What do you think?

Rate this book

196 pages, Paperback

First published March 1, 1998

“Perhaps chance and destiny are interdependent, in that the latter cannot be fulfilled without the casual intervention of the former. A craggy rock placed at a distance from the water will never be worn smooth”

“Myrtle is an interesting subject – in regard to the question as to whether fate or chance holds the upper hand. The ifs are numerous. If Beartrice had not shown an affection for her, would she not have vanished into the orphanage. What if Pompey Jones’s unfortunate arrangement of the tiger’s head had not ended Annie’s hope of motherhood? If old Mrs Hardy had woken that morning in a cheerful mood, would Myrtle have been required to follow George down to the town. Then there is the matter of his returning to Blackberty Lane by a different route than was usual. If the woman’s screams had echoed unheard in another street, what then”

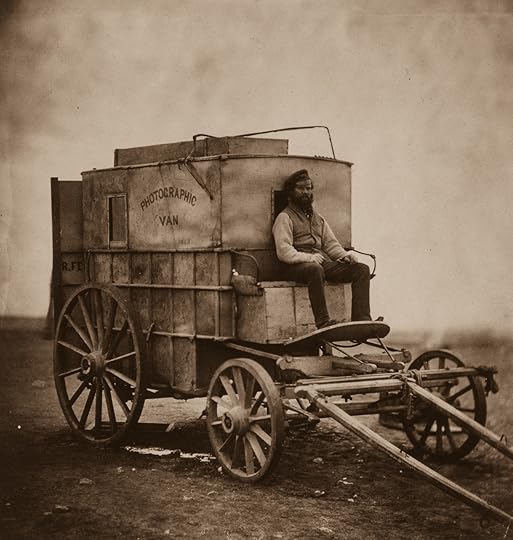

“There’s something of black magic in the photographer’s art, in that he stops time ….. I don’t know that I think much of the camera. It appears to hold reality hostage and yet fails to snap thoughts in the head … The lens is powerless to catch the interior turmoil boiling within the skull”

“I reckon memory is selective ….. I tried to get Potter to discuss what it meant when events were recollected differently. He said he wasn’t in the mood and had enough lapses of his own without fretting over other people’s”

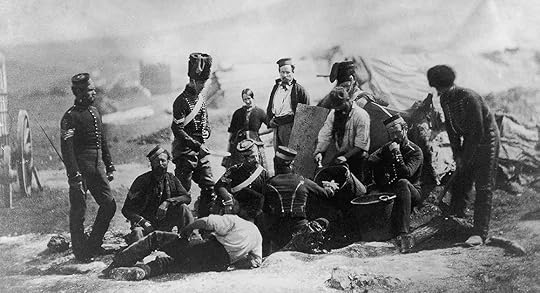

I engaged with a boy with a pimple at the corner of his mouth. He was clumsy with terror, flicking at me with his bayonet as though warding off bees. He shoulted something in a foreign tongue, and I said I was sorry but I didn't understand. I wanted to spare him, but he caught me a slash on my brow which got me cross and I jabbed him in the throat. He fell away, gurgling his reproach.Passages like the above (and they are legion) make me realize that my own title is misleading also. It is not that Bainbridge's individual images are blurred—they are replete with unexpected and precisely rendered detail—but that the exhibition that contains them lacks focus as a whole. I found this to be true also of her posthumous novel The Girl in the Polka Dot Dress, but I put that down to her inability to supervise the final version. However, I now gather that the vignette approach and almost willful refusal to labor a point are characteristic of her work at large. So read this for the detail, read it for its two magnificently self-inventing lower-class narrators, read it for the history—but know that any overall continuity will be up to you to infer.

Beryl Bainbridge said (possibly tongue in cheek), that most people needed to read this book three times before they understood it. Well I read it once, too quickly probably, and definitely feel I didn't understand it. Unless, of course, that is the point (which would be why Bainbridge might have had her tongue in her cheek).

Calling the six parts (chapters) of the book "plates" might be a clue. At the time in which the novel (novella?) is set, photography was in its infancy, and what we call "photographs" were then called "plates". The "plates" in the book were narrated/written/made/photographed by three different narrators, a technique which is always confusing, as, particularly in a novel this short, the reader is continually working out who says what, the relationships get differing perspectives and we frequently have to re-appraise both plot and perspectives.

One aspect that is unmissable is the horror of war and the shallowness and hypocrisy of 19th Century British colonialism. Which sounds like two things, except that they are connected. Colonialism was only possible through either threatened or, in most cases, actual violence. The depiction of war here holds no bars - it is graphic, bloody and shown to be every bit as gory, mechanical and inhuman as the "First World War" that it preceded. Colonialism is shown up as the murderous ego-trip of the rich few at the tragic expense of the poor, oppressed many.

Another element that struck me as important was that of chance and destiny. "Perhaps chance and destiny are interdependent, in that the latter cannot be fulfilled without the casual intervention of the former. A craggy rock placed at a distance from water will never be worn smooth." We can't help who we meet or often what effect that meeting will have on the rest of our lives.