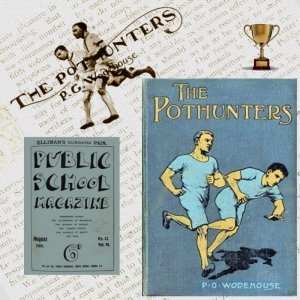

This is Wodehouse's first book, a pippin of an idyll of Edwardian public school life, and one that still glows with sunshine and inconsequence, lo these hundred years. More a set of sketches than a proper tale, The Pothunters ostensibly recounts the search for a sackful of school sporting trophies ('pots') that are burgled from the campus of St. Austin's, the first of Wodehouse's fictional boys' schools, each of which seems to exist on the banks of the river time in some changeless pastoral sward of England. While much fun is had lampooning the chase -- "the news continuing to circulate, by the end of morning school it was generally known that a gang of desperadoes, numbering at least a hundred, had taken the Pavilion down, brick by brick, till only the foundations were left standing, and had gone off with every jot and tittle of the unfortunately placed Sports prizes" -- the real business here is conjuring up the old school and idling about its parks and environs, following sundry dayboys and boarders as they gossip about their fellows, print up clandestine newspapers, roam the forbidden woods of a local MP in search of rooks and water-wagtails, fancy themselves detectives, nip out of their dorms after lockup for the rush of the illicit evening air, and generally drift, glide, and amble through 'the six years of unbroken bliss' that Wodehouse later christened his schooldays. A perk for the modern reader is that there is mercifully little of the cricket which will dominate A Prefect's Uncle, The Gold Bat, and ultimately Mike, Wodehouse's favorite among his own books; another is the absence of an Uncle Fred or Psmith to turn the book into a stagy cinematic mishmash of soliloquies and capers, and indeed the lack of any dominant character or fast-tracked plot at all that would distract from the aura of the place. (The resident pleonastic know-it-all is a student named Charteris, whom I actually prefer to Psmith: he doesn't bogart his scenes and is much less artificial.) So innocent is this departed world that I couldn't help delighting in the Rev. Herbert Perceval, headmaster of St. Austin's, who is sincerely scandalized when a visiting amateur photographer asks him if he spends his time off in the village neighboring the school. (Perish the thought!)

Like most of Wodehouse's youthful school stories, The Pothunters has been largely forgotten -- left to collectors, concordists, and the otherwise Plum-drunk, on whose shelves it musts and molders toward its estate sale consummation -- but much of the appeal of the book, at least to me, is in seeing how accomplished a stylist the 20 (!) year old Wodehouse already was. Too many people read this book impatiently, managing half a chapter while wondering when the hell that droll, omniscient butler** is going to show up, but why not take this for what it is, and in the meantime wonder how the narration is already this tight and the dialogue this crisp. The Pothunters obviously doesn't rival, say, the later works of Saki and Waugh for conceit and inspiration, but it shows Wodehouse already surpassing them for clarity and poise with his wonderfully modest and unprepossessing early style; Wodehouse's immediate acclamation, on the strength of just these few serialized school stories, was no caprice.

[** I know Jeeves isn't a butler, I'm just teasing the casual Wodehouse buffs.]

While no one who has read any of Wodehouse's books from the 20's on is going to be amazed by the banter or the turns of phrase found here, it is a treat to see glimpses of the familiar Wodehouse: already in bloom are the Biblical whimsies ("from east and west, and north and south, from Dan even unto Bersheeba, the representatives of the public schools had assembled"), the sullied Shakespeare ("how sweet the moonlight sleeps on yonder haystack"), the forgotten saws ("like somebody's something, it is both grateful and comforting"), and the sighs of put-upon benevolence ("the Head was a man who tried his very hardest to like each and all of his fellow-creatures, but he felt bound to admit that he liked most people a great, a very great, deal better than he liked the gentleman who had just sent in his card"). Another marvel is how few, how neat, and how accordingly welcome the perfunctory narrative jabs are ("Reade was deep in a book, though not so deep as he would have liked the casual observer to fancy him to be") - Wodehouse was a natural. Some of the scenes are similarly excellent: my favorite is the scene in which Roberts, the bored detective sent up from Scotland Yard to investigate the theft, casually amazes the blundersome Mr. Thompson, an unrequited sleuth, who, in the throes of "the detective fever", has taken it upon himself to crack the case ("Mr Thompson had once detected a piece of cribbing, when correcting some Latin proses for the master of the Lower Third, solely by the exercise of his powers of observation, and he had never forgotten it. He burned to add another scalp to his collection, and this Pavilion burglary seemed peculiarly suited to his talents.")

Having said all this, don't make this the first, or even the fifteenth, Wodehouse book that you read: start with the young masterpieces (Carry On Jeeves, Summer Lightning, the revised Love Among the Chickens), work your way through the glory years, and return to the early work when you're smitten with Plum. This isn't a good enough book to recommend to any reader, though it has to be one of the crowning English school stories (oddly enough, I prefer it and a few others to Mike): much of its charm now depends on an acquaintance with Wodehouse and a fondness for Bertie Wooster's schooldays. But if you like Wodehouse, or just the shimmers of a bygone world, this is one for your library list.

Rating (my Goodreads scale): *** - worth reading if you like the author or the period

Rating (my Wodehouse scale): 6/10

Time to read: 90-120 minutes