In 1789, Thomas Jefferson remarked that “Democracy depends on an informed electorate.” Do we have that? Misinformation in mass media is a concern today and this book attempts to address it. The book’s thesis is based on a very weak analogy: misinformation is like a biological virus and can be neutralized by inoculation with the truth. That’s the sort of loose reasoning with undefined terms one expects in misinformation campaigns.

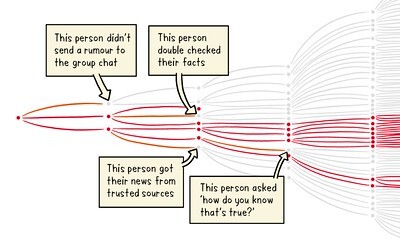

Scientific evidence demonstrates that some people are less persuaded by misinformation if they have been previously warned that some is coming their way, if they know the telltale markers of misinformation, and if they have contrary information to stand up against it. Such factors make up the so-called inoculation effect.

The size and significance of the claimed inoculation are not reported. This is not a scientific book and only vague and questionable summaries are given. Graphs are presented without scaled axes, categorical data are discussed as if they were continuous, and differences of less than one point on survey results are cited as important results. Such hand-waving makes all the author’s claims less credible.

Footnotes refer you to “Chapter Notes” in the back of the book, which in turn refer you to a bibliography, not a proper list of references. Of the many hundreds of entries in the bibliography, about half are articles in newspapers, magazines, popular books, and online websites. Of the peer-reviewed journals cited, most are general survey articles rather than reports of scientific results. Maybe that’s all a popular book needs to provide, but I would have appreciated more direct, solid, and accessible references for a book claiming to discriminate information from misinformation.

Throughout the text, terms are not defined, making the discussions and conclusions infuriatingly vague. The first third of the book emphasizes that “the brain” decides, judges, determines, is vulnerable, and is persuaded, as if it were a little homunculus in the head. “The person” is out of the picture, helpless and not responsible because “the brain” does all the thinking and believing. It’s utter nonsense, and I had little idea about what the first third of the book was trying to say.

True information versus misinformation are not defined, a rather serious omission for a book on this topic. If I say I have 2 pennies in my pocket right now, is that true or false? Information or misinformation? Ha! You don’t know, do you? Actually I don’t have any pennies. See how your brain is vulnerable to misinformation? But that’s not how these terms are properly used.

The author could have put a little effort into defining what he means by true facts, genuine information, misinformation. Likewise, what is a conspiracy? He gives lots of examples, such as that NASA faked the moon landing, but are there no legitimate conspiracy theories? The CIA really did conspire to overthrow governments in Iran and Chile. Those were conspiracy theories until they were proved true. Did Jeffrey Epstein really hang himself? In the absence of adequate information, conspiratorial explanations flourish. It doesn’t make them false just because they’re conspiracies. What’s missing is information.

I was not persuaded by the book’s main thesis that persuasion by misinformation can be meaningfully blocked with prior facts. Nevertheless, I did get some insights out of the book. One is that the people who control the sources of political and social information, mainly the government and large for-profit entities, don’t give out enough of it to thwart misinformation campaigns. It’s hard to argue anymore that tobacco does not cause cancer or that seat belts don’t save lives. But when the information is hoarded, misinformation flourishes.

I also realized that with the internet and social media “the electorate” that Thomas Jefferson was worried about has fractionated into thousands of micro-communities. That is a serious obstacle to the flow of information, and it facilitates misinformation.

The book also made me worry about the state of general education. People who think they can catch the flu from a flu vaccine don’t actually know what a vaccine is. The degree of ignorance about the basic facts of physical, social, and political life is frightening.

I think this book is well-intentioned but it came across to me as an exercise in persuasion using more than a little misinformation.

van der Linden, Sander (2023). Foolproof. New York: W.W. Norton, 358 pp.