#Binge Reviewing My Previous Reads #Classic fairy tales with Modern Implications

This story is, on first glance, one of his strangest and most disturbing works, but when read in the 21st century, it becomes clear that it was decades, even centuries, ahead of its time—anticipating Freud’s psychoanalysis, Jung’s archetypes, and the postmodern obsession with doppelgängers, simulacra, and the instability of selfhood.

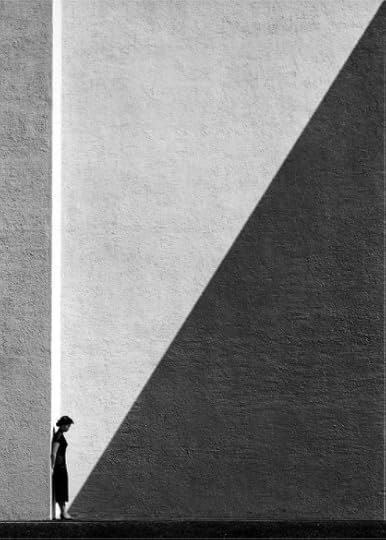

What Andersen presents in this tale is not a moral fable in the usual fairy-tale sense, but rather a philosophical parable about power, identity, and the dissolution of the human into its image.

The story follows a learned man whose shadow detaches itself, grows independent, and eventually returns to dominate its former master. It begins innocently enough: the man lives opposite a mysterious balcony, illuminated by a strange light. His shadow goes exploring while he remains behind. Years later, the shadow reappears, fully fleshed, self-possessed, confident, and worldly.

The master and the shadow reverse roles until, in the climax, the shadow triumphs completely, consigning the man to death.

Already, Andersen was playing with a leitmotif that psychoanalysis would only later codify: the uncanny return of the double. The shadow, traditionally a figure of lack or absence—a mere dark silhouette—becomes here an entity of plenitude, of excess. The man, meanwhile, diminishes into fragility, abstraction, and finally obliteration. In this sense, The Shadow stages what modern theorists would call the “revenge of the simulacrum”: the copy not only replaces the original but asserts itself as more real, more legitimate, than what it displaces.

For 21st-century readers, the allegory is uncomfortably prescient. In the age of social media, digital avatars, and algorithmically curated personas, who is more real—the fragile human body behind the screen, or the shadow-self performing on Instagram, TikTok, or LinkedIn? Like Andersen’s shadow, these curated projections travel further, command more authority, and eventually threaten to eclipse the vulnerable, embodied self. We have all become the learned man, watching our digital shadows walk away into a world where they flourish without us.

The tale also carries a political resonance that contemporary readers cannot ignore. The learned man is soft, intellectual, and bookish, while his shadow becomes powerful, pragmatic, and ruthless.

The story thus dramatises a reversal of hierarchies: those who dwell in appearances, manipulation, and spectacle triumph over those who seek truth or knowledge. It is the logic of the 21st-century media ecosystem: perception is power, not reality. To govern, one must be a shadow, not a man.

Andersen’s ending is chilling because it offers no redemption, no balancing of forces. Unlike in “The Ugly Duckling” or “The Little Mermaid”, there is no cathartic transformation, no transcendence. Instead, there is only annihilation: the learned man dies, and the shadow lives on. This stark refusal of moral consolation makes The Shadow radically modern.

It does not instruct us how to live, but rather warns us that the structures of identity are unstable, porous, and always already under siege.

The uncanny effect lies also in its linguistic and narrative strategy. Andersen destabilises the reader by never fully clarifying whether the shadow is supernatural or psychological, allegorical or literal. This ambiguity — is the shadow “really” independent, or is it the man’s madness? — makes the story an early exemplar of literary modernism, or even postmodernism. Its slipperiness forces the reader into complicity, to oscillate between believing and doubting.

For modern readers, The Shadow becomes less a fairy tale than a mirror. It reflects the fragility of subjectivity in a world of proliferating images and doubles. It reminds us that our shadows — our avatars, our projections, our unconscious desires — are not passive. They watch us, learn from us, and may one day claim our place.

Thus, Andersen’s strange, unsettling tale can be read as prophecy: in a century dominated by shadows that walk and talk more convincingly than their human originals, it is not the man but the shadow who survives.

And perhaps the true horror of The Shadow is not its fantasy, but its accuracy.