This 1821 memoir regularly receives citation as a contributor to the allure of Gothic literature. If Walpole, Radcliffe and Matthew Lewis had lit a fire of desire for adventure through spooky places and distant times, Confessions of an English Opium-Eater fanned the flames.

Though written supposedly to warn readers of the dangerous effects of opium, De Quincey instead becomes a tour guide through his fantastical drug-induced dreams. Incidentally, the dreams are described more as exciting wonders of the imagination than any “Just Say No” ad campaign.

“I seemed every night to descend…into vast Gothic halls, peopled with terrible beings,” he writes. There’s a terrifying/tantalizing sense of infinity and entrapment among these antique hallways and otherworldly monsters. At one point he travels back to ancient Egyptian times and experiences life as a mummy:

“I was buried, for a thousand years, in stone coffins, with mummies and sphinxes, in narrow chambers at the heart of eternal pyramids.”

Such depictions of isolation and alive burial will recall another great author, and De Quincey’s contemporary, Edgar Allan Poe. Though known for his brutal and unforgiving literary critiques, Poe found kinship in De Quincey’s “style” and praised his “genius” ability to write in a way “not to be analysed, but felt.”

Certainly we can imagine how De Quincey’s dreams might have sparked imagination in Poe’s mind, and helped him discover themes of suffocation and claustrophobia so common in his greatest stories. If nothing else, the memoir probably encouraged all kinds of writers to start taking opium. Lewis Carroll, perhaps?

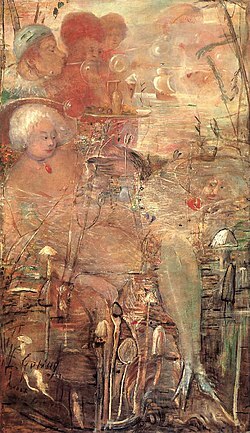

In another hazy fantasy, De Quincey passes by exotic creatures like monkeys, parrots and cockatoos before being transported into “secret rooms.” Here he is both “worshipped” and “sacrificed” during an hallucination of polar opposites, that of a god and sacrificial calf.

Past acquaintances also haunt his dreams. This includes Ann, the young prostitute who had bought him a bite to eat many years ago. Despite her own extreme poverty, she was generous during his time of great need. In his opium high, De Quincey becomes tormented by his inability to return the favor: “She fled away from me — and I followed her in vain.”

In the introduction, the book assures us the content will terrify readers away from opium. For the sake of research, however, it includes sections both on the drug’s “pleasures” and “pains.” Even more ironically, it is the “pains” section which include the most thrilling descriptions. While certainly some dream-adventures can be interpreted as scary, there’s no argument to suggest lasting mental damage or actual downfall to experiencing these wonders of the imagination. If anything, De Quincey makes opium sound like an affordable way to achieve ultimate escapism from dirty, disease-ridden London.

It’s all too obvious how the book’s anti-drug stance is designed merely to appease the “delicate and honourable reserve” of polite society. The 1820s weren’t edgy enough to welcome a new memoir about the awesomeness of opium. So instead we get this book, which basically says “Don’t do drugs because you’ll have too much fun!”

Contemporaries largely saw through the marketing ploy. Nevertheless, it gave critics—who were probably doing opium themselves—a chance to also have it both ways. “The danger of such a book lies in its enchantment. It may teach the young to dream, but not to dread,” wrote one critic in The Examiner.

The Edinburgh Review, mixed with vague concern over the subject matter, offered this bit of praise: “It is impossible to read these pages without being fascinated by the rich, grave music of the prose.”

William Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine—an all-important periodical in the space of Gothic literature—offered the most unapologetic rave with this blurb-worthy quote: “Mr. De Quincey’s pen is dipped in the most vivid colors of the imagination.”

It’s easy to imagine how an 1821 audience would feel enraptured by the sublime images and titillating anxiety captured in this book. But how well does it hold up now?

For me, the prose is of the best variety of 19th century pomp. Sentences are hyperbolically excessive in that high society tone we think of when we envision this era of British literature. This means the prose can get complicated, but it doesn’t take long to settle into the rhythm. Reading it now only adds to the experience of ethereal ambiguity because the language itself is an instant transportation back in time.

The dream sequences are described with unfortunate brevity. Unlike other sections, where it takes multiple paragraphs to say hardly anything, the dreams are whole universes encapsulated in the slimmest of sentences. Best to read them slowly, to allow the weight of each experience to take hold before going on to the next.

There’s still the risk of making opium sound too attractive. De Quincey offers some awareness of the addictive nature of the drug, but pushes the dream adventure too far. There’s a very real possibility De Quincey simply had an active imagination and found a way to repackage his ordinary dreams—or scraps of incomplete fiction—as something provocative. Maybe this is another case of fiction masquerading as memoir, à la A Million Little Pieces? Either way, Confessions of an English Opium-Eater deserves to be studied as much for its clever marketing as for its influence on Gothic aesthetics.

One of the wildest “modern” interactions with this book is in the form of a film adaptation. In 1962, Vincent Price stars as Gilbert De Quincey, a descendant of Thomas. Gilbert becomes embroiled in the opium-fueled underbelly of Chinatown, where he uncovers a diabolical human trafficking ring smuggling Asian women.

While the film has no real plot connection to its source material, it does find inspiration in the book’s hazy, macabre vibe. Dialogue is sparse, opting more for nightmarish imagery, unnerving sound—or lack thereof—and freakshow horror. It goes more for art than entertainment, which was the right call. Certainly a must-watch film for Vincent Price fans due to its unusuality if nothing else. Less critical for Thomas De Quincey purists, but still an excellent example of how a slim memoir has captured our imagination over the last two hundred years.