Syncopated Rhythms of Mind

David Eagleman, the neuroscientist tells us that through experiments he has determined that we can see that time is not a linear flow. These experiments tell us that we can prove that we see time expand and contract, that the order of things come before or after, depending how we observe them or some interior thought process. Naturally, I say, writers of fiction already knew this. And perhaps someone like Marcel Proust didn’t really need proof, or at least he already had it through his own experiments in time and fiction. Which means we should read more fiction.

Jen Craig’s Wall takes us into the mind of a narrator who lives in England, derives from Australia and practices as an artist. She has returned to suburban Sydney to clear out her father’s house after his death. Her mother already deceased. Time is a largely irrelevant element inside the narrator-character’s mind. The movement of thoughts and ideas has no fixed form. Recreating this non-fixed form is a tricky matter for an author. Inside a narrator-character’s mind is an endless chain of linked thoughts and ideas, recalled events, attitudes to those events and creative processes, experiences, relationships. That last sentence in itself is a guide to how compacted the mind and the unfolding of narrated events can be. It can appear like an endless list. Lists are organising principles too, without them most of us would not get through the ephemera of our days.

Art and life meet in Wall. The experiences we all share, in this case the death of a parent, meets the organising principle of the author as it does when our narrator observes and interprets the immediate task of the clean-up of the house.And of course, the artful repurposing of the house's contents for an exhibition, planned before departure. From early on, we know she is going to manage the entire affair by ordering a series of skip bins to dispose of everything. Her father was a quirky fellow, best understood as a kind of free-thinker whose ideas formed into the kind of beliefs I’d call mad opinions and conspiracies. It’s easy to follow a train of thought and believe it’s right inside your own head if all the available limited data you use proves your thinking at any point. Such ideas exist outside linear time, freely move backwards and forwards, proving anything the organising principle wishes to prove. Such ideas go with the endless collection of materials, we call this hoarding, so the house is a mass of contradictory related bits, resources, stuff. Stuff is that term for the endless matter that flows through our consumable world if not disposed of, perhaps even as we buy and own it.

Perhaps one set of free thoughts, like the father’s, is only one step, one generation away from a work of art, there probably isn’t much difference between a mad conspiratorial fiction and a real fiction, until the concept comes together through its organising principle into an intelligent, relatable narrative. We all share family madness, loss, the need too tie it all together.

Always against ‘the competitors’ he would say who were ‘trying to steal his ideas.

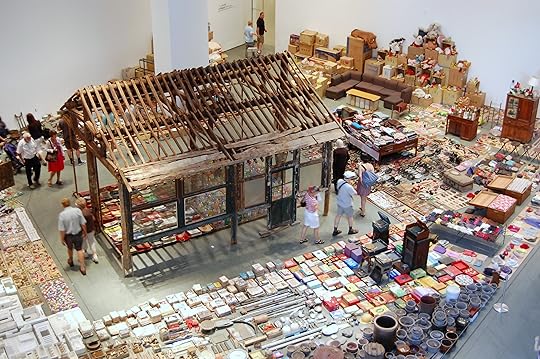

Stuff, also relates to the work of Chinese conceptual artist Song Dong. His mother lived through the communist austerity of the mid-century, the family experienced poverty, privation, persecution, a come down in the world. Her attitude to this was to collect everything – bottle caps, rags, etc – stuff – until the house became a place of despairing isolation, incompatible with living. Song Dong’s response was to turn the house into art, by liberating the stuff from its recesses and displaying it to the world in a new imaginative form.

These interleavings of the stuff that was yet to be sorted. The whole of it: dust, hairs, feathers, books, papers, candles, pins, badges, sticks, leaves, and so all of the bits – all of the usual annoying bits of nothing in particular that had always scuffed around on the floor in my bedroom – wrappings from lollies, as we can call them here, and pen lids. Parts of things that could not be repaired, at least in theory. Always on the point of being sorted of course. I’m just about to sort through that stuff, mum, just leave it will you. Never forgetting the tiniest fragment of any of the matter. This confusion of one thing and another, and their intermediary substances.

Jen Craig’s narrator-character does the same thing. She has been turning her life, an anorexic life, into a conceptual art project for a long time, but the work remains unfinished, still a concept.

Not just conceptual prose, here. The rhythms, language cadence, syntax expertly guide us through a tour of an interior world. It can feel like syncopated music.

This momentously confusing place. This running down of time, of things of thoughts, of existence. This unbearably entropic existence, I was thinking as, with hands and arms now tingling from the scratches got from ripping out those splayed and vindictive plants in the driveway.

Expressly, art in language guides us through all this. As the narrator says of the matter left behind by her father, the shell of a 1980s tv for instance,

Not so much the obsession with the accumulation of objects, then, but rather with everything those objects connected to - everything they held between them and which joined them together. The remnants of my father's projects. All of his unfinished projects - his manifold theories - the haze of his ideas. Not the objects but the theories...

This new book was a tougher read than Panthers.

__________________

Postscript: Wall in the title refers to a work in progress by the artist based on her clearing of the family home after the father's death. But strangely it reminded me of John Coltrane's Wall of Sound ("sheets" not wall in fact thanks to Ian's correction) musical Jazz output during an experimental period. The narrative here might fit, it's a kind of Wall of Narrative Voice, physically on the page, there is little white space from sentence endings, dialogue, paragraphs, etc, only one break, and a part 2. The pages are justified, so it looks like a Wall of Words. Nicely tied in there with Jazz, given the rhythms of the voicing feel a little like syncopated jazz.