Two human women, an octopus engineer, and a marginally-sentient fish named Jones eke a living aboard a light freighter across various interplanetary shipping lanes. Crate transport. Scavenger assignments. Curious quests to stay alive amid shifting sociopolitical loyalties. Times are tough.

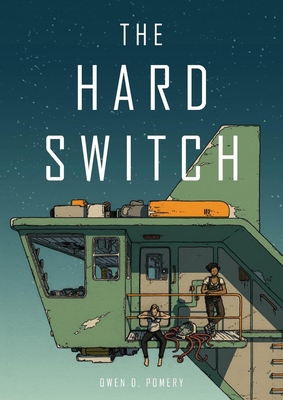

In THE HARD SWITCH, banal and expressionless characters push their way through a benevolently clever narrative premise whose promise loses its luster sooner than it should. The graphic novel's visual design, page composition, and coloring style are highly attractive and engender a relaxed, curious, and comfortable atmosphere. But the graphic novel's poor pacing, unremarkable character designs, and heavy reliance on dialogue nudges a tale of conflict concerning intergalactic immigration toward a meandering and unexceptional story about luckless freighters who regularly escape with their lives (for reasons left unexplained).

Ada and Hiaka guide their small-craft freighter here and there, scoring what they can to keep their meager lives going. Both have a good deal of experience under their belts; however, hauling junk for years on end will leave one with a few blind spots. Neither are immune to the temptation of a rare find, a newly discovered relic, or in Hiaka's case, traditional clothing sold by locals that looks too cool to pass up. The two are accompanied, primarily, by a pragmatic octopus, Mallic, the ship's engineer.

Such is the crew. Readers of THE HARD SWITCH will find little when it comes to discerning the attitudes and ambitions of the book's primary characters, but not for lack of trying. Ada and Hiaka aren't very distinguishable, in terms of personality, and the way they engage the primary plot point is debatable: Alcanite, a dwindling resource that powers interplanetary travel, is a good source of income for scavengers. But whether this group can actually scavenge up some alcanite is typically up to luck.

Much of the graphic novel teeters on plodding. Splinter plots concerning Ada's obsession with ancient markings on a random hunk of metal, an accidental scrap with interplanetary bureaucracy, and an unexpected visitor to the ship lend color and shape to Ada and Hiaka's adventures . . . but they don't necessarily bend the narrative in a way that's principally and confidently helpful. Alas, if the story hook is that all interplanetary travel is doomed when a certain finite resource goes dry, then why are readers wasting time on ship repair, negotiating bad-faith deals with fellow freighters, and more?

The crew faces lazy law enforcement officers, corrupt locals, and maleficent business operators, but at best, only a fraction of these events are remotely tangential to the primary story. THE HARD SWITCH isn't really about the upcoming "hard switch" from alcanite at all; the comic is about a handful of random encounters, of a small crew of freight pilots, who survive a few nuisance betrayals despite their own tediousness.

One loses energy hunting for the reasons. The dialogue is good, but the author clearly fell in love with their characters and couldn't figure out how to shut them up. The book's production design exhibits incredible detail and originality (e.g., off-world street markets, cockpit systems), but some panels are simply overloaded with dialogue. The book's lettering, on a related note, lacks grace. The font-size is painfully small, and since the author eschewed all font stylings of all kind (e.g., no bold, no italics, no changes in size or color), dinner arguments, explosive action scenes, and contemplative morning greetings all read the same: bland.

The lack of variability might also be crudely consigned to the comic's character design, but that's not fully the case. Stylistically, the book is clever and attractive. But upon further scrutiny, the lack distinguishing facial features means button-eyed characters look the same when they're angry as when they're happy. How excited is Ada to learn more about a potential alternative to alcanite that she heard of in old stories? Hard to say. How angry is Hiaka when their octopus engineer pal proffers a reasonable argument against bringing a stranger on board (e.g., fearing possible contamination)? Also hard to say. Lacking a dimensional nose, readable eyes, and functional eyebrows makes a huge difference.

THE HARD SWITCH takes place in an interesting universe, but the story readers encounter isn't itself all that interesting. The comic's First Act is slow, while the comic's Third Act is rushed and condensed; one feels put off, albeit not entirely surprised, when one encounters a regrettably familiar sci-fi scene in which one might ask the perilously eternal question: "Why do they have a switch for that on their ship?" THE HARD SWITCH is interesting, but only just so.