Misanthropy can be defined as hating human beings for having the nerve to be human. The misanthrope, himself a member of the human species, sets himself up on a lofty pedestal from which he can look down and denounce the follies and weaknesses of his fellow humans. The misanthrope savours his sense of moral superiority, while offering no remedy, no suggestion for reform, no ideas for how to make things better for poor flawed humankind. The pose of the misanthrope is fundamentally self-aggrandizing and ultimately self-defeating – all of which Molière makes clear in his 1666 play The Misanthrope.

The 17th century was a landmark era for French drama, largely because of Molière. Where Jean Racine specialized in stark, classically influenced tragedy, Molière made the comedy of manners his true métier. The France of King Louis XIV – a place where the most appalling crimes and misdeeds could be committed under the cover of flawlessly polite conduct – was, arguably, the perfect place for a comedian of manners to perfect his craft: indeed, there was a persistent and longstanding rumour (albeit one unsupported by the facts) that Louis XIV once invited Molière to dine with him at Versailles!

In point of fact, dinner for two with France’s Sun King was not in the cards for Molière, whose interactions with the French Government were much more problematic than that. By the time Molière wrote The Misanthrope, two of his most recent plays, Tartuffe the Hypocrite (1664) and Dom Juan (1665), had been banned by the French royal government for supposed anti-clerical and anti-government attitudes. The Misanthrope avoids such potential troubles by keeping its satirical focus solely on the way in which people interact and treat one another in the Parisian high society of Molière’s time.

The misanthropic title character of Molière’s play is Alceste, a man who takes pride in rejecting the polite social conventions of the Paris of his time, and seems to embrace the isolation that results, insisting that “I would have people be sincere, and that, like men of honor, no word be spoken that comes not from the heart” (p. 1).

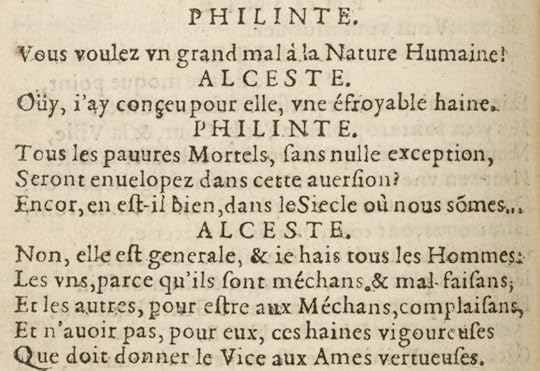

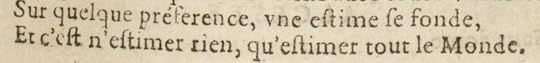

Alceste’s friend Philinte, a young man of good will, suggests that one should try to reciprocate shows of good feeling from others, but Alceste is unpersuaded, stating that “Preference must be based on esteem, and to esteem everyone is to esteem no one. Since you abandon yourself to the vices of the times, zounds! – you are not the man for me. I decline this over-complaisant kindness, which uses no discrimination. I like to be distinguished; and, to cut the matter short, the friend of all mankind is no friend of mine” (p. 1).

Alceste’s view of humankind is singularly grim – “Everywhere I find nothing but base flattery, injustice, self-interest, deceit, roguery. I cannot bear it any longer: I am furious; and my intention is to break with all mankind” (p. 2). And when Philinte, seeing the grossly essentialist quality of Alceste’s misanthropy, asks if there are no exceptions to Alceste’s harsh attitude toward human beings, Alceste insistently replies, “No, they are all alike; and I hate all men: some, because they are wicked and mischievous; others, because they lend themselves to the wicked, and have not that healthy contempt with which vice ought to inspire all virtuous minds” (p. 3).

Philinte, a voice of reason (and something of a choral figure), urges Alceste, in a spirit of Enlightenment rationality, to moderate this harsh outlook, stating that “Good sense avoids all extremes, and requires us to be soberly rational. This unbending and virtuous stiffness of ancient times shocks too much the ordinary customs of our own; it requires too great perfection from us mortals; we must yield to the times without being too stubborn; it is the height of folly to busy ourselves in correcting the world” (pp. 3-4).

In that connection, Philinte points out that Célimène, the beautiful young woman whom Alceste loves, has faults of her own, and asks, “How comes it that, hating these things as mortally as you do, you endure so much of them in that lady? Are they no longer faults in so sweet a charmer? Do you not perceive them – or if you do, do you excuse them?” Alceste replies that “I confess my weakness; she has the art of pleasing me. In vain I see her faults: I may even blame them; in spite of all, she makes me love her. Her charms conquer everything, and, no doubt, my sincere love will purify her heart from the vices of our times” (pp. 5-6). Here, one sees the arbitrary and illogical qualities of Alceste’s misanthropy: he can’t admit that he desires Célimène because she is beautiful, charming, and much-sought-after; rather, he must tell himself lies to the effect that his “sincere love” will somehow “purify her heart” in a sort of redemptive act.

Philinte points out that Célimène’s cousin Éliante, who also fancies Alceste, possesses qualities of stability and sincerity that Célimène lacks. When Philinte suggests that Éliante would be a better match for Alceste, Alceste replies that “It is true: my good sense tells me so every day; but good sense does not always rule love” (p. 6).

Alceste’s life of comfortable, smug, self-satisfied misanthropy becomes more complicated when Oronte, a well-connected nobleman who is one of Célimène’s other suitors, shares his new sonnet with Alceste. Alceste is cruelly dismissive of Oronte’s literary efforts – from his point of view, he is simply being “honest” – but he has now publicly insulted an aristocrat with powerful connections at the highest levels of the French court. Alceste’s arrogant decision to make an enemy of Oronte will have consequences for the misanthrope later on.

With all the build-up regarding Célimène’s beauty and her character flaws, the reader or playgoer is likely to be anxious to meet her – and she is indeed a tour de force of a character. As the first conversation of the play between Alceste and Célimène unfolds, one gets the sense that Alceste’s efforts to “correct” Célimène’s behaviour will be unavailing. When Alceste insists that “Too many admirers beset you; and my temper cannot put up with that”, Célimène blithely replies by asking, “Am I to blame for having too many admirers? Can I prevent people from thinking me admirable? And am I to take a stick to drive them away, when they endeavour by tender means to visit me?” (p. 13). Clearly, Célimène likes being admired; her vanity at being much-sought-after matches Alceste’s excessive self-regard at his supposed “honesty.” As for Alceste, the I-love-you-against-my-own-will quality of his expressed affection for Célimène makes it understandable why Molière gave this play the alternate title l'Atrabilaire amoureux (The Cantankerous Lover).

Clitandre and Acaste, two marquises who are also courting Célimène, come to visit. Alceste wants to leave, but Célimène insists that he stay. During the visit, Clitandre and Acaste, like conventionally gallant would-be lovers, both insist that they see no faults in Célimène; Alceste, as always, insists on going his own way when it comes to courtship: “The more we love any one, the less we ought to flatter her. True love shows itself by overlooking nothing” (pp. 19-20). It makes one wonder: are Célimène’s attentions to Alceste part of her vanity? Is it a case of “I’m such a beautiful and charming woman that I can even make France’s most notorious misanthrope love me”?

The theme of hypocrisy – of inconsistency between how people define good behaviour, and how those same people actually behave in private life – is as prevalent in The Misanthrope as it was in Tartuffe the Hypocrite. When Arsinoé, an older friend of Célimène, goes to Célimène to suggest that Célimène’s entertaining of so many gentlemen who come-a-courting is compromising her reputation, Célimène is unsparing in pointing out the inconsistencies between Arsinoé’s own words and actions:

As I see you prove yourself my friend by acquainting me with the stories that are current of me, I shall follow so nice an example, by informing you what is said of you. In a house the other day, where I paid a visit, I met some people of exemplary merit, who, while talking of the proper duties of a well-spent life, turned the topic of the conversation upon you, madame. There, your prudishness and your too-fervent zeal were not at all cited as a good example. This affectation of a grave demeanour, your eternal conversations on wisdom and honour, your mincings and mouthings at the slightest shadows of indecency…that lofty esteem in which you hold yourself, and those pitying glances which you cast upon all, your frequent lectures and your acid censures on things which are pure and harmless; all this, if I may speak frankly to you, Madame, was blamed unanimously. What is the good, said they, of this modest mien and this prudent exterior, which is belied by all the rest? She says her prayers with the utmost exactness, but she beats her servants and pays them no wages. She displays great fervour in every place of devotion, but she paints and wishes to appear handsome. She covers the nudities in her pictures, but loves the reality. (p. 26)

Well, sacre bleu! Drop the mike! Célimène, like Alceste, seems to have her own gift for merciless anatomizing of the flaws of others. But what Célimène does not realize, at this point in the play, is that the wounded Arsinoé will have her own opportunities to repay Célimène’s unkindness in just the same sort of coin-of-the-realm that Célimène has been spending so freely.

Meanwhile, Alceste’s secure existence of smug, complacent, above-it-all misanthropy has started to fall apart. His maladroit servant Du Bois warns Alceste that, because of his earlier harsh criticism of Oronte’s poetry, “you are threatened with arrest”, and that “for your very life you must get away from this” (p. 42). It seems that giving a negative review to an aristocrat’s poetic effusions, in the France of these times, can have some serious consequences. Alceste’s subsequent reflections on human character and potential take on an even grimmer tone than usual, in spite of Philinte’s perfectly rational suggestion that “All human failings give us, in life, the means of exercising our philosophy” (p. 44).

As all of Célimène’s suitors gather, Arsinoé orchestrates the revelation of a series of letters in which Célimène has assured each of her suitors that he is “the one,” the favourite of her heart, while insulting, behind their backs, other suitors whom she has praised to their faces. This revelation leads to one final, scarring conversation between Alceste and Célimène, two misanthropes who are only too well-matched – and only Philinte and Éliante, as young people of good will who try to find a balance between respecting society’s conventions and being true to oneself, are left to offer some measure of hope for poor, despised humankind.

Molière played the misanthrope Alceste when The Misanthrope was first staged at Paris’s Théâtre du Palais-Royal in 1666, and it is interesting to wonder how the playwright may have found himself relating to this most famous of his characters. Molière had made a name for himself through unsparing depictions of the character flaws of people of his time; did he worry that the habit of doing so might ultimately make him an Alceste-like misanthrope, capable of seeing the faults of others while unable to see, or do anything about, his own flaws? Whatever the case might be, The Misanthrope remains a consistently funny play that, in the best tradition of classical comedy, addresses serious issues in a devastatingly perceptive way.