What do you think?

Rate this book

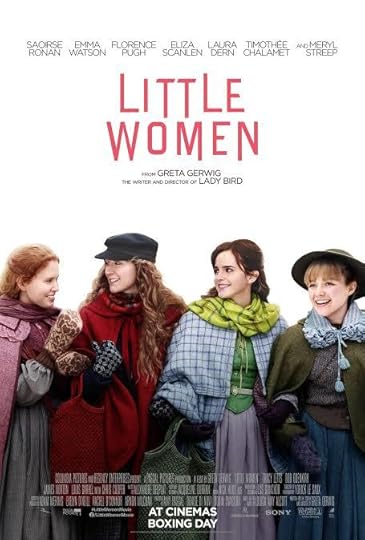

376 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1869

" He consoled himself for the seeming disloyalty by the thought that Jo's sister was almost the same as Jo herself, and the conviction that it would be impossible to love any other women but Amy so soon and so well"