What banal and unadulterated drivel!

I must begin by stating for the record that I am not religious. And it would not be appropriate to place me in any distinct “belief” category since even I cannot. But I am continually amazed and saddened by the audacity of those who purport with their writings to tell the story of a person’s life yet distort that biographical record so completely and, in the case of the illustrious Vincent van Gogh, so unashamedly. I refer to the 976-page tome by former Pulitzer-winning authors Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith under the somewhat unimaginative title of Van Gogh: The Life (Random House, 2012).

Telling the story of another person’s life comes with a formidable responsibility, as with the recording of all true events. Biographers are documentarians and by definition set down evidence for those who come after them. In doing so, they must connect with the essence of the subject on a factual level as well as on an intellectual and emotional level. Biography is, after all, the recording of a person’s life; and if I as biographer rush to judgement or am slipshod with facts, I not only besmirch that person’s life but violate the trust of future generations to come. The historical record would be flawed.

As I have stated, I am not a religious man by any means but my beliefs have nothing to do with biographical integrity. In my opinion, a good deal of the ruminations of Naifeh and Smith in Van Gogh: The Life are in reality mere speculation, and certainly lack journalistic integrity. Their protracted opus, had it been confined to fact, would have been half its size. It is suffused with conjecture . . . some might say claptrap. And there’s a lot of it. The tangible evidence revealed in Vincent van Gogh’s own beautifully written and reverent letters, of which over 900 exist, seems to have been ignored by the book’s authors (notwithstanding the thousands of citations on the book’s website) in their desire to sensationalize.

The Washington Post, in a review of Van Gogh: The Life, had this to say:

“Marvelous . . . [Van Gogh: The Life] reads like a novel, full of suspense and intimate detail . . . In beautiful prose, Naifeh and Smith argue convincingly for a subtler, more realistic evaluation of Van Gogh, and we all win.”

Actually, we all lose. There’s no doubt that the book reads like a novel because it is serves up a lot of fiction, and is full of presumption and supposition. Read Vincent’s own letters if you doubt that. Someone once said, “Well, every biography has some conjecture. It’s the nature of the beast.” I disagree. Postulation perhaps—an intellectual questioning as a basis for reason. But conjecture is the forming of an opinion based on incomplete or inaccurate information. How this book and its polemics argue for “… a subtler, more realistic evaluation of Van Gogh” is beyond me. The record clearly shows otherwise. And the prose is not so much beautiful as garrulous.

Here’s what Naifeh and Smith say about Van Gogh’s painting of his father’s Bible:

“When he finally achieved the color he was looking for—a deep, pearly lavender gray, equal parts Veronese’s wedding banquet, Hals’s bourgeois militiaman, and the dead flesh of Rembrandt’s corpses—he ‘detonated’ it on the canvas in a hail of vandalizing brushstrokes in place of the neat blocks of text.”

One can’t help but wonder how the authors knew what color Vincent was looking for. Nowhere in the record does Van Gogh say he’s looking for “a deep lavender grey” let alone any reference to Veronese, Frans Hal, and certainly not “the dead flesh of Rembrandt’s corpses”. “Detonating” paint onto canvas may have worked for their (also questionable) treatment of Jackson Pollok but it’s a bit over the top for Van Gogh. And their “hail of vandalizing brushstrokes” starts in me a kind of literary nausea. I get the strong notion that Naifeh and Smith’s writing is mere loquaciousness, and certainly demonstrates that they are less familiar with art history than their chosen profession as lawyers, and lack the ability to craft an honest biography. Then comes:

“As he finished the book and the draped table, the clash of complementaries played itself out in an argument of broken tones applied with an increasingly broad and confrontational brush. To complete this chronicle of rejection, grief, self-reproach, and defiance, Vincent added at the last minute a new object—an extinguished candle—the final snuffing out of the ‘rayon noir’, and a confession that he could never make any other way.”

Amazing rhetoric. Astounding conjecture. Clever alliteration. But little veracity. The overall impression one takes away from Naifeh and Smith’s book is well expressed in reviews on Amazon.com. One of them by Richard A. Schindler stands out:

‘The excessive focus on almost every moment of Vincent’s personal life and relationships paints a portrait of an ungrateful, wretched, belligerent, obsessive, delusional (a word used numerous times) son, brother, employee, and friend. The letters are exhaustively (and I mean exhaustively) combed for passages that purportedly reveal a man who lived a life of passionate renunciation of the truth and mightily abused anyone who happened to cross his path.

“Oh yeah, he happens to make some great art in the last four years of his life. The analysis of the art occasionally provokes some insights into Vincent’s influences and his application of a vast internal compendium of art, literature, and religion to all of his work. However, the individual works are either given cursory treatment or relegated to a kind of elevated descriptive exegesis. For example, the section on “Still Life with Open Bible” (1885) ignores Vincent’s great respect for the Bible and the central significance of the passage from Isaiah as it relates to the subject and hero of Emile Zola’s “La Joie de vivre”.

“When will we be freed of these monstrous biographies that purport to give us some psychological insight into the minds of artists? The Jackson Pollock bio was character assassination through labored and pseudo-intellectual analysis of every aspect of his life and art. Van Gogh: The Life (the hubris!) is more of the same, but with better pictures. The authors are graduates of Harvard Law School and it looks like they want to put their subjects in a dock and prosecute the life out of them.”

~ Richard A. Schindler, Amazon.com, February 26, 2012.

While there are many who have given the book glowing reviews on Amazon.com, one wonders if any of them took the time to read some of Van Gogh’s complete letters (freely available on the Van Gogh Museum’s website) rather than believe in the trite techniques of obfuscation used by Naifeh and Smith to paint their subject in “fathomless grey”. Parts of Van Gogh’s letters have been deliberately, it seems, taken out of context, and interpreted to suit the authors’ motives. One wonders what possible motives these people would have for denigrating a man’s life, especially that of a man so well known and loved for his generosity of spirit and innumerable acts of kindness. And that’s not supposition; it’s fact.

Naifeh and Smith would have you believe that Van Gogh turned away from God over the course of his brief life and, using a skewed interpretation of one of Vincent’s letters, that his was a “fanatic heart”—that he was a fractured and frenzied soul. They are quick to use sentences and phrases such as:

“Long after others had put away the breathless manias of youth, Vincent still lived by their unsparing rules.”

‘”These storms of zeal had transformed a boy of inexplicable fierceness into a wayward, battered soul: a stranger in the world, an exile to his own family, and an enemy to himself.”

” . . . the price Vincent paid in loneliness and disappointment for his self-defeating, take-no-prisoners assaults on life . . .”

” . . .all those who dismissed Vincent’s paintings—or his letters—as the rantings of the wretched, as most still did.”

What unadulterated, hackneyed nonsense has been spawned by these two authors. And the damage done to Van Gogh’s legacy is immeasurable. Naifeh and Smith, in my view, misinterpret passion for fanaticism. They smear youth as having “breathless manias” and that youth as a whole is “unsparing”. The hyperbole is disturbing. If I were young, I’d be insulted. But don’t just take my word for it; read the facts. Read Vincent’s own letters—completely, not partially. And with an open mind that, like Van Gogh’s, begins with a kind heart, and not one that seeks to besmirch and sensationalize at the cost of truth, or to engage in the wanton denigration of a person’s character.

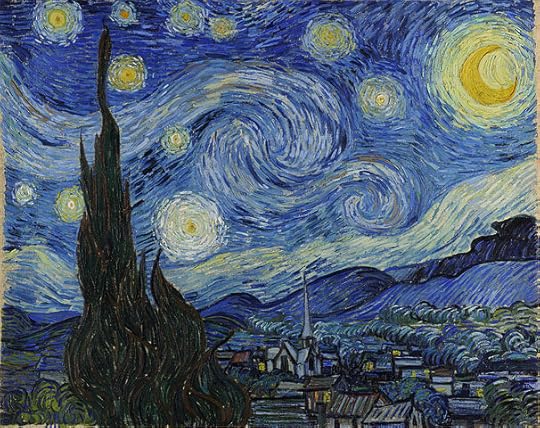

Vincent van Gogh’s letters remain today some of the finest examples of prose in existence. And they illustrate, over and over, a mind that could not have been so fractured and frenzied; it would never have been able to see the minute details of human existence—his powers of observation were remarkable—and to write those down so eloquently and with such warmth and caring. And then to transform those scenes into the powerful (and undeniably compassionate) drawings and paintings that are his enduring legacy.

Ten years before his untimely death, Van Gogh wrote:

“Now likewise, everything in men and in their works that is truly good, and beautiful with an inner moral, spiritual and sublime beauty, I think that comes from God, and that everything that is bad and wicked in the works of men and in men, that’s not from God, and God doesn’t find it good, either. But without intending it, I’m always inclined to believe that the best way of knowing God is to love a great deal. Love that friend, that person, that thing, whatever you like, you’ll be on the right path to knowing more thoroughly, afterwards; that’s what I say to myself. But you must love with a high, serious intimate sympathy, with a will, with intelligence, and you must always seek to know more thoroughly, better, and more. That leads to God, that leads to unshakeable faith.

“Someone, to give an example, will love Rembrandt but seriously, that man will know there is a God, he’ll believe firmly in Him.

“Someone will make a deep study of the history of the French Revolution—he will not be an unbeliever, he will see that in great things, too, there is a sovereign power that manifests itself.

“Someone will have attended, for a time only, the free course at the great university of poverty, and will have paid attention to the things he sees with his eyes and hears with his ears, and will have thought about it; he too, will come to believe, and will perhaps learn more about it than he could say.

“Try to understand the last word of what the great artists, the serious masters, say in their masterpieces; there will be God in it. Someone has written or said it in a book, someone in a painting.”

~ Vincent van Gogh, c. June 22-24, 1880.

And then, just two years before his death, Vincent—this man whose letters Naifeh and Smith would have you believe were ” . . . the rantings of the wretched . . .” and who had moved away from his core Christian beliefs—wrote these exquisite lines:

“Christ alone—of all the philosophers, Magi, etc.—has affirmed, as a principal certainty, eternal life, the infinity of time, the nothingness of death, the necessity and the raison d’etre of serenity and devotion. He lived serenely, as a greater artist than all other artists, despising marble and clay as well as color, working in living flesh. That is to say, this matchless artist, hardly to be conceived of by the obtuse instrument of our modern, nervous, stupefied brains, made neither statues nor pictures nor books; he loudly proclaimed that he made . . . living men, immortals. This is serious, especially because it is the truth. . .

” . . . And who would dare tell us that he [Jesus] lied on that day when, scornfully foretelling the collapse of the Roman edifice, he declared, Heaven and earth shall pass away, but my words shall not pass away. . . .

‘”. . . But seeing that nothing opposes it—supposing that there are also lines and forms as well as colors on the other innumerable planets and suns—it would remain praiseworthy of us to maintain a certain serenity with regard to the possibilities of painting under superior and changed conditions of existence, an existence changed by a phenomenon no queerer and no more surprising than the transformation of the caterpillar into a butterfly, or the white grub into the cockchafer.

“The existence of painter-butterfly would have for its field of action one of the innumerable heavenly bodies, which would perhaps be no more inaccessible to us, after death, than the black dots which symbolize towns and villages on geographical maps are in our terrestrial existence.”

~ Vincent van Gogh, 1888

It is difficult to contemplate how these words could have been written by Naifeh and Smith’s “. . . wayward, battered soul: a stranger in the world, an exile to his own family, and an enemy to himself.” This apparently fractured man in fact said in a letter to Anthon van Rappard, in 1883:

“The more one loves, the more one will act, I believe, for love that is only a feeling I wouldn’t even consider to be love . . .”

Vincent van Gogh proved many times in his life to have been a man of great kindnesses supported by action. There are scores of examples of his acts of benevolence that bely the exegeses in Van Gogh: The Life. One of the more clear-thinking reviewers on Amazon.com, Kathleen Anderson, wrote:

“The highest spiritual glory in Vincent’s personal life was first expressed in his intention to serve those most in need, to value those rejected by social constructs. He gave up all to bring the divine in Christian understanding to the miners in the ministry of his early manhood. This is evidence of sacrificial love, the highest love, of which Jesus Christ was the example for Vincent. I remain unconvinced that Vincent ever turned away from God; his call to ministry seems to me to have evolved into visual witness of the glorious gifts God gives to humanity. I have no sense of this from the authors of the book, ‘Van Gogh: The Life’.”

~ Kathleen Anderson, Amazon.com, February 24, 2012

Vincent van Gogh was, by dint of his own writings, an ardent Christian. That he retreated from the organized church early in life is not in dispute. He despaired of the hypocrisy of the clergy with whom he was first connected in the Borinage mining region, an order that to Vincent was one of words and appearances rather than deeds. However, his faithfulness to core Christian principles never waned. This is plainly evident not just in his words but in his actions.

From his earliest days, Vincent van Gogh was conditioned to take action on behalf of the needy. He was the son and grandson of two welfare pastors stationed in the rural south of the Netherlands, and as a young boy had often accompanied his father on missions to deliver clothing and food to the poorest of the peasants in the region. Accounts of Vincent and his family working as nurses are also well substantiated.

Even the cynical and controversial post-impressionist painter, Paul Gauguin, wrote admiringly of how Vincent had nursed severely burned miners back to life during his days in the Borinage region. Many of those injuries included firedamp explosions in the mines of the 19th century, the result of dangerous working conditions that routinely led to death and dismemberment. Van Gogh sacrificed his clothing and bed sheets as bandages for the wounds of severely burned victims. This caused him to have an unkempt appearance which angered his Evangelical superiors who insisted on a dress code for members of the clergy. Ultimately he was dismissed because of his refusal to accede to their admonishments, preferring instead to minister through good deeds. However, those whom he had cared for admired his devotion to them, and his acts of kindness were instrumental in bringing the true Gospel messages to many of them.

The following account from Johanna van Gogh-Bonger, Vincent’s sister-in-law, is particularly revealing:

“Some of his characteristics have been remembered vividly. When the miners of Wasmes went to the pits, they put old vests made of sacking over their linen work clothes, using them like pea jackets to protect themselves in the cages, from water spurting from the walls of the shafts. This miserable raggedness kindled Vincent van Gogh’s pity most deeply. One day he saw the word ‘fragile’ printed on the sackcloth on one miner’s back. He did not laugh. On the contrary, for many days he spoke about it compassionately at mealtimes. People did not understand. . .

“An epidemic of typhoid fever had broken out in the district. Vincent had given everything, his money and his clothes, to the poor sick miners. An inspector of the Evangelization Council had come to the conclusion that the missionary’s “exces de zele” bordered on the scandalous, and he did not hide his opinion from the consistory of Wasmes. Van Gogh’s father went from Nuenen [sic] to Wasmes. He found his son lying on a sack filled with straw, horribly worn out and emaciated. In the room, dimly lit by a lamp hanging from the ceiling, some miners with faces pinched with starvation and suffering crowded round Vincent. . .

“. . . Van Gogh made many sensational conversions among the Protestants of Wasmes. People still talk of the miner whom he went to see after the accident in the Marcasse mine. The man was a habitual drinker, ‘an unbeliever and blasphemer,’ according to the people who told me the story. When Vincent entered his house, to help and comfort him, he was received with a volley of abuse. He was called especially a macheux d’capelets [rosary chewer], as if he had been a Roman Catholic Priest. But Van Gogh’s evangelical tenderness converted the man.”

~ Van Gogh-Bonger 1978/1914, 1:226

Now read how absurd the words of Naifeh and Smith are in the Prologue of Van Gogh: The Life:

“No one knew better than Theo—who had followed his brother’s tortured path through a thousand letters—the unbending demands that Vincent placed on himself, and others, and the unending problems he reaped as a consequence. No one understood better the price Vincent paid in loneliness and disappointment for his self-defeating, take-no-prisoners assaults on life . . .”

What banal and clichéd drivel. There’s hardly a letter written by Vincent van Gogh that would give any open-minded reader such ideas.

I will allow that Van Gogh’s relationships with members of his immediate family were at times strained. But the idea put forward by Naifeh and Smith that these were of a permanent or irredeemable nature is patently false. The raising of children into responsible adulthood is fraught with angst and often with trauma. Yet most parents would never give up on their kids, no matter what. The Van Goghs were no exception. Vincent caused his father and mother great anxiety over the course of his brief life; and he bore at times antipathy towards them. But if you know the real story, one devoid of sensationalism for sensationalism's sake, Vincent's relationship with his family was redeemed prior to his death, and very much so afterward.

If you want to read a truly good book on Vincent's life, read "Van Gogh's Untold Journey" by William J. Havlicek, Ph.D. and the forthcoming book "Johanna: The Other Van Gogh" by Havlicek and Glen. Those books are based on facts, not conjecture like Van Gogh: The Life.