Tsugaru, published in November 1944, offers a journey that delves deeply into the themes of cultural identity, family, class, and personal introspection. Far from being a simple travel narrative, Dazai Osamu’s work reflects a layered introspection that weaves folklore, nostalgia, and existential reflection into a cohesive exploration of both the self and society. Despite being written during a period of heavy wartime censorship in Japan, when literature was encouraged to promote national unity, Tsugaru retains an unfiltered intimacy, grounded in Dazai’s conflicted sense of belonging to the Tsugaru region and his existential longing to understand himself against this cultural and geographical backdrop.

The structure of Tsugaru is distinctive among Dazai’s works. Each chapter focuses on a different area within Tsugaru, creating a mosaic of regions that contribute to Dazai’s unique form of “geopsychological discovery.” This structure allows Dazai to explore each area as both a literal landscape and as a metaphor for parts of his psyche shaped by Tsugaru. The book draws on traditional Japanese travel writing or fudoki, regional chronicles that documented local resources and cultural specifics, dating back to the 8th century. In Tsugaru, however, Dazai goes beyond traditional fudoki to explore not only topography but also the emotional and psychological landscapes that have influenced his identity.

Dazai begins his journey with a striking lack of pretension. He dismisses any desire to offer “pseudospecialist pronouncements,” framing his journey as an act of “love” for Tsugaru- a love complicated by his relationship to the Tsushima family’s legacy. His goal is not to simply document Tsugaru’s landscapes but to understand how this harsh, unforgiving region has shaped him, both as a writer and as a member of the Tsushima family. The journey serves as both a homage to Tsugaru’s resilience and an introspective inquiry into Dazai’s complex identity, revealing how deeply intertwined his personal fate is with the land he once left behind.

The historical context of Japanese travel literature greatly informs Tsugaru. The Edo period saw an explosion in travel writing as restrictions eased and guides documenting local delicacies and famous spots gained popularity. Unlike this approach, Dazai’s narrative evokes a pre-modern perspective that emphasises local uniqueness, juxtaposing it against the Meiji era’s push toward national homogeneity. Dazai’s interest in folklore, which he began exploring in works like Shinshaku shokoku hanashi (1945) and Otogi-zōshi (1945), surfaces here, enriching his portrayal of Tsugaru with cultural details that both preserve and critique the region’s traditional values in the face of encroaching modernity.

Throughout Tsugaru, Dazai reflects on the tension between tradition and modernisation, which had placed immense pressure on rural Japan to adopt the same uniform identity promoted in urban centres. In embracing Tsugaru’s rugged landscape and the cultural eccentricities of its people, he indirectly critiques this push for homogeneity. This act of reclaiming regional identity, however, is not a nationalist stance; it is a deeply personal endeavour to reconcile his own roots within a rapidly modernising Japan. While Tsugaru does resonate with the series’ intent to bridge the gap between urban and rural Japan, Dazai’s motivations are intensely personal. The journey feels less about reconnecting readers to the countryside and more about grounding himself in the authenticity he finds lacking in Tokyo’s refined but impersonal culture.

This authenticity Dazai admires in Tsugaru’s people is evident in their rugged, honest, and proud nature. Dazai contrasts the “mediocrity” he finds comforting in Tsugaru with the societal pressure for cultural refinement he faces in Tokyo. The severe climate of Tsugaru, characterised by Siberian winds, harsh winters, and frequent floods, forges a community that is resilient, honest, and self-reliant. Dazai notes how this harshness has produced a culture that values modesty over pretension, aligning with his own desire for authenticity in a world that often feels superficial. This unfiltered nature of the Tsugaru people mirrors Dazai’s own sense of self, making Tsugaru not just a place he returns to but a symbol of an identity he seeks to reclaim.

A recurring figure in Tsugaru is the renowned haikai poet Matsuo Basho, who epitomised the concept of wabi- the aesthetic of simplicity and transience. Basho’s journey in Oku no hosomichi, a work that is considered one of the pinnacles of Japanese travel writing, provides a counterpoint to Dazai’s own journey. However, unlike Basho, who embraced the journey as an ongoing path and saw beauty in life’s ephemerality, Dazai’s journey is rooted in a desire to reconnect with his origins, to “return home” both physically and emotionally. This distinction is vital: while Basho’s travel led away from home in search of fleeting beauty, Dazai’s journey back to Tsugaru is a search for grounding and continuity amidst a life he often perceives as fractured and transient.

Dazai’s reflections are underscored by an awareness of mortality, a theme that permeates much of his writing. In Tsugaru, he contemplates the deaths of his contemporaries and the inevitability of his own, remarking how the region’s hardships have “fixed his fate.” This tone of fatalism extends to his exploration of class, as he reflects on his privileged position as a member of the Tsushima family. Despite his desire for equality, he recognises that his background inherently separates him from his childhood friends. For instance, Dazai notes how his friend T uses formal language, while he speaks casually- a subtle reminder of the social dynamics ingrained in their interactions since youth. This discomfort with his privileged status is part of the existential struggle that defines Dazai’s return to Tsugaru, where he seeks a place of belonging that transcends class.

A pivotal aspect of Dazai’s journey is his visit to his brother, with whom he shares a strained relationship due to the weight of family expectations. Despite his attempts to reconnect, he remains overshadowed by his brother’s role as the family’s patriarch. Through storytelling with his nieces and sister-in-law, however, Dazai carves out a sense of belonging. His tales of childhood become a medium through which he momentarily transcends social difference, reaffirming his connection to his family on his own terms. In these interactions, storytelling and literature become his tools for bridging gaps within his family, allowing him to reclaim his individuality and defy the rigid class structures that have long defined him.

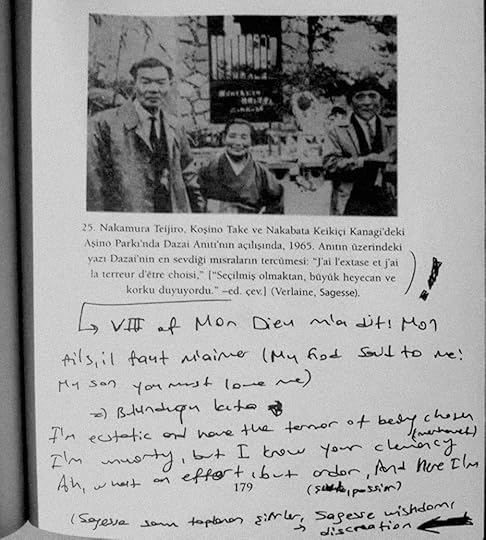

One of the most poignant moments in Tsugaru is Dazai’s search for his “missing mother,” embodied in his visit to Take, his childhood babysitter. This reunion is a central expression of furusato (hometown) as a space of maternal comfort and escape from individuality’s burdens. Dazai’s yearning for Take symbolises a deep-seated desire for emotional security, a “return to the mother” that psychoanalysts like Fromm and Funk might interpret as a yearning to merge with the mother figure to alleviate existential anxiety. This idealised reunion, however, is complicated by the reality of Take’s socio-economic status; her family, once independent farmers, became tenants of the Tsushima family due to mounting debts. Dazai’s memory romanticises their connection, while Take recalls him as detached, reminiscing with an acquaintance rather than truly connecting with her, highlighting the emotional chasm that still remains between them.

In Tsugaru, Dazai’s reflections on the theme of truth versus fabrication are integral to his narrative style. He openly admits to embellishing details, noting that “Recollections” contains “farcical fiction” yet remains emotionally truthful. Dazai’s belief that “reality consists in what you believe” underscores his narrative approach in Tsugaru, where fact and fiction blend to create an authentic portrayal of his subjective experiences. This candid mix of reality and fiction reflects his inner conflict, as he seeks a “true history of the subjective self” rather than an objective account. By doing so, he encourages readers to trust his emotional sincerity, even as he blurs the boundaries of truth.

In describing Dazai’s style, Reiko Abe Auestad notes that his “critical project” of self-exposure blends self-irony and vulnerability, creating a complex but genuine connection with his readers. This interactive aspect of Dazai’s narrative invites readers to become “co-conspirators” in his exploration of identity and selfhood. His concluding sentiment- “Art is me”- underscores the deeply personal nature of his work, framing his writing as a tool for navigating the complexities of his fragmented identity within both his familial and cultural context.

Ultimately, Tsugaru resists any simple conclusions. Dazai’s journey back to Tsugaru is not a return to wholeness but an exploration of the fluid and fractured nature of his identity. The land itself, with its unyielding climate and resilient people, mirrors the trials and resilience that define Dazai’s life. In Tsugaru, he captures the modernisation of Japan and its impact on rural identity while confronting the limitations of individual autonomy within the confines of family, class, and cultural expectation. In this narrative, Dazai transcends the personal and touches upon a universal search for belonging, ultimately revealing that identity- like Tsugaru’s rugged landscape- is shaped by both beauty and hardship, grounding him in a place that is as much a part of him as he is a part of it.