What do you think?

Rate this book

284 pages, Kindle Edition

First published March 15, 2022

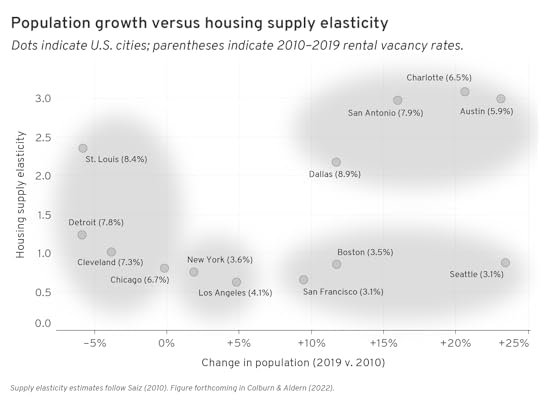

Ten friends decide to play a game of musical chairs and arrange ten chairs in a circle, A leader begins the game by turning on the music, and everyone begins to walk in a circle inside the chairs. The leader removes one chair, stops the music, and the ten friends scramble to find a spot to sit- leaving one person without a chair. The loser, Mike, was on crutches after spraining his ankle, given his condition, he was unable to move quickly to find a chair during the scramble that ensued. Pg. 13