What do you think?

Rate this book

444 pages, Hardcover

First published January 1, 2015

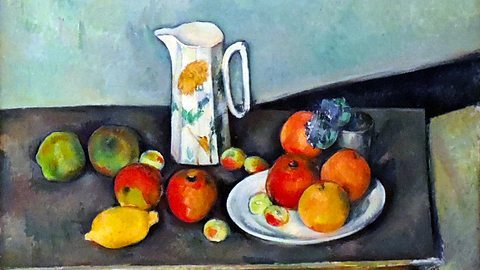

“French art in the nineteenth century was, in broadest terms, a struggle between colour and line.”

“It is a strangeness of Fantin’s considerable talent that his human portraits have the eerie, funereal look of still-lives; while his still-lives, the flower paintings by which he made his money (and also his name in this country), display all the vigour and life and colour of which he was inherently aware.”

“You don’t paint souls, you paint bodies, and the soul shines through.”

“Flaubert advised artists to be regular and ordinary in their lives, so that they might be violent and original in their work.”

“He [Redon] is also unusual in that he had his dark period first rather than last: he escaped the shadows, rather than feeling them close in with the years.”

“How far does an artist’s individuality develop as the result of pursuing and refining the strengths of his or her talent, and how much from avoiding the weaknesses?”

“A great painting compels the spectator into verbal response, despite our awareness that any such articulations will be mere echoes of what others have already put more cogently and more knowledgeably.”

“It doesn’t really matter whether an artist has a dull or an interesting life, except for promotional purposes.”

“Most Pop Art is art in a loose, trivial or jesting way. It is about hanging around art, trying on its clothes, telling us not to be overimpressed by it.”

“Art changes over time; what is art changes too. Objects intended for devotional, ritualistic or recreational use are recategorised by latecomers from another civilisation who no longer respond to these original purposes.”

“Most art is, of course, bad art; a large percentage of art nowadays is personal; and bad personal art is the worst of all.”

BOTW

BOTW http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b05zhhhy

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b05zhhhy 1/5: The Laughing Cavalier did not impress the young Julian Barnes

1/5: The Laughing Cavalier did not impress the young Julian Barnes

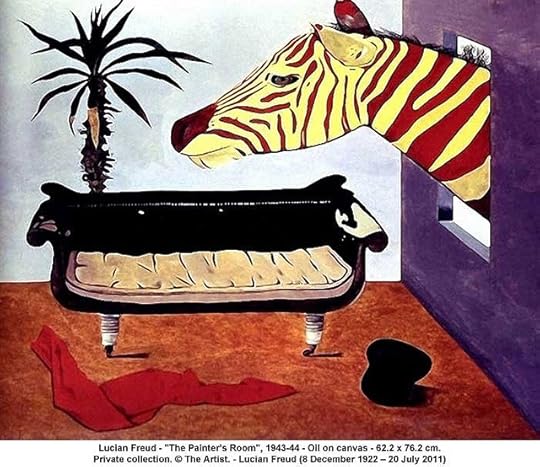

They are feet settling themselves in for useful work, like when a golfer shuffles for balance in a bunker. You can almost imagine the NCO's pre-execution pep-talk about the importance of getting comfortable, relaxing the feet, then the knees and the hips, pretending you're just out for a day's partridge or woodcock...."Fully illustrated in colour throughout" says the jacket flap. This is not true. The color illustrations (two or three per essay) are indeed of excellent quality and printed on thick creamy paper. But they tend to be details rather than the full picture, and often of works peripheral to the artist's more famous oeuvre. I understand the logic of that: Barnes gives you the things that are hard to find, knowing that you can turn to the internet for the rest. I found myself reading with iPad by my side, not only reminding myself of the masterpieces, but also seeking out things that I had never even heard of until Barnes mentioned them. For example Akseli Gallen-Kallela's "Symposium" (1894), "a Munchishly hallucinatory group portrait set at the Kämp Hotel in Helsinki after much drink has been taken." Interesting in that one of stupefied figures is the composer Jean Sibelius, but also because one side of the picture is taken up by "a pair of deep-red raptor's wings. The Mystery of Art has just called in on them, but is now flying away." Barnes' art criticism, like his stories, is full of unexpected trouvailles like that. But the heart of all his essays is his invocation of masterpiece after masterpiece, in words so full of visual detail that you almost do not need the physical reproductions. Almost, but not quite: for only when you look at the pictures do you realize just how right Barnes is, time after time.

"Cât timp petrecem cu un tablou reușit? Zece secunde? Treizeci? Două minute pline? Și-atunci, cât petrecem cu fiecare tablou reușit din expoziția cu aproximativ trei sute de exponate care a devenit norma unui artist important? Două minute per exponat ar duce la un total de zece ore (fără pauză de prânz, ceai sau toaletă)." (p.99)

’Ah, but is it art? That old, tediously repeated question whenever bricks are laid, beds disarranged, or lights go on and off. The artist, defensive, responds: "It's art because I'm an artist, and therefore what I do is art." ... We should always agree with the artist, whatever we think of their work. Art isn't, can't be a temple, from which the incompetent, the charlatan, the chancer and publicity-chaser should be excluded; art is more like a refugee camp, where most are queuing for water with a plastic jerry can in their hand. What we can say, though, as we face another interminable video loop of a tiny stretch of the artist's own unremarkable life, or a collaged wall of banal photographs, is, yes, of course it's art, of course you're an artist, and your intentions are serious, I'm sure, it's just that this is very low-level stuff; try giving it more thought, originality, craft imagination - interest, in a word.

...

What counts is the surviving object and our living response to it. The tests are simple: does it interest the eye, excite the brain, move the mind to reflection, and involve the heart; further, is an apparent level of skill involved? Much currently fashionable art bothers only the eye and briefly the brain; but it fails to engage the mind or the heart. It may, to use the old dichotomy, be beautiful, but it is rarely true to any significant depth. One of the constant pleasures of art is its ability to come at us from an unexpected angle and stop us short in wonder.’