Imagine a vegetable that tastes pretty good (maybe you can do this, I can't). You eat this pretty-good-tasting vegetable and feel both satisfied and healthy.

Such was my experience reading What Hath God Wrought

(The title comes from Samuel F.B. Morris's famous line which he sent over the telegraph; as author Daniel Howe points out, the line was not in the form of a question).

This is a doorstop of a book, at 860 pages of text. It's part of the well-received Oxford History of the United States, of which I've only read MacPherson's Battle Cry of Freedom. It's a history of the US from 1815 (the battle of New Orleans and the end of the War of 1812) to 1848 (the end of the Mexican-American War).

The book is informative, lucidly written, and briskly paced. Due to its enormous scope, Howe paints with broad strokes. In the first part of the book, Howe argues that this period in America constituted a "communication revolution," which is a thread he never fully develops, choosing instead to pick it up and drop it off at various points. At the end of the book, he states he didn't set out to argue a thesis - which I'd disagree with; he set out to argue, he just failed - but rather he set out to write a narrative. Again, I disagree - this is not a narrative history, in the sense it tells a flowing, forward-moving story. Instead, it is a diverse analysis of various events, people, movements, and inventions. He talks about women, religion, slaves, literature, the theater, medicine, politics, the economy, with a little bit of fighting tossed in here and there. Howe devotes entire chapters to some of these subjects, with the result that there are chronological leaps (hence my contention this is not a narrative; or perhaps it is a series of small narratives). For instance, Howe has a chapter called "The Awakenings of Religion." In this chapter, he talks about revivals, millennial movements, the great preachers, e.g., Lyman Beecher, and the evolution of various religious sects. This calls for a separate timeline than the rest of the book; that is, he'll talk about religion during the presidencies of John Quincy Adams through James Polk, then in the next chapter, you'll be back in the presidency of Adams.

The book is exhausting in its determination to tell of this period of American history from all viewpoints. By which I mean the stories of women and blacks, usually relegated to special college courses, are thoroughly told. But don't worry, if you care about the travails of dead white men, they're all here.

At times, the breadth becomes too much, and you just want the book to focus. For instance, during the chapter on the Mexican War, Howe devotes several paragraphs to the role of women in the war. The brevity of the reference leads one to the assumption there wasn't much of a story to tell, aside from a probably-apochyphal story about a Mexican-War Molly Pitcher. All it does it break the flow of the story and forces Howe to toe the line between being a responsible historian and being politically correct.

The trouble with any book with academic pretensions is that it tends to come untethered from humanity. Howe avoids this pitfall by starting each chapater with vignettes of average people living during these periods, and by quoting freely from diaries. He also does a respectable job of giving thumbnail biographies of the "great" personages of his day. I especially liked his take on James K. Polk, which was quite even-handed. He showed him as one of our hardest working, most efficient presidents (in one term, he acquired more land for the US than any other president, including TJ's Louisiana purchase and Andy Johnson's purhcase of Alaska); but he also described Polk's petty, vindictive side, such as his conniving with southern racist/militia general Gideon Pillow to discredit Winfield Scott.

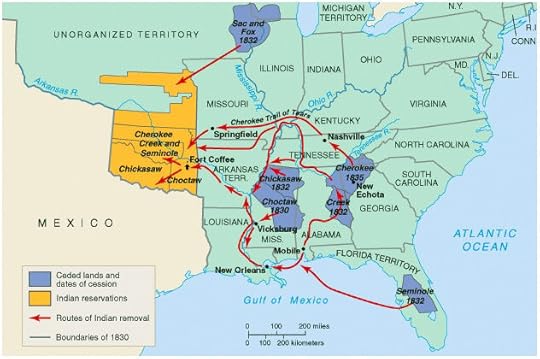

One of the great services of this book is tearing Andrew Jackson down from his pedestal and putting him in the pig pen where he deserves. For whatever reason, it's lately become okay to respect him. I don't understand this. The fact he's on the $20 is an insult. Thankfully, due to the economy, I don't have to look at his ugly, stinking, horse-like face. Howe shows Jackson for what he was: a barely-educated twit; a possible sociopath (the executions of Arbuthnot and Ambrister; his countless duels); a hypocritic adulterer; and an unreconstituted racist. I am convinced Jackson destroyed the Second Bank of the United States because he was too dumb to understand finance. The crowning achievement of Jackson's presidency was the Indian Removal Act, which led to the Cherokee Indians - who had developed white customs, a written language, and started farming, like we told them to - being forced to march to Oklahoma. This was the Trail of Tears. Thousands died. When he left office, Jackson said the greatest danger to America were abolitionists. He appointed Roger Taney, author of Dred Scott v. Sandford, to the Supreme Court. Dear Andy Jackson, thanks for your age of Democracy. Jerk.

Howe also does much to rehabilitate the reputation of John Quincy Adams. Here, Howe goes a bit overboard (he overplays his hand by dedicating the book to JQA). I suppose, though, it's understandable, since Howe wrote a book on the Whigs. John Adam's son was certainly a witty man. When it came to slavery, he called the Constitution a "menstruous rag." Indeed! Howe shrewdly positions JQA, and the Whig party, as the forebears of abolition and women's rights. Indeed, one young Whig named Lincoln went on to do pretty well with the Republican party.

Winfield Scott is also rescued from the dustbin of history and repositioned as perhaps the greatest American general of all time. Howe makes a decent case, though Scott was a Whig so Howe was probably biased. It is interesting, though, that Robert E. Lee, Virginian, who betrayed his country and helped lead an unconstitutional revolt against the Federal Government, is today revered and counted among our heroes, while Winfield Scott, Virginian, who stayed loyal to his country and created the Anaconda Plan that Lincoln used to strangle the South during the Civil War, is mostly forgotten.

The lasting achievement of this book is taking a long, hard, critical look at a mostly forgotten gap in American history. Now, I hope that Oxford will fill in the period between 1848 and 1861.