not the shahdow of God

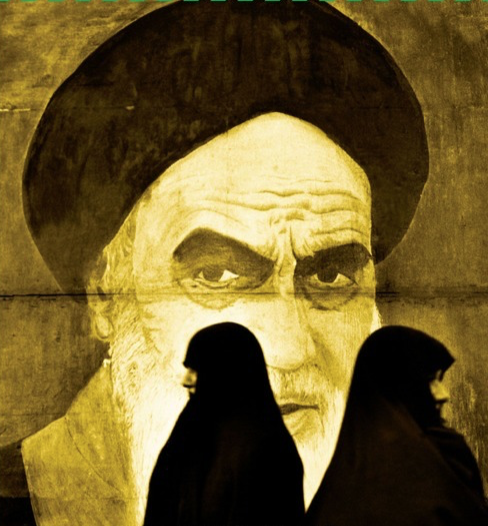

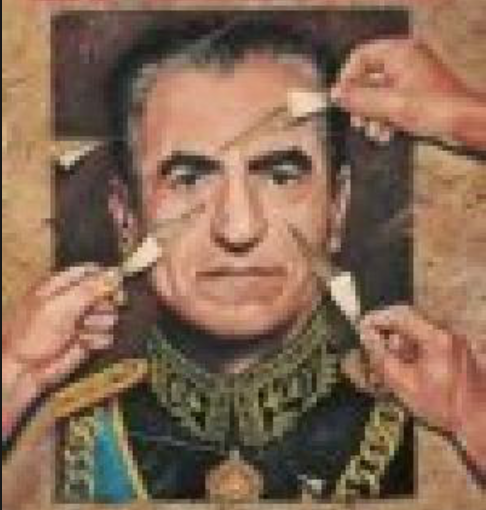

Ryszard Kapusciński was a great Polish journalist who covered, by his own count, 27 revolutions in the Third World (as it was called back in the day). He also wrote about the Soccer War in Central America and later, about the collapsed Soviet system. Whether he was a master of historical facts and cultural knowledge about each of the countries he wrote about is another question. I would not read this book, for example, to know about Iran and its history. I feel he gives it short shrift in some ways. Recently I’ve read “Under Five Shahs”, a self-aggrandizing autobiography by an Iranian upper-class soldier’s soldier for whom discipline and serving the “boss” was everything. There was no mention of torture, massacre, or censorship, not a single word of criticism or doubt. I read “The Persians”, a long, detailed history of Persia/Iran’s bloody history of opposition between ruler and the ruled. That book, by Homa Katouzian, managed, in a most verbose fashion, to show why M. Reza Shah was overthrown in a bloody revolution and why it was the Islamists who came to power after that. But neither of these books reveal in such dramatic and direct fashion the nature of a regime that relied on the secret police and the army to dominate Iran for many years. Kapusciński nails the fear, cruelty, and numbness that underlie such a regime. He uses the idea of “photographs” and “interviews” with Iranians real or imaginary, it doesn’t matter. He creates the dark atmosphere of the times and relies on revealing the psychology of people in Tehran. He does this so excellently, I would argue, because he came from Poland, a country still under Soviet control in the early 80s, a place where, if things were not as bad as in Iran, people kept quiet, suspected everything, trusted nothing. He may not have mentioned Poland or the USSR because he wanted to keep his job, but no doubt his narrative has two edges. In Iran, the Shah sat atop a corrupt system which reflected 2,500 years of Persian history in that there was no rule of law and the Shah controlled all life and property. Though he may have tried to modernize his country, he could not do it by fiat, he could not control the “controllers”, he remained indebted to the CIA.

In short, this is a book about the psychology of people under dictatorship, of people going through a complex revolution, when “eat or be eaten” was a common predicament. A statement which may give you the direction the author wants to take: “…any dictatorship appeals to the lowest instinct of the governed: fear, aggressiveness towards one’s neighbors, bootlicking. Terror most effectively excites such instincts…” (p.115) If you ever liked Garcia-Marquez’ “The Autumn of the Patriarch”, you will definitely like this non-fiction version of a similar topic. Short, but great.