Francis Sancher was dead to begin with. Not dissimilar to Jacob Marley in the classic Charles Dickens tale, "A Christmas Carol", the mysterious central character of Maryse Conde's novel "Crossing the Mangrove" is introduced to the reader in the form of a corpse. It is only through the internal dialogs and reminiscences (of questionable veracity) by the citizens of Riviere au Sel at Sancher's wake that we learn who he might have been, and what might have led him to end up face down in the mud of this small hamlet on the Caribbean island of Guadeloupe.

While at first it appears that the thrust of "Crossing the Mangrove" is to delve into the life and death of one Francis Sancher, who inevitably may or may not be exactly what he seems, what lies in fact at the heart of this novel is an examination of our own perceptions of the people around us, and the roles they play in our every day lives. Over the course of a night, one by one the characters unravel their own stories and speculate on the stories of their neighbors, each supposing over the role that they played in bringing Francis Sancher closer to the "bad end" they all said was eventually coming his way.

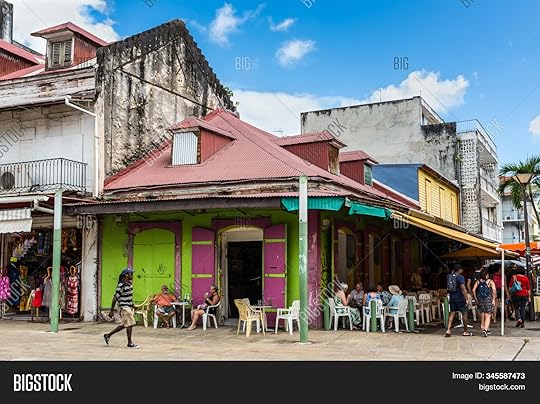

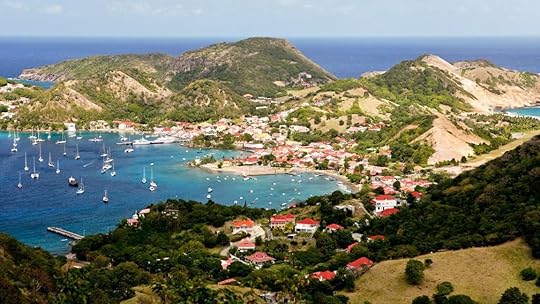

By far, aside from the cast of characters that make up the citizenry of Riviere au Sel (a group that could put our modern "Real" or "Desperate" housewives to shame), what shapes the tone and atmosphere of "Crossing the Mangrove" is the island of Guadeloupe itself. In her lush descriptions of the flora and fauna of the Caribbean, and deft use of metaphor, Conde reminds the reader that prejudices and perceptions, like the roots of the mangrove tree itself can cause a person to "be sucked down and suffocated by the brackish mud." It comes as no surprise that the author herself hails from Guadeloupe, and through seeing the island and its intrigues through her eyes, the reader too feels that they have become intimately familiar with this place where "death is nothing but a bridge between humans, a footbridge that brings them closer together on which the can meet halfway to whisper things they never dared talk about." If it sounds dark in Conde's Guadaloupe, it is. But ultimately, this journey of perception and introspection, of the clinging closeness of the climate, of the small town of Riviere au Sel and it's people as they react to the death of this interloper reveals something hopeful - that despite differences of race, of caste, of circumstance, the congregation as a whole is still greater than the sum of its disparate parts.

Originally published in 1995 as "Traversee de la Mangrove" in her native French tongue, this is not one of Conde's most popular novels. That honor goes to "Segu", a historical novel about the rise of Islam in 18th Century Africa. Honestly, given the choice, the plot of "Segu" sounds much more like the type of novel I would typically be drawn to. But having now experienced Conde's florid prose in the context of this psychological search for truth, camouflaged in the pretense of an atypical murder mystery, it's likely I would follow her anywhere, even if it meant traversing a mangrove swamp itself.