What do you think?

Rate this book

307 pages, Hardcover

First published April 11, 2023

If you don't like the weather, wait ten minutes and it'll change.Often said about Atlanta and about various other locales.

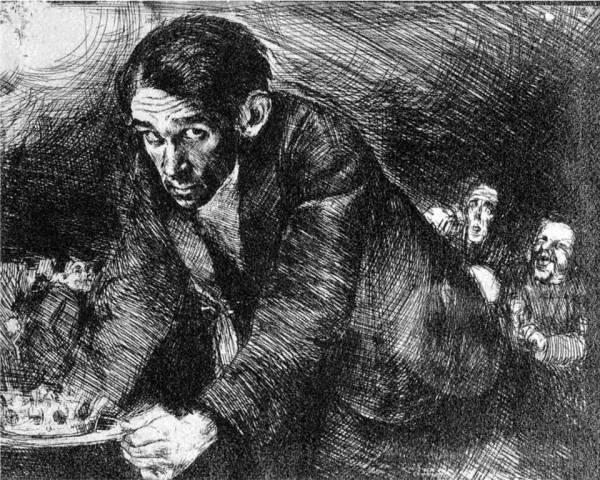

Schulz was born an Austrian, lived as a Pole, and died a Jew. His life began under the banner of the Austro-Hungarian double-headed eagle and ended in the genocidal dehumanization of Nazi occupation. Born a citizen of the Habsburg monarchy, Schulz would--without moving--become a subject of the West Ukrainian People's Republic (November 1918 to July 1919), the Second Polish Republic (1919 to 1939), the USSR (September 1939 to July 1940), and, finally, the Third Reich.

In Communist Poland, Jewish victims of the Nazis were tallied not as Jews but among the Polish victims of "The Great Patriotic War"; they were said to have been murdered not as members of a "race," as defined by the Nuremberg Laws, but as opponents of fascism. "The paradox of eight hundred years of Jewish presence in these lands," the Polish photographer Mikolaj Grynberg said of this conflation, "was that they were only allowed to be Poles once they were dead."

...rests on a simple predicate: Having mourned their dead, commemorated their martyrs, and rebuilt their shattered cities, the Polish people had recovered from the war: Polish Jews--and their thousand-year-old culture--had not. As far as Jews are concerned, Yad Vashem maintained, Poland is a wasteland. Thus the rescue of Schulz's fragments was nothing lessthan a step in the redemptive over coming of the Jews' exile and fragmentation. For Yad Vashem--concerned with Schulzl's death as a Jew rather than his life as an artist--those fragments are witnesses to the Shoah by one of its countless martyrs. (The Greek word for witness is martis, or martyr.)

Schulz scholar Andriy Pavlyshyn said, "Ukraine is not a literature-centric culture, unlike Poland and Russia,where they go crazy over hte written word.... In Ukraiine, even thke most inventive books sell hardly a thousand copies."

I have never been back to Drohobycz, and I don't want to. Wilek Tepper flew there to say good-bye and laid a plaque on one of those large graves in Bronica. And what happened? In broad daylight, people came with a bulldozer looking for gold and unearthed the bones.