What do you think?

Rate this book

308 pages, Paperback

First published July 19, 2022

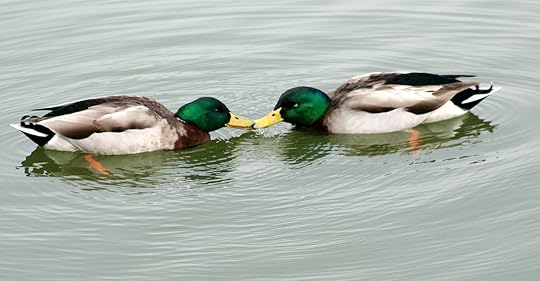

Aligned with the toxic and the unnatural, the birds are anthropomorphized and their sexualities moralized according to human biases, their gayness takes as proof that their environment is poisonous.

[...]

Perhaps the gay bird are enjoying their new carefree, childless lifestyles. Perhaps some of these birds find aspects of preduction a burden. [...] From whose perspective is reproductive success the ultimate definition of success? God's, Darwin's, ecologists', or the animals'?

[...]

Why [is] bird sexuality any of our business? It's true that birds have not had a choice in the matter - but then again, who does? Most people on the planet absorb a number of extrememly toxic pollutants without prior consent too.

[...]

Ideas about what is clean vs toxic are constantly in flux. One day a newspaper touts the benefits of chocolate and red wine in moderation; the next it touts abstinence.

‘Only Saint John the Baptist, the beheaded megasaint, stares directly out of his frame at the viewer. — Lucia’s own eyes were said to have been plucked or maybe stabbed out. She is the patron saint of eyesight because of this grisly martyrdom. — Your pain and hers, back and forth. Ouch, ouch. I love Lucia. I love the weirdness of her extra eyes — .’