What do you think?

Rate this book

100 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 160

All this, however, with regard to style and composition, may be borne with, but when they misinform us about places, and make mistakes, not of a few leagues, but whole day’s journeys, what shall we say to such historians? One of them, who never, we may suppose, so much as conversed with a Syrian, or picked up anything concerning them in the barbers’ shop, when he speaks of Europus, tells us, "it is situated in Mesopotamia, two days’ journey from Euphrates, and was built by the Edessenes.” Not content with this, the same noble writer has taken away my poor country, Samosata, and carried it off, tower, bulwarks, and all, to Mesopotamia.

[The historian,] though he may have private enmity against any man, will esteem the public welfare of more consequence to him, and will prefer truth to resentment; and, on the other hand, be he ever so fond of any man, will not spare him when he is in the wrong; for this, as I before observed, is the most essential thing in history, to sacrifice to truth alone, and cast away all care for everything else. The great universal rule and standard is, to have regard not to those who read now, but to those who are to peruse our works hereafter.

Recollect the story of the Cnidian architect, when he built the tower in Pharos, where the fire is kindled to prevent mariners from running on the dangerous rocks of Parætonia, that most noble and most beautiful of all works; he carved his own name on a part of the rock on the inside, then covered it over with mortar, and inscribed on it the name of the reigning sovereign: well knowing that, as it afterwards happened, in a short space of time these letters would drop off with the mortar, and discover under it this inscription: “Sostratus the Cnidian, son of Dexiphanes, to those gods who preserve the mariner.” Thus had he regard not to the times he lived in, not to his own short existence, but to the present period, and to all future ages, even as long as his tower shall stand, and his art remain upon earth.

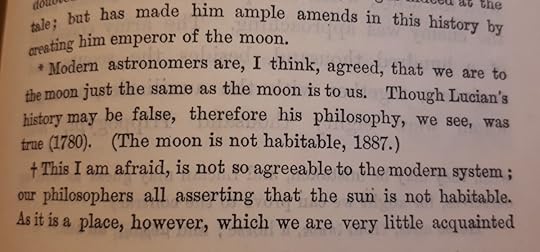

Know ye, therefore, that I am going to write about what I never saw myself, nor experienced, nor so much as heard from anybody else, and, what is more, of such things as neither are, nor ever can be. I give my readers warning, therefore, not to believe me.

Behind these stood ten thousand Caulomycetes, heavy-armed soldiers, who fight hand to hand; so called because they use shields made of mushrooms, and spears of the stalks of asparagus. Near them were placed the Cynobalani, about five thousand, who were send by the inhabitants of Sirius: these were men with dog's heads, and mounted upon winged acorns...