What do you think?

Rate this book

320 pages, Hardcover

First published October 1, 2006

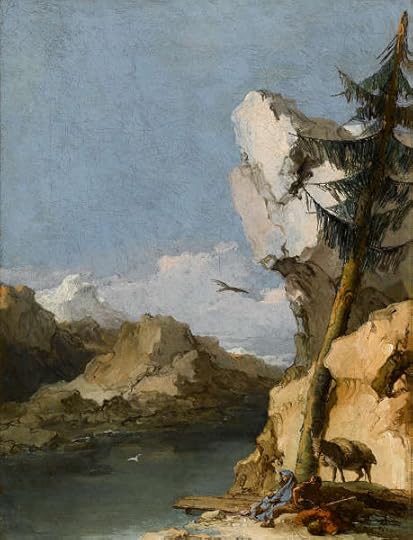

For Proust, Tiepolo was first and foremost Odette’s robes. In the eyes of this very young and stubborn worshipper, none of the outfits with which Madame Swann appeared in society were remotely comparable to the “marvelous robe in crepe de Chine or silk, old rose, cherry, Tiepolo pink, white, mauve, green, red, yellow, plain or patterned, with which Madame Swann had eaten breakfast and was about to take off.”Reading Tiepolo Pink conjures images of sitting in a comfortable, plush chair opposite of Roberto Calasso as we finish off a few bottles of exceptional wine. The whole time my transfixed awe of his monologue on Giambattista Tiepolo is probably much like that of Wallace Shawn in the movie My Dinner with Andre. Calasso goes off on seemingly wild tangents—ranging as wide as references to figures from antiquity and the Old Testament to Milan Kundera and Alfred Hitchcock—only to come back to with captivating, convincing, illuminating arguments about Tiepolo’s art. My only regret, considering the wonderful the language of the English translation, is that I’m not able to read it in the original Italian. His prose flows like a mesmerizing stream; much like a great rock song, you just want the jam going to keep on.

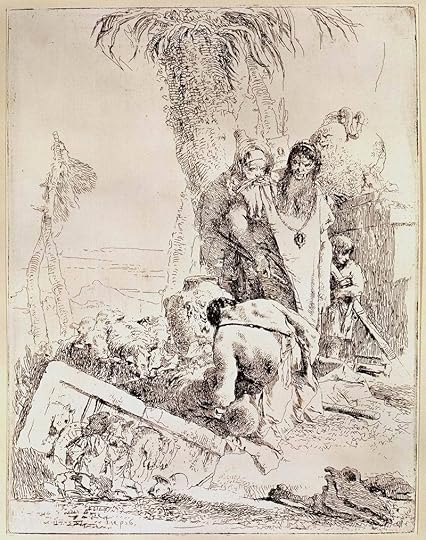

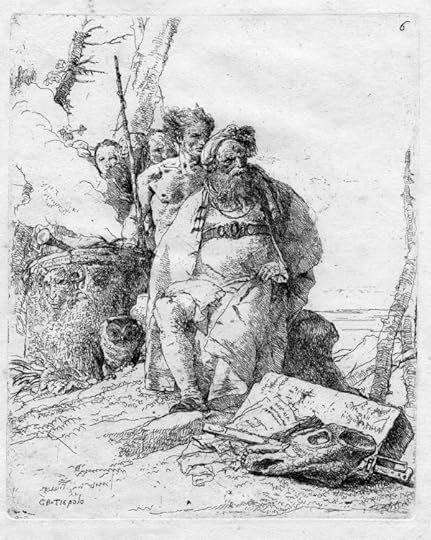

And what do the characters in Tiepolo’s Scherzi see? What are they pointing at? Not just what appears: the ashes, the snakes, the bones. But something else, which is not admitted, which has no name. In them there already resounds the baritone voice that Joseph de Maistre was to give to the senator of St. Petersburg as he says: “I have read millions of witticisms about the ignorance of the ancients who saw spirits everywhere: it seems to me that we who see them nowhere are much more foolish.”“In the Scherzi,” writes Calasso, “Tiepolo wove the countermelody to the Enlightenment. No one else would have succeeded in calling that up.” He places the observers in his painting, the “Orientals,” in the center of events in the Scherzi. The repeated images of staffs with snakes coiled around them refer back to both pagan lore and the Old Testament. For example, the story of Moses’s rod changing to a serpent “is like a dialogue between a magician and an apprentice.” Many parts of the Scherzi found their way into his greatest work, the ceiling frescoes in the Würzburg Residenz.

Tatarottti mentioned in his book that “in Erbipoli [the Italian name for Würzburg]…in little more than two years, between 1627 and 1629, one hundred fifty witches and warlocks, including fourteen Curates, and five Canons, were decapitated and burned.” Nor were these solely stories from the past. Again in Würzburg, just one year before Tiepolo’s departure (and hence in 1749), one of the last witches in Europe was decapitated and burned. Her name was Marie Renata Singerin, and she had been “convinced since childhood of having had relations with the Devil and of having succeeded in concealing such wickedness until the age of seventy-three years.”Tiepolo’s interpretations of America, Africa and Asia are among his most ambitious works. His view of Europe is more sedate, perhaps even a bit boring when contrasted with the other three continents, but one observer stands out.

The individual’s name is unimportant. Because he is the West, the only entity curious and foolhardy enough to get into trouble in such a faraway place—and always convinced that there are good business deals to be done. No one else saw this with Tiepolo’s prophetic irony. So prophetic indeed that it went unnoticed.As Europeans went on to plunder those parts of the world to build their wealth, Calasso praises Tiepolo’s prescience as “the most reliable portrait of a civilization.”

"A myth is the 'mesh' of a 'spider's web', and not a dictionary entry," Marcel Mauss once said. Tiepolo treated the stories his patrons asked him to translate into images in the same way. Christian or pagan—it was indifferent. Real or fictitious, at a certain point all events had to be transformed into the threads of the spider's web, hanging between the branches of a slanted tree trunk and swaying gently at every puff of wind. Never had it been possible to move around in the past with such agility, as if distances in tie and space were rhetorical arguments that facilitated contact rather than hindered it. The exotic, as such, no longer existed. All was exotic—or nothing.