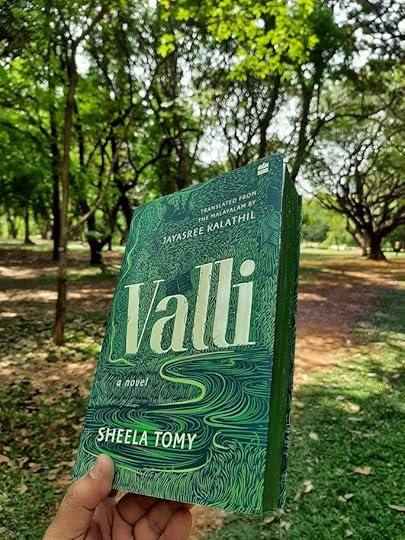

5☆ — as i finished this novel i found it extremely difficult to summarise how i felt while reading it; so many emotions and thoughts, all bursting and tinted with the mist and green of the forests in kalluvayal, the setting where most of the story takes place. i cannot emphasise how important this book is, even as adivasi communities continue to suffer in wayanad and across india for wanting to protect their land from capitalist greed and exploitation which disregard the ecosystem and the people who live in it.

thommichan and sara are a young, hopeful couple who elope together to kalluvayal, where they meet and interact with a host of colourful characters within the lush, verdant landscape. all of this is narrated by susan (thommichan and sara's daughter) in a diary preserved for her own daughter, tessa. if you're looking for a plot, then look away because this book isn't going to give you one- it simply does what literary fiction does best, with explorations of complex characters and themes.

an important theme is relating to the dynamic between the oppressor and the oppressed, within the context of the adivasis and the jenmis (or the landlords). we see how what is violence and what isn't is dictated by those in power, how the media is twisted to comply with the narrative of the ruling class. we see how the oppressor inflicts cruelties and is shocked when that isn't met with grace: they're shocked when the adivasis react with protests when the latter aren't paid as promised, and we see how they're shocked when the people of a land protest deforestation and environment degradation. is poverty, deforestation, and cultural hegemony not violence too?

another important theme lies in the close relationship between the land and the women, both being explored as sites of violence, exploitation, and resistance. they two are also explored in relation to displacement and erasure of identity: the kabani (a river that is an important landmark in the area) dries up from rapid urbanisation, while sara is banished and forgotten from her home town due to her elopement. susan goes to a completely different country for work, and finds that the idols in the shrines of kalluvayal still call for her, except she cannot go back immediately because her life trajectory took her elsewhere. meanwhile, the culture of kalluvayal is rich, but suffers from being overshadowed by the dominant, mainstream language and practices that threaten to completely replace it.

there is an intimacy in the co-existence with the land that the adivasi people here possess:

"Basavan did not understand what his son told him about the government looking after the forest. His son was studying about the forest. But how could he do that far away in town? Should he not be in the forest to learn about the forest? Basavan knew all about the forest, when each tree unfurled its leaves, when it flowered, when it shed its leaves, where the birds nested and which nest belonged to which bird, when they brooded their eggs, which ones roosted in the westering light and which ones took off to catch the worm, which ones went on long flights across the world. He knew where the elephant trails were, and the tiger dens, the names of the creatures that lived in the rivers, the time when fish spawned, the whirlpools in the waters and the crocodile nests. What more was there to learn about the forest!"

a criticism of academia lurks within the prose too. who really are the experts on a land? who deserves to be seen as one? who decides that? the forests of kalluvayal is of interest to researchers in studies relating to culture and history, and they come to take and take and take, upon which they leave and them become self-styled experts on the subject. but what kind of knowledge is that?

this story is also a collection of love stories. the love between thommichan and sara, between basavan and rukku, between peter and lucy, between james and susan, and so on. it's also a love letter to a land, a land that all these characters care for, weep for, and rest on the pulse of.

the prose was abundant and lyrical. there were careful, loving descriptions of the flora, which felt like the meticulous brushstrokes of a painter painstakingly attempting to ensure that you can see his vision because he loves it so; makes sense, since sheela tomy herself is from wayanad and her love for it shows in her work. i would suggest that for anyone who doesn't understand malayalam, it would be best to keep google open nearby because there are many words and terms that are preserved in the original language. it feels deliberate, as the words themselves become important in becoming grounded in the story.

one of my favourite reads of this year, my heart overflowed, broke, and mended itself many times over.