What do you think?

Rate this book

535 pages, Kindle Edition

First published January 1, 1971

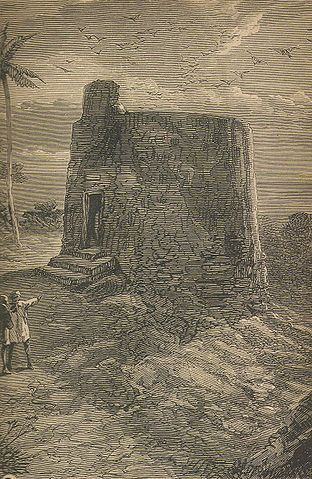

In September 1939, when the war had just begun, Miss Batchelor retired from her post as superintendent of the Protestant mission schools in the city of Ranpur.Paul Scott opens the third volume of his magisterial Raj Quartet, with a loquacious, well-meaning, but ineffective retired school teacher with nowhere to go. In reviewing the first volume of the Quartet, The Jewel in the Crown, I remarked on what I called Scott's liminal viewpoint, his tendency to tell the story of the last days of British rule in India through people who are relatively peripheral to it. This volume takes this almost to extremes, in focusing on a character with no power whatsoever. Barbie Batchelor is not a new arrival; we have met her already in the second volume, The Day of the Scorpion, and know that she takes a room in Rose Cottage, the house of the elderly Mabel Layton in the fictional hill town of Pankot. Indeed, with very few exceptions, all the action in The Towers of Silence has already been told in The Day of the Scorpion. It makes for a very peculiar book indeed, and not an entirely satisfying one.

Her elevation to superintendent had come towards the end of her career in the early part of 1938. At the time she knew it was a sop but tackled the job with her characteristic application to every trivial detail, which meant that her successor, a Miss Jolley, would have her work cut out untangling some of the confusion Miss Batchelor usually managed to leave behind, like clues to the direction taken by the cheery and indefatigable leader of a paper chase whose ultimate destination was not clear to anybody, including herself.

Looking at Sarah, Barbie felt she understood a little of the sense the girl might have of having no clearly defined world to inhabit, but one poised between the old for which she had been prepared, but which seemed to be dying, and the new for which she had not been prepared at all. Young, fresh, and intelligent, all the patterns to which she had been trained to conform were fading, and she was already conscious just from chance or casual encounter of the gulf between herself and the person she would have been if she had never come back to India: the kind of person she 'really was.'

The girl came the following morning. She said, 'The birds belong to the towers of silence. For the Ranpur Parsees.'