What do you think?

Rate this book

63 pages, Paperback

First published October 10, 2009

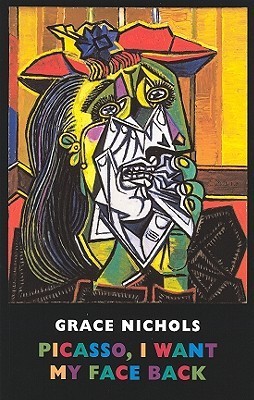

- Weeping Woman, 1, pg.

- Van Gogh, pg. 32

- Munch's Scream, pg. 39

O England

Hedge-bound as Larkin

Omnivorous as Shakespeare.

[from 'Outward from Hull']

I'd previously encountered the 'Weeping Woman' poem for which the collection is named, though couldn't recall where: it may have been when it was Poem of the Week in the Guardian, in December 2009. The poem-sequence is effectively a monologue by Dora Maar, Picasso's lover and the model for Weeping Woman: I do remember being struck by the line 'He might be a genius but he's also a prick'.

I find it challenging to review a collection of poetry, especially one as wide-ranging as this: Nichols interweaves art, landscape, memory and the female experience -- the latter especially in the 'Laughing Woman' series of poems -- and gives voices to subjects and objects as diverse as Ophelia, the Empire State Building and Tracy Emin's Bed. Her snapshots of life are vivid (for instance, a poem about how to cross a road in Delhi) and her evocation of a trip into the interior of Guyana, where she was born, makes me crave an experience I've never had. I think my favourite in this collection, though, is the title track, the shifting tone and perspective of Dora Maar celebrating and bemoaning her fame, and reclaiming her self.

Fulfils the 'Poetry Collection by a Black Woman' prompt for the Reading Women Challenge 2021.