What do you think?

Rate this book

448 pages, Paperback

First published May 23, 2017

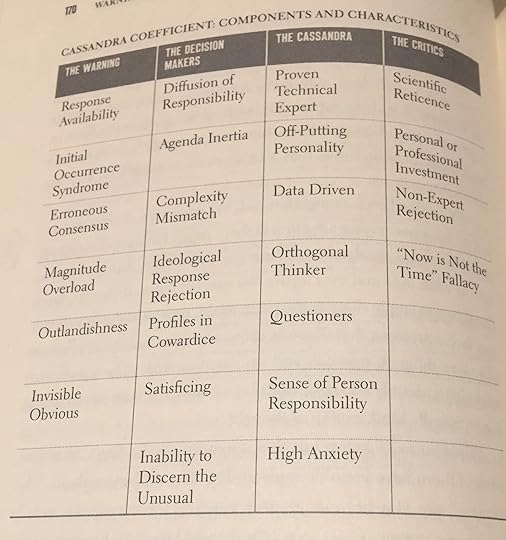

Knowing when the data is rich and extensive enough to trust it and when it is too scant is difficult. If data is in short supply, don’t worry about probability... Instead, focus on possibility. Is it possible? Could it happen?

One man with the truth constitutes a majority. —SAINT MAXIMUS THE CONFESSOR