What do you think?

Rate this book

480 pages, Paperback

First published March 31, 2022

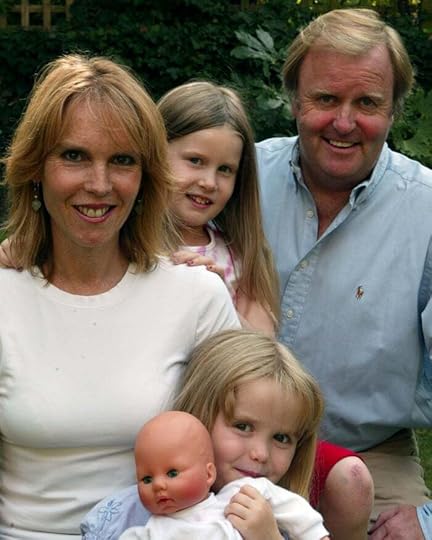

It was a stupid idea. The book was too advanced for her; too advanced, she was sure, for a student of science. But she was trying, at least trying, to understand what was happening to her daughter's body.

Anthracycline, antibiotics.

The problem with it was the lack of story. Narrative. When asked for his definition of Neighbour, Jesus did not turn to his glossary. He had a parable and a Samaritan up his sleeve. Human example is everything, thought Anne, as her hands shaped and carved and built and bent through pathology and insulin and enzyme activity and junctions and ecosystems.

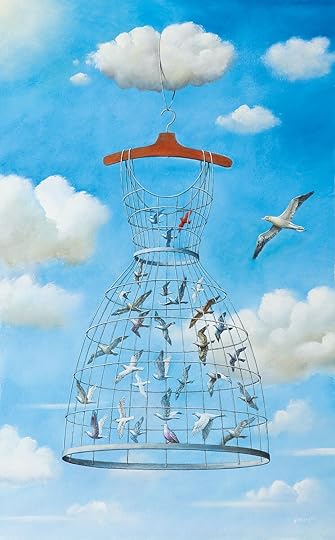

“There are three narrative threads in the book that are not only in constant communication, but are actively competing against one another to ‘tell’ the story. The events happening in Lia’s past and present are mapped onto the landscape of her body, the first person eats away at the third, there are fragments of anatomical science and religious philosophy, of poetry, painting and dance and typographic moments where words drip, or swell, as if magnified — they mirror and bend. By experimenting with form like this, by shifting between styles and building up patterns to pick at and unravel I found that the novel had become about the very act of storytelling; about the way we choose to frame our lives, and which version of ourselves we let take the lead. As Lia (an illustrator with a vast imagination) nears death, she is attempting to make sense of her choices, her illness. The piecing together of self is her final creative act.”

for all the play and ‘fizz’ there were also simple delights that emerged unexpectedly along the way. I learnt that a fully realised character or frank, honest dialogue can be just as poetic as a perfectly constructed metaphor, or a bit of clever word play. This, I think, is growing up. It’s realising that you have nothing to prove. It’s leaving your coat and scarf and pretension in the hall, taking the hands of your characters, and letting them lead you through the house.

“It is a shame, such a shame, Harry thought, that to be a human is to be one thing, to be

contained, to have these walls of skin and a singular sense of self that sloshes and slaps around inside of us like water on the inside of a well.”

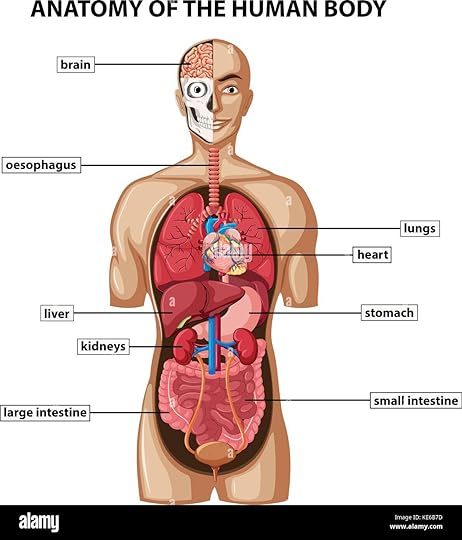

Whilst Maps of Our Spectacular Bodies is, at its heart, a family drama — it is also a formally ambitious novel. There are three narrative threads in the book that are not only in constant communication, but are actively competing against one another to ‘tell’ the story. The events happening in Lia’s past and present are mapped onto the landscape of her body, the first person eats away at the third, there are fragments of anatomical science and religious philosophy, of poetry, painting and dance and typographic moments where words drip, or swell, as if magnified — they mirror and bend. By experimenting with form like this, by shifting between styles and building up patterns to pick at and unravel I found that the novel had become about the very act of storytelling; about the way we choose to frame our lives, and which version of ourselves we let take the lead. As Lia (an illustrator with a vast imagination) nears death, she is attempting to make sense of her choices, her illness. The piecing together of self is her final creative act.