“The title ‘United Kingdom’ when pronounced by Adah’s father sounded so heavy, like the type of noise one associated with bombs. It was so deep so, mysterious, that Adah’s father always voiced it in hushed tones, wearing such a respectful expression as if he were speaking of God’s Holiest of Holies. Going to the United Kingdom, then, must surely be like paying God a visit. The United Kingdom, then must be like heaven.”

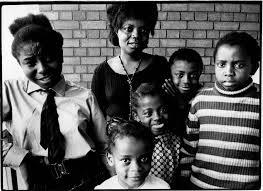

Ever since her childhood in Nigeria, Adah wanted to see England. Married off at 16 to Francis, when he travels there to study, she follows along with their two small children. She’s barely 18, it’s the early 1960s and England’s a far colder place than Adah ever imagined.

Buchi Emecheta’s semi-autobiographical novel covers territory that might seem familiar, the racism of 1960s’ London, its poverty, everyday challenges like finding landlords who’ll accept black tenants, and the impact of suddenly being treated like a ‘second-class citizen.’ But, unusually for its time, it covers this from a woman’s perspective. And Emecheta’s focus here’s just as much, if not more, on Adah’s internal battles, her difficult journey to independence. Adah’s been taught her purpose is to pay for Francis’s education, and produce babies – as long as they aren’t all ‘insignificant’ girls. This is what’s expected so it’s what Adah does, meanwhile Francis does what he pleases, takes her money, sleeps around and is increasingly abusive. Adah’s cut off from a community that might help her with these problems, issues of class and background separate her from the other black families she encounters, almost as much as from the white people she meets. But after giving birth for the third time in rapid succession, Adah realises if she’s going to survive, she has to come up with a plan or she’ll be overwhelmed by the double weight of racism and misogyny.

Emecheta’s style is simple and direct, her well-crafted prose has a slightly informal quality, echoing Adah’s voice and thoughts. But the novel’s real strength is the compelling story; the sensitive depiction of Adah’s, not-always-likeable, character; and the complex underlying questions Emecheta’s highlighting around postcolonialism, cultural difference, identity and patriarchy. This also stands out for its immediacy, unlike most available books representing similar episodes in England’s inglorious past, Andrea Levy’s impressive portrayal of the Windrush generation in Small Island for example, Emecheta isn’t looking back on history in an attempt to recreate it, she’s drawing directly on her own.

Rating: 3.5

(prequel to In the Ditch)