What do you think?

Rate this book

120 pages, Paperback

Published December 1, 2021

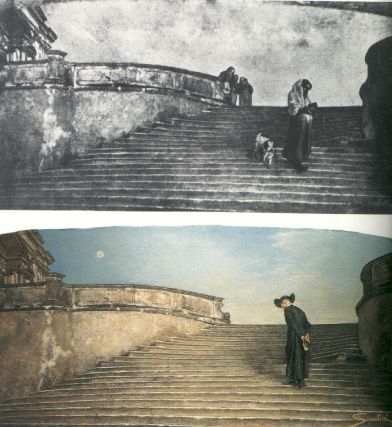

The manuscript, as I recall, concerned Herbert Spencer's claim to have invented the paper clip; Jean-Baptiste Rousseau's spat with Voltaire in a carriage ride through Brussels (I think it was) and Pascal's phobia of abysses, after his own gig nearly plummeted into the Seine; the actor Michel Simon's bohemian home in Noisy-le-Grand in the Paris outskirts, with its mesh tunnels through which pet monkeys roamed freely; Robert Walser's death in the thick snow on Christmas Day; Giovanni Segantini's painting of floating women; the psychoanalytic dispute on the nature of tics; Giacometti's tiny statues pocketed as he rode the night-train from Geneva to Paris after the war, and the inhuman grace of Kleist’s puppets; and Swiss ballooning.

Elisabeth sah ich in diesen Monaten nur ganz wenige Mal auf der Straße, einmal in einem Kaufladen und einmal in der Kunsthalle. Gewöhnlich war sie hübsch, doch nicht schön. Die Bewegungen ihrer überschlanken Gestalt hatten etwas Apartes, das sie meistens schmückte und auszeichnete, manchmal aber auch etwas übertrieben und unecht aussehen konnte. Schön, überaus schön war sie damals in der Kunsthalle. Sie sah mich nicht. Ich saß ausruhend beiseite und blätterte im Katalog. Sie stand in meiner Nähe vor einem großen Segantini und war ganz in das Bild versunken. Es stellte ein paar auf mageren Matten arbeitende Bauernmädchen dar, hinten die zackig jähen Berge, etwa an die Stockhorngruppe erinnernd, und darüber in einem kühlen, lichten Himmel eine unsäglich genial gemalte, elfenbeinfarbene Wolke. Sie frappierte auf den ersten Blick durch ihre seltsam geknäuelte, ineinandergedrehte Masse; man sah, sie war eben erst vom Winde geballt und geknetet und schickte sich nun an zu steigen und langsam fortzufliegen. Offenbar verstand Elisabeth diese Wolke, denn sie war ganz dem Anschauen hingegeben. Und wieder war ihre sonst verborgene Seele in ihr Gesicht getreten, lachte leise aus den vergrößerten Augen, machte den zu schmalen Mund kindlich weich und hatte die überkluge herbe Stirnfalte zwischen den Brauen geebnet. Die Schönheit und Wahrhaftigkeit eines großen Kunstwerkes zwang ihre Seele, selbst schön und wahrhaftig und unverhüllt sich darzustellen.

Ich saß still daneben, betrachtete die schöne Segantiniwolke und das schöne von ihr entzückte Mädchen. Dann fürchtete ich, sie möchte sich umwenden, mich sehen und anreden und ihre Schönheit wieder verlieren, und ich verließ den Saal schnell und leise.