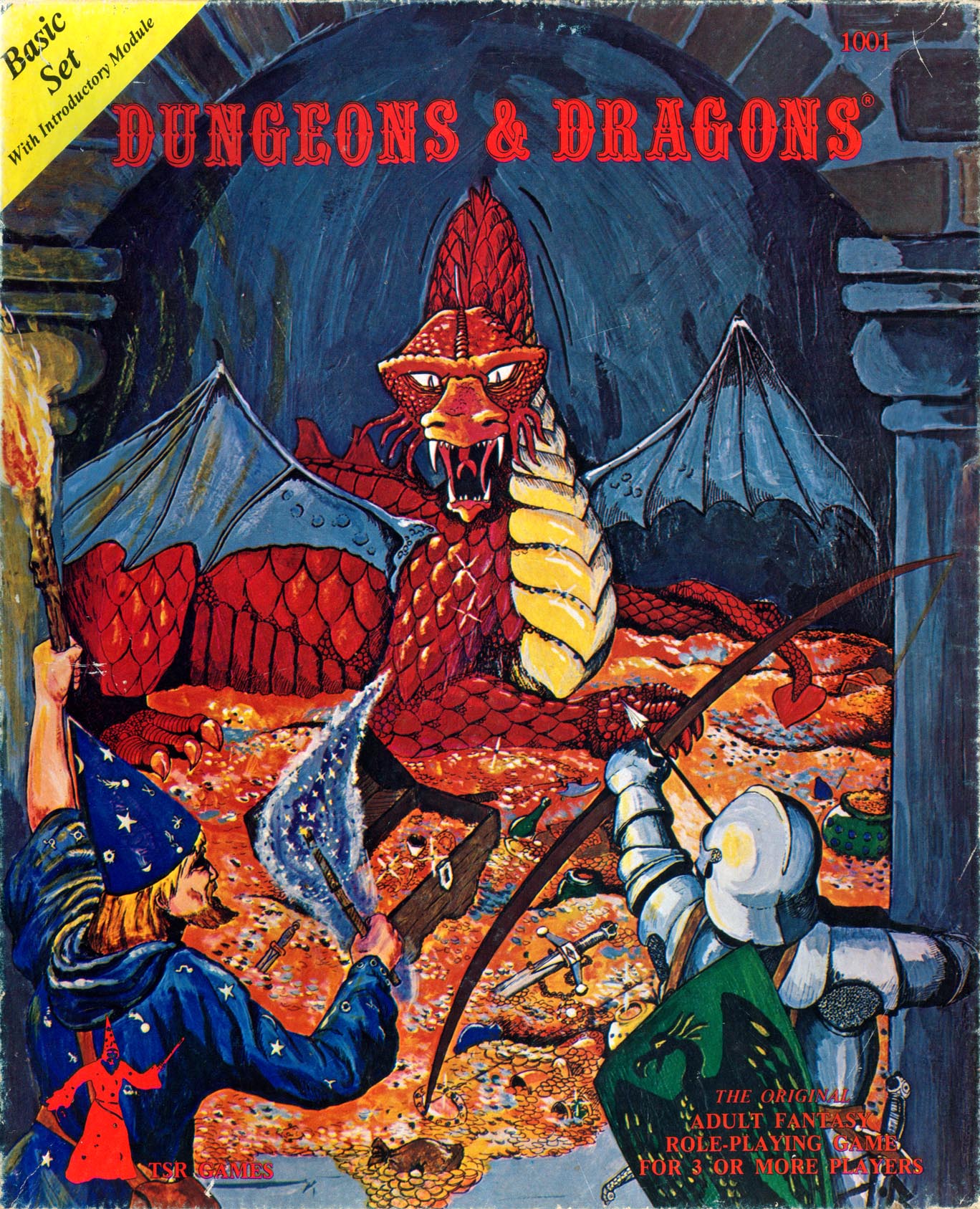

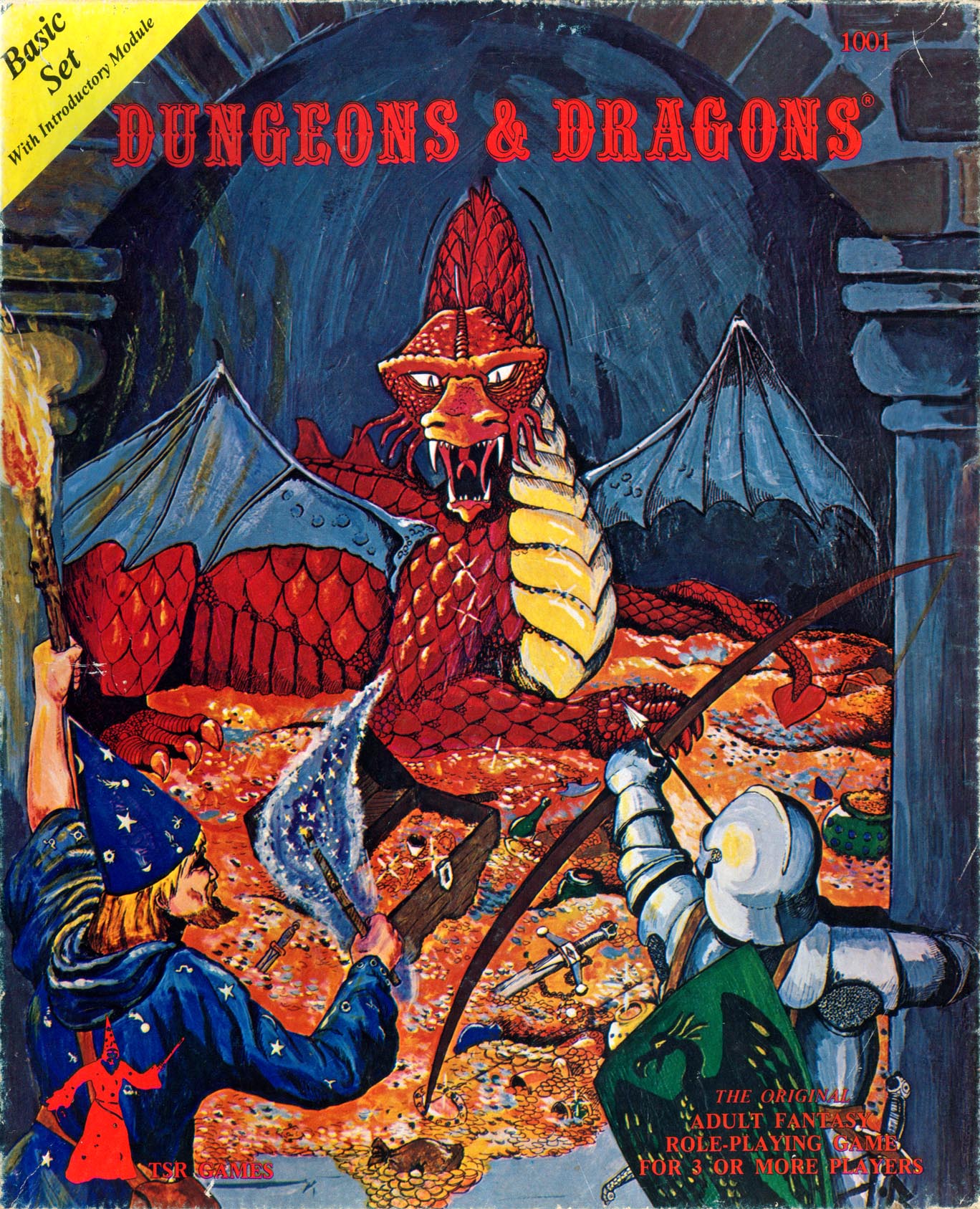

My copy of Eric Holmes’s 1979 edition of Dungeons & Dragons is the oldest book in my RPG collection. It was the first RPG I ever played. I was 7, possibly 8 years old, and my brother, 11 or 12, was the DM. Even though I played D&D with my brother over the next 10 years, I’m not sure I ever read the books before, and certainly never all the way through. We had the AD&D books before long, so the game we played was a mashup of rules, just like every other homebrewed game of D&D going on around the world.

Reading the book now was an enjoyable and interesting experience. I had always thought of the game as being about characters and adventures, but really it is a game about strategy and luck, or what I have been calling chance and choice. In a lot of ways, the game is like a board game, only the board gets revealed as the players play. Each encounter, or each dangerous room, reveals not what’s in the characters’ heads or hearts, but what is in the players’ heads, and occasionally I suppose in their hearts. The choices you make are not about “what would my character do,” but “what would I do to try to survive this.” This is especially true at lower levels when characters are fragile and prone to dying. Questions of motivation and relationships are all moot early on. We are here to get gold and to get stronger and more efficient! Any roleplaying about interpersonal friction is flavor on top, not a prescribed part of the game. From personal experience, I know that the longer you play in a campaign, the more relevant things like character and relationships become, but when you are in a dungeon proper, survival is always the foremost goal, and that’s about you the player, not the character your playing.

The heart of the game is randomization and probability. The rules of the game are essentially a list of probabilities for any given situation. Chances that a door are closed and locked, chances that a wandering monster comes by, chances that you are poisoned, chance that you hit with your sword, chances that you notice a secret door—it’s all a collection of probabilities. This is the backbone of the game’s “fairness” to some extent. It’s not the DM’s decision whether a monster comes along, or if it does what kind of monster it is. That’s the dice. It’s not the DM’s decision whether the noise you are making is going to bring danger on you. That’s the dice. In fact, in Holmes’s parting words, he says this: “You are sure to encounter situations not covered by these rules. Improvise. Agree on a probability that an event will occur and convert it to a die roll – roll the number and see what happens!” The very act of creating new rules is the act of determining probability.

But it’s not just chance; it’s choice too. The DM’s choices come in part before the game is played. The DM chooses what the dungeon looks like, where the traps are, where the monsters are, and where the treasures are. (The restrictions are made clear in the game too, though. Only a third of the rooms should be populated. Choose monsters that give a challenge but aren’t impossible. Create traps that are dangerous but capable of being overcome. Give enough treasure to reward their effort, but not so much that levelling up is simple.) Then, during play, the characters encounter the dungeon and your job is to play it out as it is by seeing what they do and having thing trigger as you set them. Of course, there are decisions the DM needs to make during play to, such as fictional positions that affects the odds as the rules present them, making this event more likely or that event less likely. The DM is kind of an arbiter of chance, but unless something is obviously impossible or un-fuckup-able, the dice will have the final word.

The players choices are about resource use. The stats may be random, but the player can sacrifice points from this stat to raise that stat. The money assigned may be random, but the player decides what items to get with her dearth or surplus of wealth. The hit points rolled may be random, but how fiercely I protect that number is up to the way I engage with the dangerous world of the dungeon. The tension of the game is between the greedy goals of the characters and their limited means in a world that places life and death pressures on them.

The capitalist bent of the game has been much discussed, but it’s really a festival of Darwinism, isn’t it? You are born from the random DNA of dice, but it’s up to you to make something of yourself. If your random collection of genes is good, your choices wise, and luck on your side at key moments, then you might be bound for greatness. But any one of those things being off can spell your doom. Wise choices with shit stats is a greater uphill battle. Great stats with careless playing will likely result in a fine-looking corpse. But life is cruel, and sometimes great stats and wise choices can still fail in the face of a single bad dice roll. There’s a fairness about it that is appealing to the American mind. Your character might be a fantasy version of an Horatio Alger’s story, an epic rags-to-riches tale of pluck, determination, and good choices. But it also says that just because you’re born with every advantage, it doesn’t mean you will succeed. The world (i.e. the dice) may be indifferent, but there is fairness and equality in that indifference. The characters are incredibly mobile, socially and financially, and barring death, they will only ever go up. It’s an American dream set in a fantasy world.

This is a beautiful edition of the game for its simplicity and completeness. Everything you need, including a sample dungeon, is in 48 pages. That includes an equipment list, a set of monsters, and a collection of spells. From there you can expand in anyway you like, making the laws of fate more exacting and specific, or further generalizing other possibilities. Holmes’s writing is clear and there are very few parts of the rules that require greater clarification. I’m undoubtedly influenced by the nostalgia of my youth, but this is a great way to play D&D.