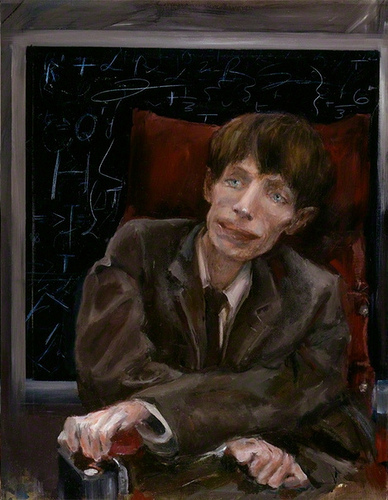

Stephen Hawking was one of the greatest scientists ever to live on this planet. He helped to completely change the realm of theoretical physics and ideas about the universe, and he did all of that while confined to a wheelchair for fifty years.

The book Stephen Hawking: A life in Science, written by Michael White and John Gribbin, could be described as half biography and half science textbook. What I mean by this is that the book would outline a part of Hawking’s life and then explain the science that he was working on at the time. The biographical chapters focused on Hawking’s personal life and academics, including the days of his youth, his marriage, his crippling disease, the books he wrote, and the movie he starred in that was based upon his book A Brief History of Time. It followed his life up until 1992, which is when this biography was written. In several sections, the authors did write about Hawking in the present tense because he was alive at the time of publication. The scientifical chapters focused on theories surrounding the beginnings of the universe and black holes, which were the main branches of science that Hawking studied. It also described the efforts to create a Grand Unified Theory that would be a set of equations that described every force in the universe including gravity, electromagnetic force, weak nuclear force, and strong nuclear force.

I found the book to be quite interesting and informative, although a little outdated. However, I doubt that people that are not very interested in science would like this book. A section that I found interesting was when they were describing the universe 0.1 seconds after the big bang. The book states, “The temperature was 30 billion degrees, and the Universe consisted of a mixture of very high energy radiation (photons) and material particles including neutrons, protons and electrons” (White 86). While not many people would find this interesting, I thought that it was fascinating that the universe had been so hot and that there weren’t even atoms at the time. However, some descriptions of Stephen Hawking were downright hilarious. At one point, the book states, “His favourite move, when he is annoyed by something someone has said, is to drive over their toes” (White 162). I found that it was hilarious that Hawking would use his wheelchair in such a manner and in fact his great regret, at least in 1992, is that “he’s not yet run over Margaret Thatcher” (White 162). This book uses colorful description effectively as shown by the previous example, but does not have much dialogue since the biography sections are written in a similar style to a documentary. There is a good reflection which talks about how Hawking became such a great scientist even though he had so many problems in his life. I would recommend this book to anybody that is interested in science and is looking for a lighter scientifical read that is mixed in with a biography of a major scientist. However, if you are not interested in science at all, this book might not be the right choice for you.