The Gift Of A Radio – Justin Webb

If you were brought up without your real father, but knew his name and that he was alive, would you seek him out?

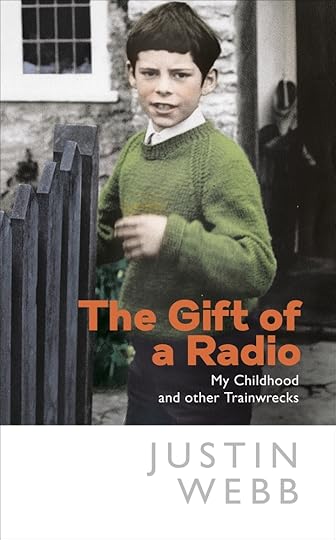

It’s a fascinating question, and one which features heavily in the childhood memoirs of BBC Radio 4 Today presenter Justin Webb. Brought up by his Quaker mother Gloria and stepfather, Charles, who she married two years after he was born, Justin Webb introduces us to his real father just seventeen pages in to The Gift Of A Radio. It’s a fleeting introduction. There he was watching the TV news presented by “a lugubrious looking chap with a deep plumy voice,” when his mother said – “That’s your father.” Justin Webb writes, “I don’t think I spoke.” His real father’s name is Peter Woods, a very familiar TV newsreader in the 1960‘s and 1970’s. And that’s that. “We hardly mentioned him again,” he writes. He adds that he’s not written his early autobiography to blame anyone, but that he’s to blame “for not asking the questions that demand answers decades later.”

Towards the end of the book, Justin Webb finds himself chosen as one of those lucky few who make it on to the BBC Graduate news trainee scheme. It’s not completely clear from his book whether his real father was also still working at the BBC when he joined, but he states “he had been retired for three years when I first walked into a TV newsroom.” It’s perfectly possible therefore that though they may not have worked in the same room in the BBC, they may well have been working for the corporation at the same time, before Justin Webb made it into the TV newsroom and was being trained in other departments.

It’s clearly something that haunts him. The last paragraph in his book begins, “Peter Woods and I never met.”

I cannot begin to try to understand his feelings towards his real father he never knew. However, presented with the facts he reveals in his book, I’m fascinated that a man who has become one of the nation’s chief inquisitors, never attempted to seek Peter Woods out. Journalists are naturally nosey, forever prying and probing into the affairs of others, and yet, despite hoping throughout the book that he has made contact with Peter Woods, it’s sad to think he never did.

I have some sympathy for Justin Webb, as my own father also lived his entire life, only seeing his real father on two or three occasions. My father was brought up by just his mother. He rarely talked about his father, never had the urge to go and visit him even though he had his address. I and my siblings never met him. My father only found out his father had died when a cheque for a small amount from his will arrived in the post. That lack of a relationship with his father led my father to have personal problems in his life, and I’m pretty sure affected the way he brought me and my siblings up. I could sense his feeling of sadness, of let down, of a refusal to put the past behind him and start afresh. However, that could have led to further rejection as it takes both parties to want to get together.

In Justin Webb’s case it’s sadder still to read of the absence of any loving relationship with his stepfather. In one episode, sitting on an English beach, he watches his stepfather Charles swim out to sea, and hopes he will never come back. Justin Webb writes that his stepfather had what would be described today as “a personality disorder.” He writes that Charles once confided to his mother that he could hear voices in his head. “He could not accept that anything anyone ever said or did in front of him, or to him, was anything other than part of a plot.” He would sit listening to Bach on the record player, sometimes at a very loud volume. Then there was the issue with supposed delusions of people getting into the family garage and fiddling with the oil or the windscreen wipers on the Hillman. It led Charles to replace the garage doors and even sleeping there. He writes, “Charles was becoming eccentric to the point of frightening.”

No wonder growing up in such an atmosphere gives Justin Webb a very depressed view of the decade in which he grew up – the 70’s. There are paragraphs on what he perceives to be the dismal state of Britain during that time – industrial strife, the three days week, the oil crisis etc.. There is nothing of the TV programmes, the music, the culture, the arrival of foreign holidays, the growing consumerism and affluence that children of his age were enjoying and realising that they’d really never had it so good.

The sense of this depression is worsened when he is carted off to private school, a Quaker school in Somerset. To those of us who went to state secondary moderns, it’s no surprise that Justin Webb went on to get onto the revered BBC news trainee scheme, which virtually exclusively year after year was reserved for former private school pupils who’d gone on to the top universities. I should know because after applying two years running, and getting one interview, I asked the BBC to send me details of the general education of the successful applicants. Despite being years before the Freedom of Information Act, they sent me a file showing year after year, ten of the twelve successful applicants recruited from Oxbridge. In his book though, Justin Webb tells the reader, “My private school life never felt privileged.....I would have yearned for actual privilege: for a home with parents and a life in a nice comprehensive.” Having been educated in a secondary modern which turned into a comprehensive, nice is not the word I would use to describe it!

Whether he feels his education was privileged or not, Justin Webb is quite graphic about the horror of the brutality metered out to boys at his private school. He writes of a twelve year old pupil discovered having gay sex in the changing rooms - “he was made to sit in the showers while boys cracked the top of his head with their knuckles until he cried. He adds he was chased and kicked, subjected to mental torture as well as physical - “He was a pariah at twelve. A leper at thirteen.” And then the sentence of tortured guilt –“he haunts me still because I did absolutely nothing to help him.”

Later in the chapter, he tells how the teachers and governors knew about the physical beatings going on, “but didn’t care.....there was no authority that could protect younger or vulnerable boys.” This is not the first account of the regime in private school and it won’t be the last. I’m pleased to read his view now about private education, which is identical to my own –“to send a child to live away from home at the age of eleven may be forgivable in some circumstances, but not in most.”

Justin Webb writes of feeling alone in the big wide world in which he was becoming an adult. Just him and his mother, with few friends. It’s therefore somewhat amazing that he has made such a success of his life and become one of the nation’s favourite broadcasters, at a time when his employer, the BBC, is recruiting it seems, anyone but privately educated, white, well spoken men.

He and I are about the same age, and I can identify with some of his experiences including, uncannily, a trip he made to Athens around the same time as me in the early eighties. He went with the Magic Bus company, I went with a similar operator but Greek – Theo Consolas. The fare was dirt cheap, you travelled more or less non stop with just a few minutes’ stop at emerging service stations, travelling across Europe including behind the Iron curtain into what was then Yugoslavia, arriving in Athens about four days later. Justin Webb’s memory of the drivers is something I share which has never left me and often relate to others. There were two coach drivers. When they changed shifts they didn’t stop the bus. As Justin Webb masterfully describes, “Grizzled driver would get the coach into fourth gear and lurch suddenly out of his seat while keeping one hand on the wheel. The coach was coasting along with no ability to brake. Fat Man would ease himself into the seat and grab the wheel, slightly correcting a course that was taking us into the middle of the road....the drivers did not sleep and did not eat.” I can vouch for every word because that’s exactly what happened on Theo Consolas’ coach. What didn’t happen to my coach is the incident Justin Webb goes on to describe and which I won’t reveal here, as it’s for you to discover if you read his book. All I will say is

he’s lucky to have survived!

As a regular listener of the Today programme, I now tune to Justin Webb with a renewed and added interest, knowing a lot about what has moulded him. It’s clear from his book that his childhood was not a happy one. To emerge sane from a home where there is mental illness is an achievement. I speak from personal experience. I congratulate him for being so honest and hope it may have been a cathartic experience to publicly reveal his sad start in life. One thing I feel for sure – his life’s experiences will help him as an interviewer as he comes across others who’ve been through similar hardship and he’ll have a more rounded view of the world in which very little, if anything, is perfect.