on that person, and it’s not a natural thing, it’s a weight. I’ve been questioning for a long time how to eliminate that. The photograph is a weapon, it’s a sign of power and it’s still being turned on people. Those who are looking are not the ones bearing anything. It is those depicted in the frame who hold the balance of the weight. How do we honor that, respectfully, and see ourselves in every image we make?

"Tell them, Hirut, we were the Shadow King. We were those who stepped into a country left dark by an invading plague and gave new hope to Ethiopia's people."

The real emperor of this country is on his farm tilling the tiny plot of land next to hers. He has never worn a crown and lives alone and has no enemies. He is a quiet man who once led a nation against a steel beast, and she was his most trusted soldier: the proud guard of the Shadow King. Tell them Hirut. There is no time but now. She can hear the dead growing louder: we must be heard. We must be remembered. We must be known. We will not rest until we have been mourned. She opens the box.

A memory: her father taps her chest the first day he lets her touch the rifle. This is life, he says. Then he settles his palm on the gun, This is death. Never underestimate either.

An Album of the Dead

Twins, bound back to back. A young man caught mid-movement, features a blur except for that open mouth. A boy, lanky and broad shouldered, hands clasped together to beg. An old woman, immobile, defiant, chin up, eyes blazing. A man, face beaten beyond recognition, a series of swollen, broken features. A couple, wife clinging to husband, face buried in his shoulder, his ripped shirt exposing a long, angry cut. Two young men, wild curls thick against their necks, gripping hands, face-to-face, eyes only for each other. A young man, rigid as a soldier, a bloom of dark curls framing a furious and handsome face. A young man, bookish, eyeglasses, trembling, shaking head forcing a sweep of blurry features. A young man, hands bound behind his back, shoulders protruding painfully, a tender neck jutting forward, lips pursed to spit. A girl. A young woman. A nun. Two slack-mouthed beggars, Three deacons, steady eyes. Another girl. A young man, his brother, his father, identical faces, reshaped by blows, equally swollen. A girl buckling from fear, the top of her head, the face twisted in anguish and confusion. A girl, a woman, a young man, an elderly man, a man and his wife, a family of three, a defiant old man, a brother and sister refusing to let go of each other, a bent-backed woman, a tall, lithe boy. A blind man, opaque eyes. Twins again, bound back to back.

Signature: Ettore Navarr, soldato e fotografo

Signature: Colonello Carlo Fucelli, Ricordi d’Africa