7/10

I sucked this book with great pleasure, despite the heavy content and the constant awareness that I was reading the first person account of someone's struggle with life.

Kabi Nagata is a Japanese mangaka, now in her early 30's. She seems not particularly gifted with creating fictional stories. At least that's what she says, and the manga industry seems to agree, as I think she has not managed to publish any fictional comic yet. Nonetheless, she has become a small sensation in her country - with usual echoes in Western comics niches - drawing about her real life. According to the info I gather from this book, which is her fourth memoir, her previous three manga were about her long list of problems: depression, eating disorders, inability to communicate, loneliness, health issues, sexual identity, lack of romantic life. I have not read those previous books, maybe for the best, because it sounds like they could strike home a bit too much in some aspects. Also, they are all in pink, and that colour bores me quickly. But this book is in orange, my favourite colour! Plus, it speaks of health problems different from the one that I have/had in my life. I gave it a try.

So, Kabi had never drunk alcohol until she was 28 year old. ('I thought I did not deserve to have a drink' she states in one of the most mysterious passages of her confession.) Then, in between the age of 28 and 31, she becomes a record-making alcoholic, ruining her liver and pancreas as much as other compulsive drinkers achieve in at least ten years - her doctor's claim, not mine. The memoir starts summing up the mental state that pushed her down this spiral. Then it focuses on her three weeks of hospitalisation for 'severe acute pancreatitis' and the following months of rehabilitation.

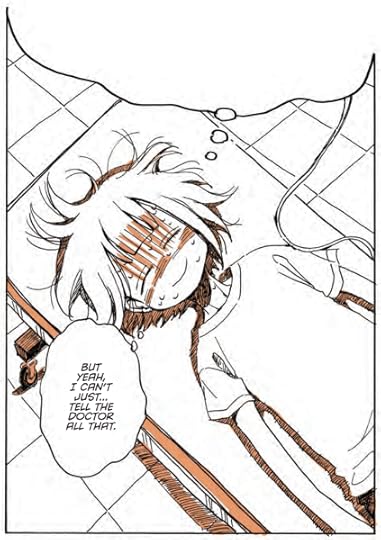

Mostly, she draws herself in a hospital bed or at her drawing table in her parents's house. Sometimes agonising with aches, sometimes agonising with depressive thoughts. But always thinking. This is a book about great painful reflexions and small realisations. In the most recurrent kind of panels she is seen from above, raising her head to the ceiling in the act of realising things about her existence. Most often bad things, but thankfully not always.

An important theme of the story is acceptance of irreversible changes. In the author's case, the fact that she will be a patient for her entire life. With the exception of a couple of painful and powerful panels, this theme is treated almost lightly, depicting how concretely Nagata learns to adjust to a low-fat diet and less drinking. (She does not completely stop drinking though, because this is real life, kids.)

In general, the portrait of Kabi Nagata that we obtain should belong to a therapist rather than us. Firstly, we have the longstanding deep rooted trauma: Kabi is a forgotten loner, to whom the surrounding environment has rarely paid attention or given love, since she was a kid. Then, the more recent trauma: Kabi is a daughter crushed by the guilt of having hurt her parents by displaying their family troubles in the previous memoirs. This guilt is somehow the engine that moves the story: the sense of guilt pushes Nagata to devote herself to pure fiction; the difficulty of writing good fiction pushes her to obsessively drink day and night; the drinking puts her in the hospital; the physical pain reinforces her guilt for making the family worry and not being able to produce manga. On top of all of that, we also have the (expected) Japanese self-flagellation for not being able to constantly produce an absurd amount of work. Indeed, her depression deepens when she notice that that she has not produced any publishable manga in four months. Actually three months, if we consider that one was spent basically dying in a hospital. This is the hard part to believe for a Westerner. Or at least for me. Everyone who has ever tried to create a comic story - actually everyone who has ever created anything - knows what a ridiculous magic wishful thinking is the idea of creating interesting stuff in only three months. (Well, everyone except Japanese people, apparently.)

The book ends with positive realisations. Somehow obvious realisations. But then again, when you struggle with your own demons, the obvious things can be the hardest to recognise and accept.

Nagata's approach to storytelling is simple and direct. The narration flows smoothly. The tender, yet never mawkish, art prevents it from becoming dry.

Pleasant reading. Maybe I will consider one day giving a look at her 'pink' books too.