What do you think?

Rate this book

96 pages, Hardcover

First published January 1, 1956

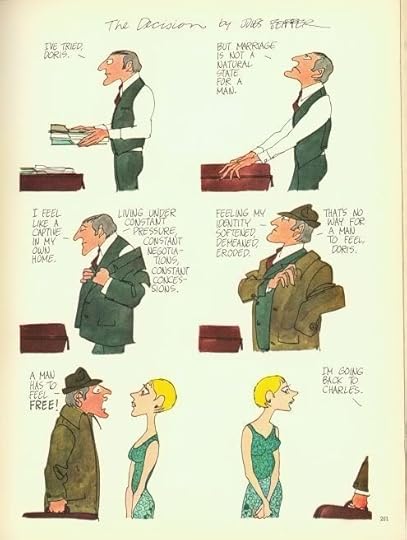

Baby boomers had a habit of falling in love with satirists a few years older than themselves who disliked the counter-culture. When Woody Allen poked fun at “Just Like a Woman” in Annie Hall his audience forgot they loved Bob Dylan for a few moments. Robert Crumb preferred quiet blues to rock n’ roll though he is most famous for his cover of Big Brother and the Holding Company’s Cheap Thrills. Jules Feiffer was of a similar make, but his satire went well beyond a dislike for Dylan. He was deeply critical of the sexual revolution well before it began in strips he wrote for the Village Voice in ’50s and, when it was well underway, in his screenplay for Mike Nichols’s Carnal Knowledge (1971). He spent more energy attacking his white liberal neighbors for their complacency during the civil rights movement than Southern bigots for their brutality. He was terrified of the bomb. Stanley Kubrick in Dr. Strangelove saved his cruelest jokes for George C. Scott’s psychopathic General Buck Turgidson or Peter Sellars’s neutered president. But Feiffer, in his comic story “Boom!” (1959), focused as much on a populace that was disturbingly complicit in ensuring its own nuclear annihilation as on the demons with power. (Paul Morton, bookslut)

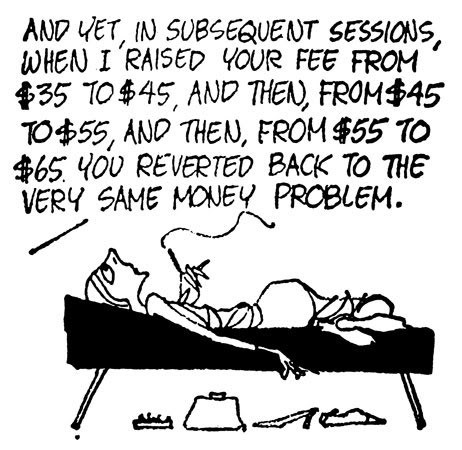

“The Lonely Machine” was published in Playboy. But you were so against everything that Hugh Hefner stood for in that magazine.

Well, apparently. But Hefner was terrific about it. [He didn’t:] try to shape me to the demands of his publication as every publication except for the Voice generally did. Whether you were working for Esquire or Harper’s or the Atlantic or the New Yorker they wanted you to be like them, with their sensibility. Hefner, when he sent me back notes, he sent me back richly-detailed notes, panel-by-panel breakdowns of what he liked and what he didn’t like. And it was never to change my point-of-view to his or to the magazine’s. But it was to make my argument stronger by strengthening what he thought was a weakness. And in many cases he was right.